A Greater Utah, a major survey at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, aims to be more representative of regional artmaking than the predecessor show, Utah Biennial: Mondo Utah.

Nearly a decade since the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art in Salt Lake City made waves with the touted Utah Biennial: Mondo Utah, the museum has organized another survey that aims to offer a broader—and arguably more humane—view of the Beehive State, where there’s still little precedence for contemporary art. Titled A Greater Utah, the exhibition will bring together six curators and nearly thirty artists from six different regions.

“It’s hard to define the state of art in Utah because Utah is a place that’s in flux,” says Jared Steffensen, UMOCA’s curator. “It’s a place that’s just starting to realize its history and that’s still creating spaces outside of the conservative majority.”

Steffensen, who was born and raised in Utah, preferred to act as a facilitator for the exhibition, contracting curators across the state who are better embedded in their communities. In contrast, the internationally acclaimed Utah Biennial: Mondo Utah—the first-ever biennial focused on the art landscape in Utah—had accentuated the inherent “weirdness” of Utah, from an almost anthropological approach.

“Most museums do these sorts of exhibitions, but the last time that had been done at UMOCA was under our previous curator, Aaron Moulton, who had spent just a short time in Utah,” says Laura Hurtado, UMOCA’s director. “Of course, one person’s single lens on the state means there are inherent biases and preferences that show up.”

She adds that UMOCA looked to the Getty Museum’s Pacific Standard Time as a reference, but that common curatorial models cannot be replicated in a place like Utah. “There’s [nearly ten million] people in Los Angeles County alone, a relatively small geographic area, whereas in Utah there’s three million people in the entire state,” Hurtado says. “There are real disparate communities that are harder to unify than in places that are more geographically accessible.”

The curators selected for the exhibition include Tiana Birrell from Northern Utah; Peter Everett from Utah County in central-northern Utah; Amy Jorgensen from Sanpete County in central Utah; Jessica Kinsey from Southern Utah; Nancy Rivera from Salt Lake County in Northern Utah; and Valentina Sireech from Eastern Utah.

“I chose to step back from the primary selector role because what interests me in my curatorial practice is the idea of home, or location, but there are various ideas about what that means in various regions,” Steffensen says. “Because of the size of Utah and whatnot, I’m not able to constantly move throughout the state, which means we don’t have much proximity to some smaller communities.”

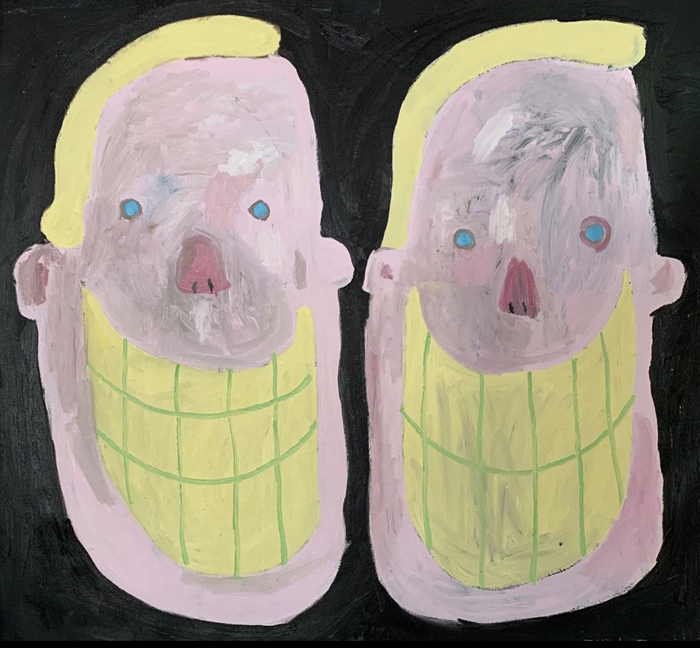

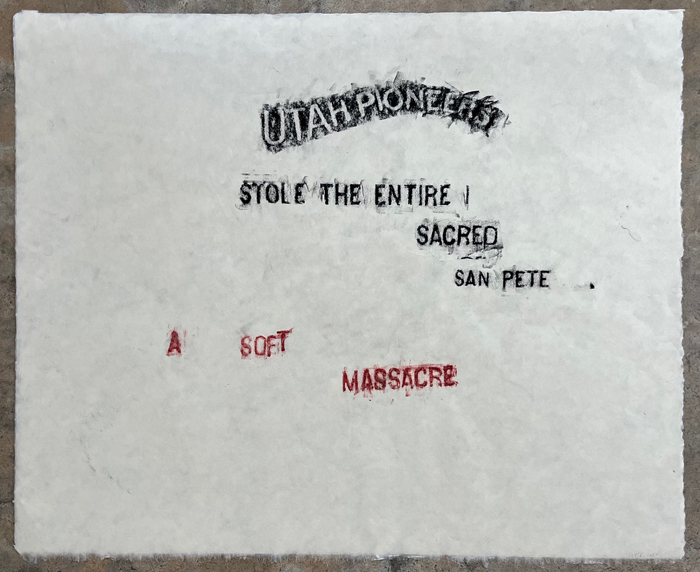

So, what is the state of art in Utah today? The overarching themes in the exhibition are succinctly what one would expect. As a straightforward survey of Utah, the show focuses heavily on ideas around the landscape, religion, and Indigenous histories. The survey considers how the entanglement of all those things has shaped the visual language of Utah, a place defined by beauty and mysticism but also by eccentricity and a despotic church.

For example, queer artist Ray (Rachel) Farmer’s miniature ceramic figures depict fundamentalist Mormon women at work, drawing from the artist’s background as a descendant of polygamist Mormon pioneers and reflecting on the religious mythologies that guide and haunt everyday life in Utah. Nic b. jacobsen’s various works reference Walter de Maria to speak about Mormon settlement. And Katie Hargrave’s and Meredith Laura Lynn’s photographs of Arches National Park consider land rights and the impact of tourism on the natural landscape.

“When we think about art centers, it’s easy to go to the coasts, but there are many artists here making sense of the world around them,” Hurtado says. “We’re on the frontlines of climate change, we’re grappling with our colonial histories, and there’s also a push and pull between love for the land and the reality of the exploitation of the land. You see that depth of investigation and creative criticality throughout the exhibition.”

“Ultimately,” Steffensen adds, “The goal of the exhibition is to amplify voices that have been historically left out of certain conversations—voices that are envisioning a new Utah moving forward.”

A Greater Utah is scheduled to open Friday, July 28, 2023, and remain on view through January 6, 2024, at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art in Salt Lake City.