At Smoke the Moon, two exhibitions of contemporary Indigenous artists consider histories of specific geographies and foster a dialogue countering today’s apocalyptic cynicism.

When The Earth Was Young/REDHORN

August 16–September 22, 2024

Smoke the Moon, Santa Fe

Outside, it was scorching. Peak summer in Santa Fe: another year of record-setting temperatures. My steps zigzagged to dodge fallen plums fermenting on the sidewalks of Canyon Road. Less than a mile away, the Southwest Association for Indian Arts annual Indian Market was winding down its 102nd year.

Throughout the weekend, a constellation of satellite events glimmered with abundance. The gallery spaces at Smoke the Moon feature REDHORN, the latest solo show by Chaz John (Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska/Mississippi Band Choctaw), and When The Earth Was Young, a group exhibition curated by Marcus Xavier Chormicle (Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, second lineal descendant) and Diego Medina (Piro-Manso-Tiwa).

Together, these two exhibitions form a double prism, refracting the lingering white gaze of the market’s ethnographic origins into a full spectrum of Indigenous creativity. Their dual debut during Indian Market fosters a dialogue countering today’s apocalyptic cynicism. Instead, they honor histories shaping our present, offering tangible expressions of endurance and regeneration.

After the weekend, I talked further with John, Chormicle, and Medina to learn more about their respective exhibitions, as well as how timing the opening to align with Indian Market resonated with them as artists and curators.

“The sense of gathering during that weekend and contributing on an individual level to something much larger and more important than any of us cannot be understated,” Chormicle told me.

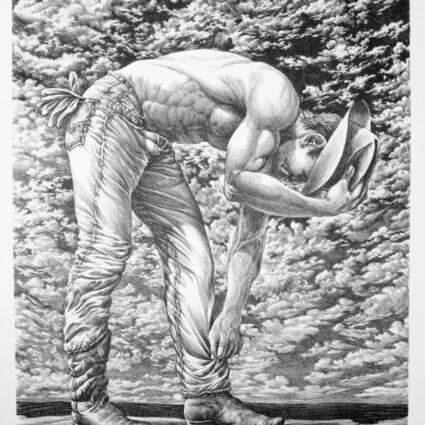

Stepping into REDHORN teleports me to a dimension emerging from Cahokia, the largest pre-Columbian civilization north of Mexico. This ambitious project marks a new evolution in John’s practice, spanning metallurgy, photography, charcoal illustrations, and concrete reliefs.

John began investigating Cahokia’s iconography years ago, but spent the last nine months deeply researching it while producing the works at the Institute for American Indian Arts foundry. “Making the connections between both my tribes in Cahokia was when I knew there was something essential and ancestral in this work that I hadn’t touched on before,” he says.

When The Earth Was Young also marks a milestone for Chormicle and Medina. It is the first show they’ve officially curated together and the first in a space they don’t operate themselves. The show’s array of paintings, photographs, prints, and pottery explore the prospect that the earth and its inhabitants are in their infancy, signaling a vast future yet to come.

“The dross of history can age the perception of a thing,” explains Medina. “The need to historicize reality has left people with a view of the earth as ancient and old, which—while true in simultaneity—negates the reality of the earth being eternally young.”

Nizhonniya Austin (Diné/Tlingit), well-known for her role as Cara Durand in The Curse, presents a trinity of large-scale paintings that assert her studied practice as a visual artist. Her piece Blood! Tears! Electricity! Love! Power! Friendship! (2024) is a dynamic emblem of self-assurance, both comforting and challenging my optics. Soft tones of azure and periwinkle spiral toward a glowing center, punctuated by illusory black and white textures, creating an emphatic exclamation of care that encapsulates the chaotic exuberance of existence.

Hypnotic geometries and earth-toned palettes oscillate throughout Jordan Ann Craig’s (Northern Cheyenne) trio of serigraph prints, transporting the psyche into a dream state. An alum of residencies like Ucross in Wyoming, Roswell Artist-in-Residence Program, and IAIA, Craig meticulously imbues traditional weaving patterns into contemporary printmaking techniques.

Brandon Ortiz’s (Taos Pueblo) micaceous pottery bridges traditional and modern styles, challenging the notion that these categories are distinct. His nine-step process—involving harvesting clay in the mountains around Taos, refining the shapes with sandstone from Ojo Caliente, and sealing cedar-fired pieces with oil—produces an oeuvre that feels both ethereal and terraformed.

Illustrations by Poyomi McDarment (Yokuts) offer a whimsical escape from––or rather, return to reality, blooming with ink, marker, and watercolor depictions of cottontails, ground squirrels, butterflies, snakes, and wildflowers. Her expressive characters gently remind us of the floral and faunal kin we share this planet with—those who came before us and those we have a responsibility to protect.

Jenny Irene Miller’s (Inupiaq) photographs capture a dialectic of grief and resilience. Images recalling “Where our fish camps used to be” (2024) glimpses the haunting aftermath of Typhoon Merbok, which ravaged Alaska Native territory in 2022. Through Miller’s lens, fragments of what’s lost to climate change—manufactured by colonialism—are preserved: a severed oogruk (bearded seal) flipper, eroding riverbanks, melting sea ice. Yet their portraits, like Akłaasiaq (2024) and their mother’s feet sinking into the Nome River, transform sorrow into a vision of revival.

Ambling back through the courtyard, I revisited REDHORN, brimming with questions about how intertwined geographies shape our relationship with time. John delves into celestial events as catalysts, linking an AD 1054 supernova to the Morning Star archetype in Mississippian culture and the Redhorn figure in Winnebago traditions.

Bronze castings of whelk shells, adorned with happy and sad faces made of popcorn and pecans, and phantasmal charcoal renderings of Mississippian effigy pots are all subtly imbued with John’s signature irreverence. A mask crying “LIFE SUCKS” sticks its tongue out beside neo-tribal tattoo designs on a large diptych of stained walnut panels. The bronze castings of sticks and carved whelk shells in front eternalize nature’s fingerprint.

Polaroid snapshots of the shells have an almost ultrasound visual quality to them, leaving me with premonitions of a forthcoming rebirth. The recurring “laugh now, cry later” motifs embody a sense of radical acceptance. By integrating a semiotics of widely appropriated tribal tattoos into carvings, John hints at a deeper, personal reclamation of Cahokia’s history from imperialist patterns of disembodied excavation.

In a world overshadowed by fears of societal collapse, Indian Market weekend poses a clear alternative: Indigenous people are still here, actively shaping our collective future. At Smoke the Moon, this message is amplified by REDHORN and When The Earth Was Young, directing us away from apocalyptic fatalism toward an embrace of iterative creation. Where we come from and where we’re headed may be uncertain, but perhaps that’s not a bad thing.

“I think that’s good sometimes,” says John. “I don’t think we need to know everything.”