Etiquette, Santa Fe

October 28 – November 6, 2017

My first visit to Etiquette, for the opening of 8 Photographers at Etiquette in early September, I was shocked. In a warehouse-esque space behind Siler Road I saw, at a single glance, more people under thirty than I have seen in the year and a half since I moved to Santa Fe. Where have you all been hiding? I wanted to ask. Their second show, All That Is Solid Melts Into Air, brings a similar ad hoc exhibition style, rough experimentation, and ambitious range of works, which leaves me convinced that Etiquette’s collective of artists and curators is bringing something new and deeply desired to the Santa Fe art world.

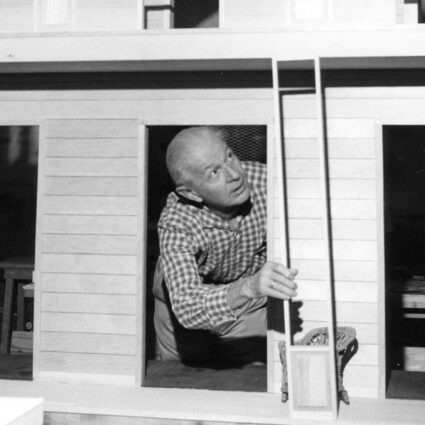

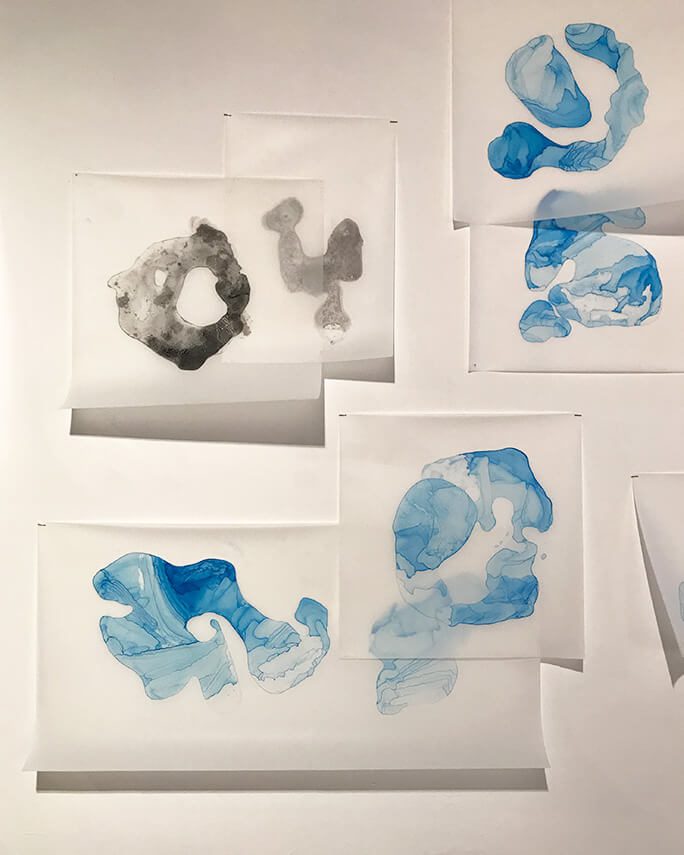

At the center of the gallery, a whiteish, honeycombed felt waterfall tumbles from ceiling to floor, lit by a yellow beam. The effect of Sarah Bradley’s 10-15-17 is eerie but warm, textured. As the felt climbs up and over a small white pedestal, it seems almost alive, a creature. A series of Abigail McNamara watercolors along one wall resembles nothing more than human bones: the arc of a hip, the bowl of a pelvis. There is no wall text in the gallery beyond the artists’ names carved into a six-inch smear of plaster at the front, and there are no titles, materials, or artists listed, which I find dumbfounding. These works remain what I see them as, bluish bone prints.

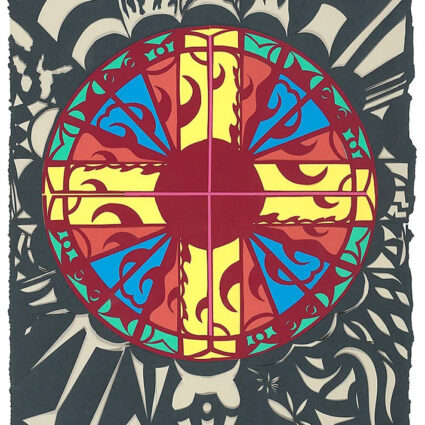

A landscape, a blurred portrait, and a floor sculpture by Nate Masse triangulate in a corner, and because they are installed immediately beside two prints of sky that reference the outdoors, it takes a moment before I realize that the sculpture, Gay Things, and the landscape, Camp Santa Fe, are both composed of smudgy but distinctly human faces. The two adjacent David Gray prints feature text: “AIMLESS WONDER” and “THE MYTH OF FREEDOM.” The style of these prints immediately suggests that they belong on the walls of some avid cyclist’s Airbnb. But to read and think about the text undermines the pseudo-advertisement for the outdoors they seem to imply. Rather than celebrate the human embrace of wilderness, they undermine it. Beside these, C. Alex Clark’s two photographs of fluorescent crystals (the Crystal Consciousness series) frame what appear to be glass sculptures etched with mathematical and cosmological symbols. Ancient carvings merge with holograms, nudging the viewer at the moment she might be thinking the intentions of the work overly serious.

Drew Lenihan, a young curator with a hankering for Frankfurt School theory like I haven’t seen since my first days of graduate school, pointed me toward the Marx and Engels Readers stacked by the door. As he began to explain to me the show’s Marxist underpinnings, I have to apologize for briefly losing consciousness in the same way I always do when a young man explains capitalism to me. But the quote that gives the show its name, one of two passages on the show’s Facebook event page (the only web presence and the only textual documents I have for the show), offers a way in to Lenihan’s thought process. Amid the “constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation” that the show suggests characterize our present moment—though Marx was talking about the 1800s—“relations” between humans and ideas, humans and things, humans and other humans, are no longer fixed but constantly shifting.

My own take on the works in this show is a new environmental or earthly or cosmological mythos and an attempt to understand how the human and the physical environment relate to one another in the context of ongoing ecological threat and damage. Because I am probably always thinking about toxicity, I project my own question onto the works: When the world is toxic to humans, and humans are the cause of that toxicity, how can we relate to—make art about—the physical world? I appreciate that each of these works has a bittersweet feel to it, rather than a celebratory or vitalizing sense of what mythos humans can derive from the earth. In its place, I find a gentleness in these works.