Sofie Hecht discusses her project Downwind, a documentary photo album exploring the continued impact of radiation exposure on resident New Mexicans after the 1945 nuclear bomb Trinity Test.

Sofie Hecht (she/they) shows me a photograph of two women with graying hair. Despite their brightly colored clothes, illuminated by the sunlight streaming from some window beyond the frame, shadows pervade and darken the scene. Their eyes are fixated on a blurred smudge of a girl in the foreground, who’s wiping her nose or caught in some playful exuberance. Pink, rose, and lavender hues code the space with feminine development, from girlhood to great-grandmotherhood.

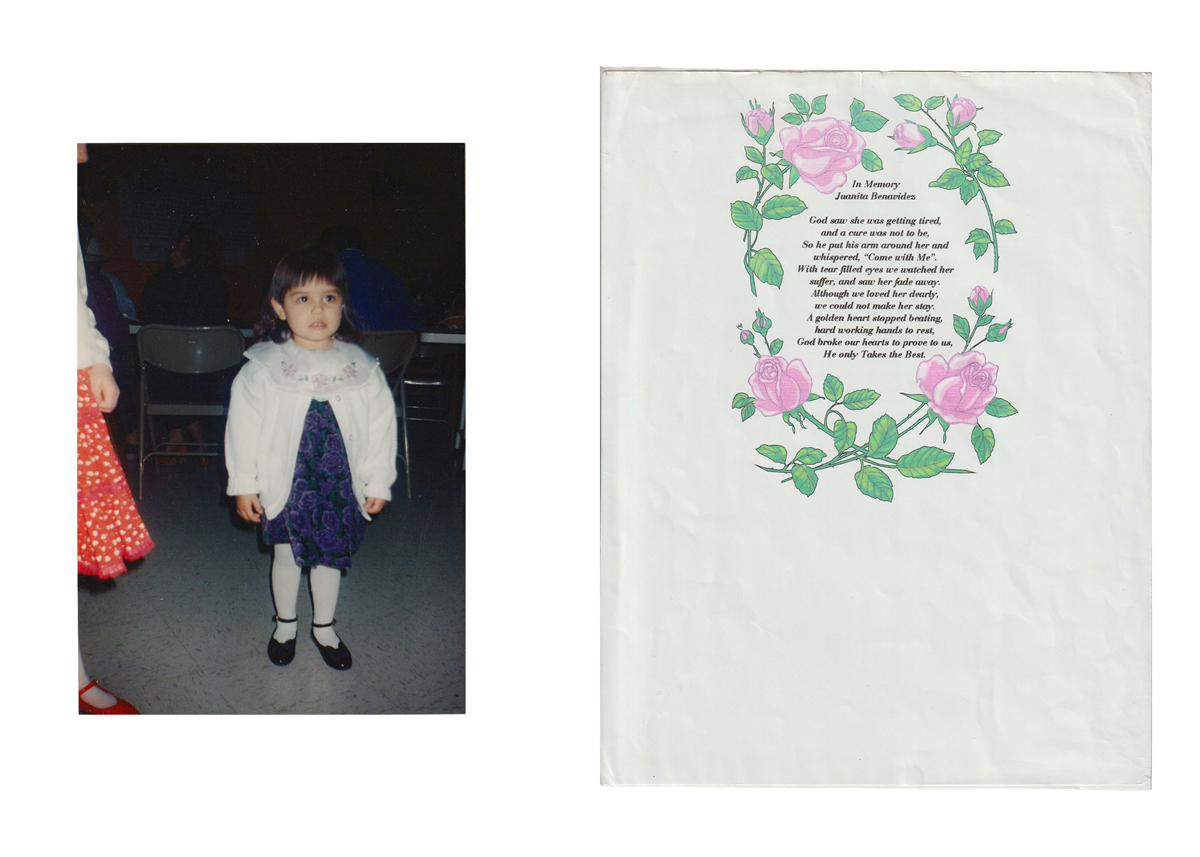

What lies ahead for her? (2023), the title of the piece, poses a question that the women in the image, Josephine Duran and her niece Doris Walters, clearly ask with their eyes as they regard Duran’s great-granddaughter. Ninety-two years ago, the room they occupied in Tularosa, New Mexico, was the scene of the birth of Lucy—Duran’s sister and Walters’s mother. While Lucy survived mild skin cancer, her mother, Juanita, died of bone cancer in 1994. Evarista, her grandmother, died of breast cancer in 1948.

Cancer has plagued many in this family, including Duran and Walters, who attribute this prevalence to the July 16, 1945, atomic bomb test, known as Trinity, detonated fifty miles from their home.

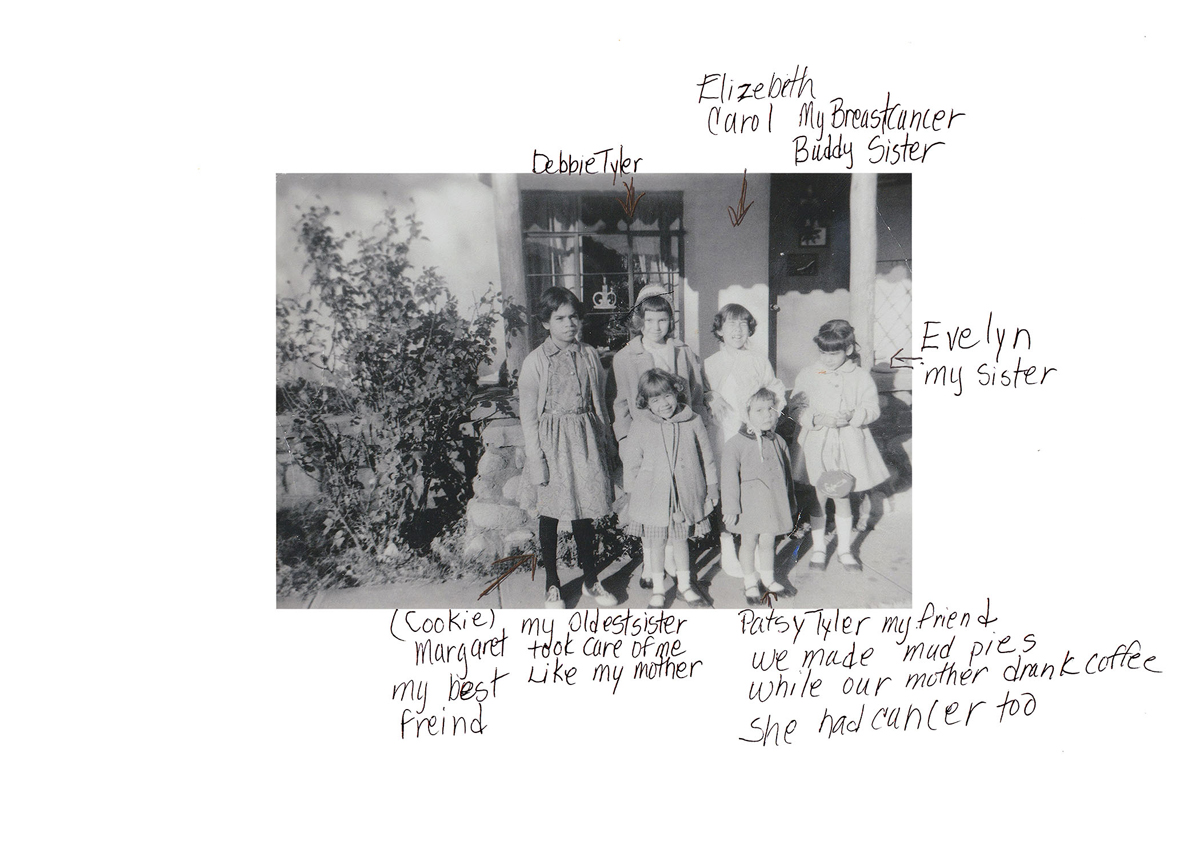

Through an archive of memorabilia and family photographs taken by Hecht and from the albums of her subjects, Hecht’s Downwind (2023-ongoing), a working title, is a still-image documentary of the impact of Trinity on over twenty different families who have continuously resided within a fifty-mile radius of radiation exposure from the nuclear blast that took place nearly seventy-nine years ago. Hecht shows me a collection of time-worn images, including black-and-white photographs of a mother and child, pocked with circles and cracks where the image bleaches into white, and a group of four women in 1950s dresses. The photograph of the women appears to crease and separate the group, with the women on the righthand side fading into an unpigmented abyss.

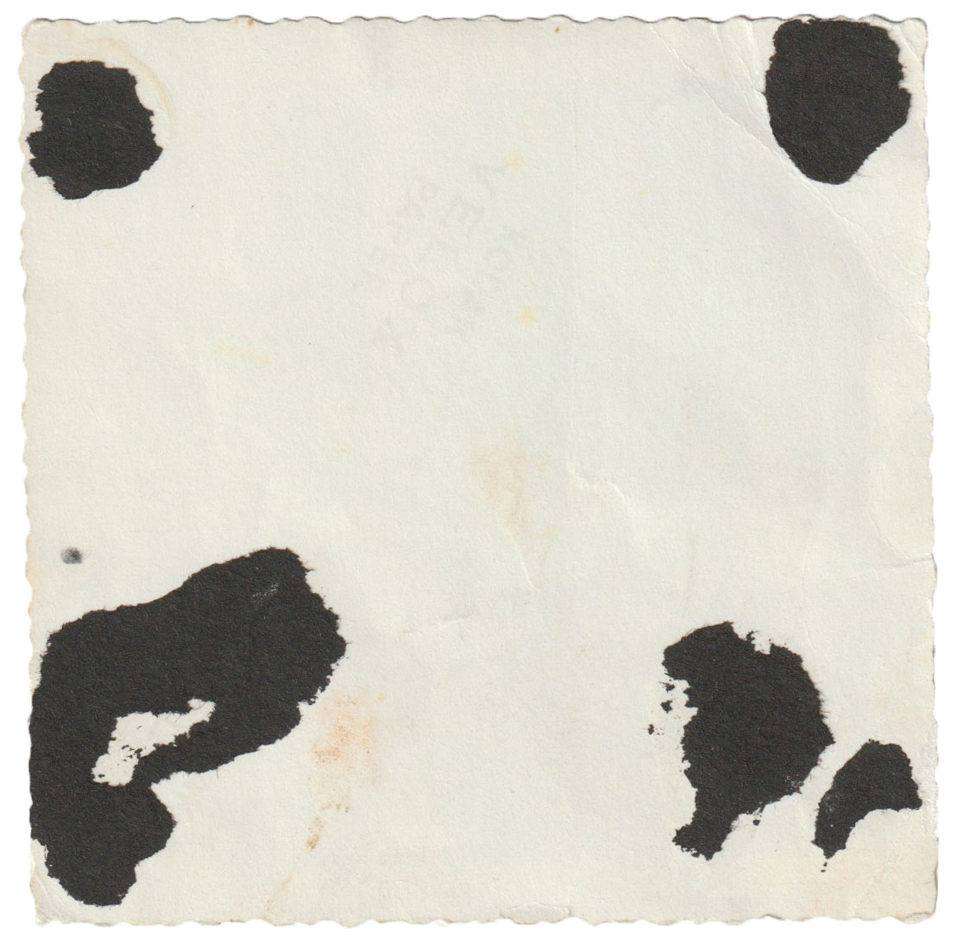

Hecht also shows me an image she captured of the back of a photograph—a scallop-edged sheet containing an ominous spread of abstract black blots. “It looks like cancer,” Hecht tells me, elaborating on the visual tropes she wants to draw the viewer’s attention to.

Indeed, Hecht imagines consciously arranging and collaging these images in a book that weaves the optics of this narrative into a coherent whole, underlining historical throughlines that codify the past and future alike with symbols of death. For instance, Hecht shares a piece depicting a framed scene of a sunset over water overlaid with photographs of a young child. To Hecht, this display taken in Ernest Baca’s home in Tularosa feels like a memorialization of his great-nephew even though the child is still alive.

We didn’t meet in Hecht’s studio as we talked because, as a photographer, Hecht’s studio is wherever she carries her camera. I ask her if it is fair to say that the homes she enters are her studio. She hesitates, ”I suppose. The ‘studio’ lives in the relationships and spaces I co-create with the people I’m photographing. There isn’t one singular physical space.”

The gravity of Downwind kept Hecht and me in a tunnel vision even as Hecht deserves acknowledgment for photographically recording Albuquerque’s queer scene, too. Her collaborative project with Louisa Mackenzie, The Queer Family Photobook (2021-ongoing), includes portraits of “queer people [making] alternative family units in Albuquerque.” “[I want to] represent facets of queer life that are euphoric,” Hecht asserts. “[Not all queer people are] sad, depressed, and angsty. [My photographs show our] resilience and power.”

Moving to Albuquerque five years ago from the East Coast, Hecht also got involved in the city’s drag queen shows, going behind the scenes to capture the queens as they intimately costume themselves in hyperbolic unmakings of gender. Or, as Hecht notes, she is interested in “how people prepare to be seen.”

She has also developed a curiosity about the secrets and rumors surrounding the Sandia and the Los Alamos National laboratories. Listening to friends who worked in the labs herald nuclear power as an answer to climate change while other friends criticized the same enterprise for its capitalist extraction, Hecht asked herself, “Why is this so polarizing?” Looking for answers, she connected with Tina Cordova, part of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium, and found herself going to TBDC’s events. Spending a significant amount of time in Tularosa, as well as some time in Carrizozo and Socorro, Downwind developed into Hecht’s seminal work for a certificate in documentary and visual storytelling through the International Center of Photography.

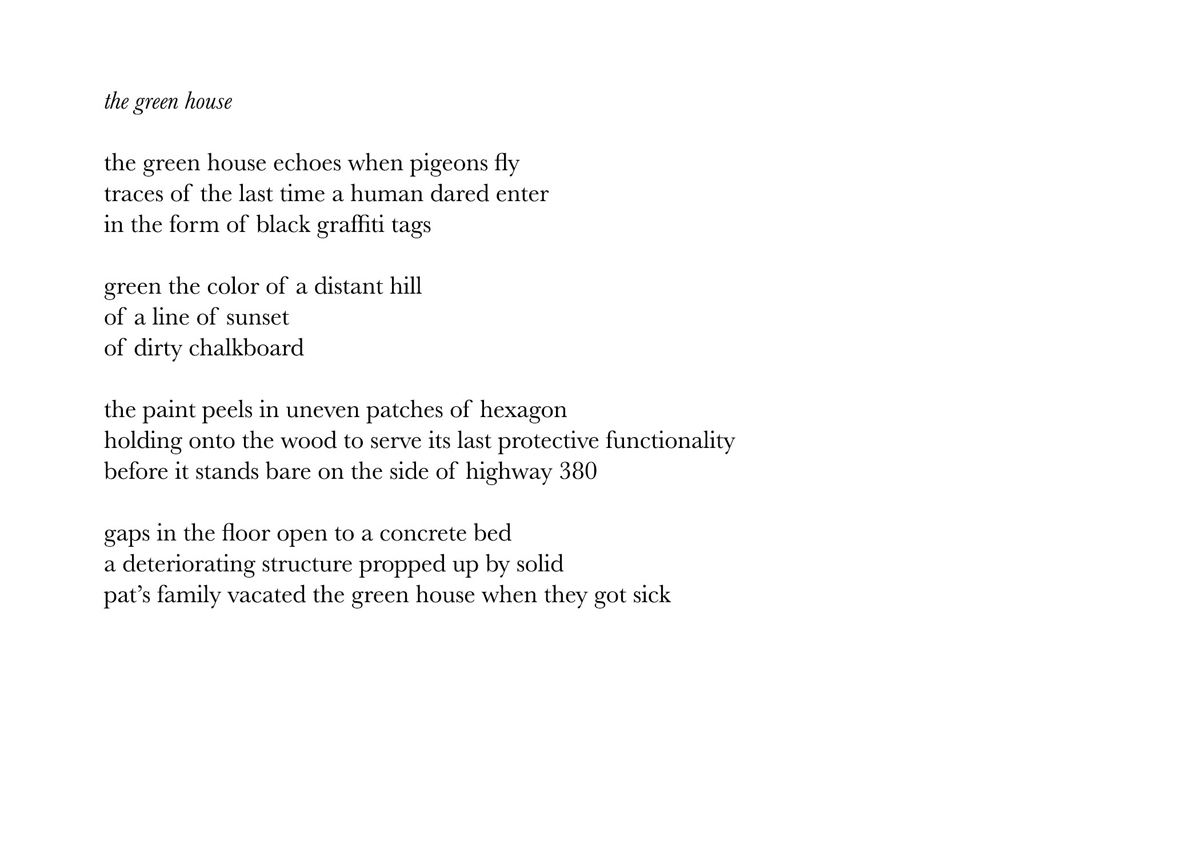

Showing me a photograph of a house with fern green paint flaking off its wood frame like a serpent shedding its skin, Hecht also shares an accompanying poem she wrote with the same title, The green house (2023). The last stanza of the poem contextualizes this site of disowned rot: “gaps in the floor open to a concrete bed / a deteriorating structure propped up by solid / pat’s family vacated the green house when they got sick.” Located a mere thirteen miles from the atomic explosion at Trinity on the side of Highway 380 in Bingham, New Mexico, Hecht recounts the story of Pat Muncy Hinkle’s family, who were never warned nor evacuated before the bomb dropped.

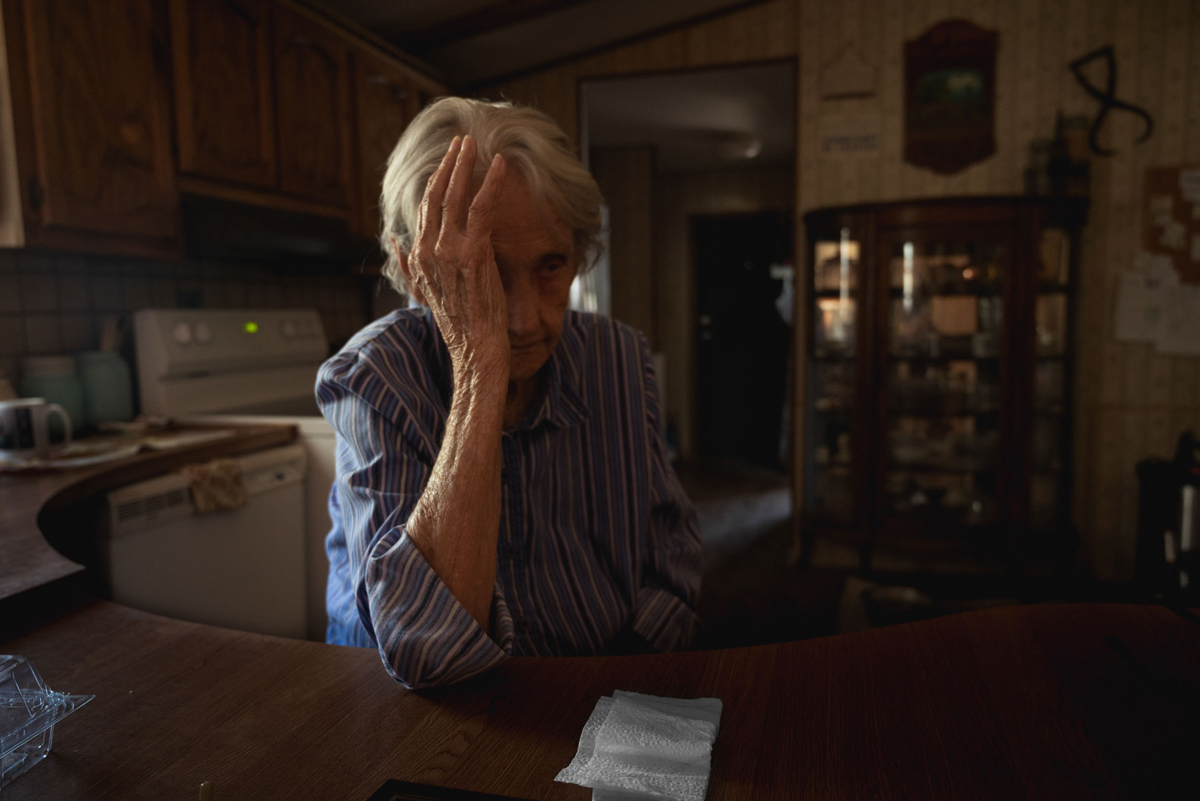

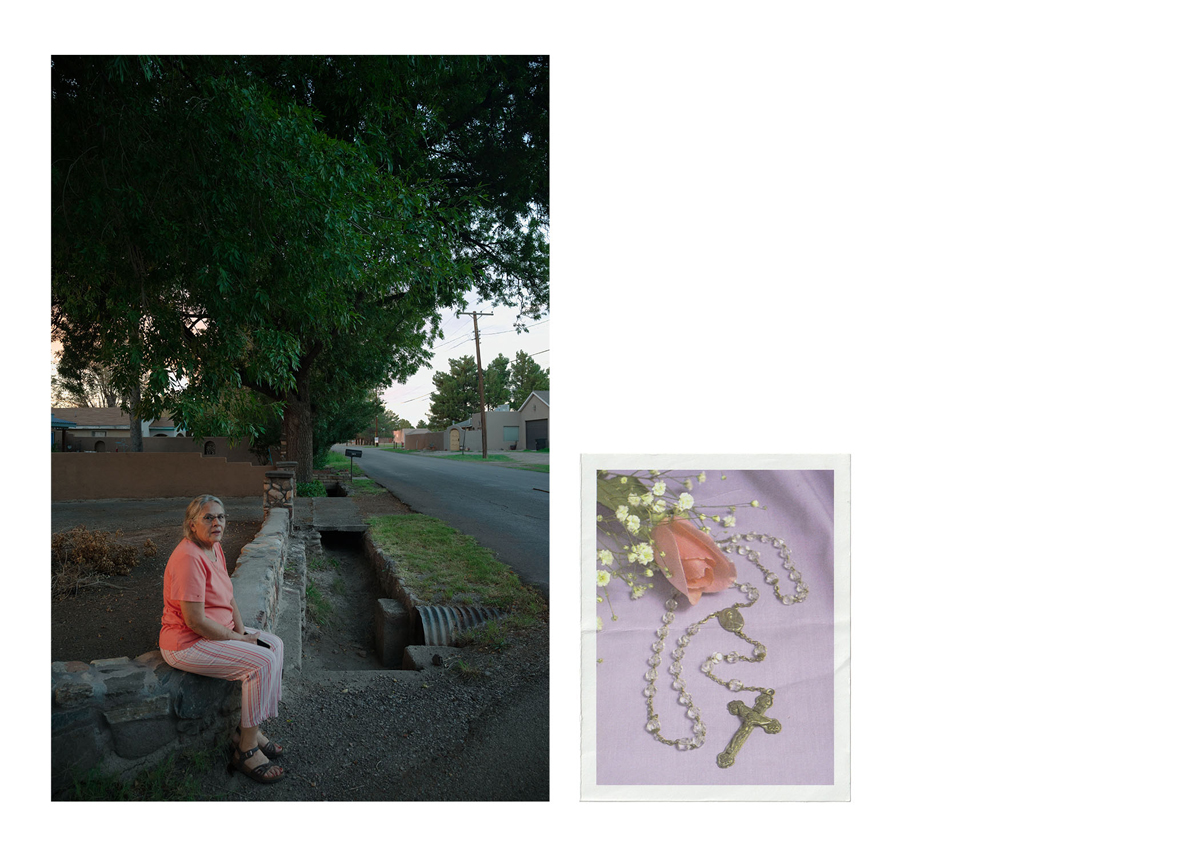

To this end, Hecht highlights a parallel phenomenon of aging and decay. As the remaining bodies affected by Trinity show resilience in old age after overcoming disease, infertility, grief, and loss, the Downwinders’ family archives and abandoned homes show an equal vulnerability to time and exposure to the elements.

Although absent from these images, the story of the susceptibility of Hecht’s own body also becomes part of this chronicle. Hecht describes making Doris Walters (whom she regularly visits in Tularosa) cocktails, sleeping over at her house, drinking water from her tap, and “receiving her love.”

“I’m now in love with these people,” Hecht says. “My body has their trauma, but [their homes are] not my home. I can leave. I have a choice to traumatize and contaminate myself [and become] a product of [their] story.”

The intermingling bodies of the Downwinders and their allies, along with their documentation of themselves, preserve their stories, largely ignored and unacknowledged by the United States government. For these reasons, an anxious sense of exigency undergirds the accounts Hecht has inserted herself into.

In an exhibition proposal Hecht shares with me, she writes: “The Downwinders are currently fighting to be included in the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act before the bill sunsets in June 2024. As the urgency of receiving financial support for an entire community’s suffering only increases, Downwind is a project of preservation amid the precarious landscape of nuclear contamination.” Thus, although documenting an ongoing piece of history, Hecht’s work requires all eyes on it, now. (Since this interview was conducted, the U.S. Senate, on March 7, 2024, passed a standalone bill to reauthorize RECA for an additional five years. Additionally, the legislation would, for the first time, entitle thousands of New Mexicans living near the Trinity test site to receive compensation. The statute moves to the House for a vote.)

Hecht, currently enrolled in the University of New Mexico’s communication and journalism program, finds herself at a crossroads of academia, journalism, and art. Hecht doesn’t see these disciplines in competition, though, stating that her “photography is linked to activism,” supplemented by her academic background. Indeed, Hecht brings a rigorous academic methodology to her art while elevating the aesthetics of her storytelling.

Hecht’s work asks viewers to relinquish preconceptions that beautiful art objects undercut or distract from politics and that all scholarly crusaders for equity must produce aesthetically displeasing empiricisms. The portraits Hecht captures tell complicated and sometimes dreadful stories, mixing feelings of hope and joy with grief and anger. Considering the visual allure of her well-composed images, her artwork only magnifies its complex content and the vexing emotions it invokes.