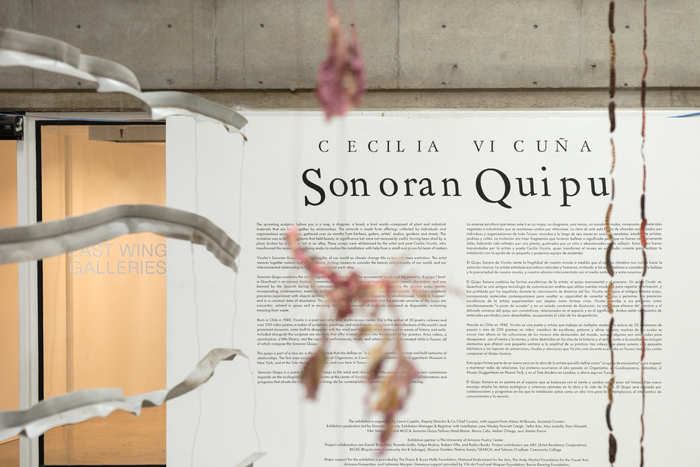

Cecilia Vicuña created the site-specific Sonoran Quipu installation at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tucson with materials shared by community members and through a deeply collaborative process.

TUCSON—A suspended string of seed pods, a metal chain formed into a spiral, a hanging stack of bicycle tires, and a tumbleweed. They’re all part of the expansive sculpture created for Cecilia Vicuña: Sonoran Quipu, an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tucson that opened January 27, 2023, and continues through September 10, 2023.

The exhibition features the artist’s contemporary take on an ancient Andean communication technology called a quipu—in which strings and knots recorded and communicated information—as well as ephemeral sculptural forms the artist calls precarios. Vicuña conceives the quipu as a web of relationships, which helps explain why the exhibition came together through a collaborative process.

The exhibition is organized by Laura Copelin, deputy director and co-chief curator for MOCA Tucson, with support from Alexis Wilkinson, the museum’s assistant curator. But Tucson community members—who answered the museum’s call for contributions of “plant matter and found debris from their surroundings”—also played a significant role in bringing the installation to life.

The museum spent about six months collecting materials, which were stored throughout the labyrinth of its spaces. When Vicuña, who divides her time between New York and Santiago, Chile, arrived to begin the installation process, museum staff transformed the Great Hall that would eventually house the exhibition into a studio for the artist—laying everything out on long tables or the concrete floor, organizing items into categories such as plant stalks or metal.

“Cecilia wasn’t just interested in precious objects like agave stalks; she was also interested in the things we throw away,” recalls Copelin. “The attention she gives them is transformational.”

Vicuña spent just over two weeks in Tucson, working with several members of the museum team and a small group of fellows from Tohono O’odham Community College to create and install the site-specific quipu.

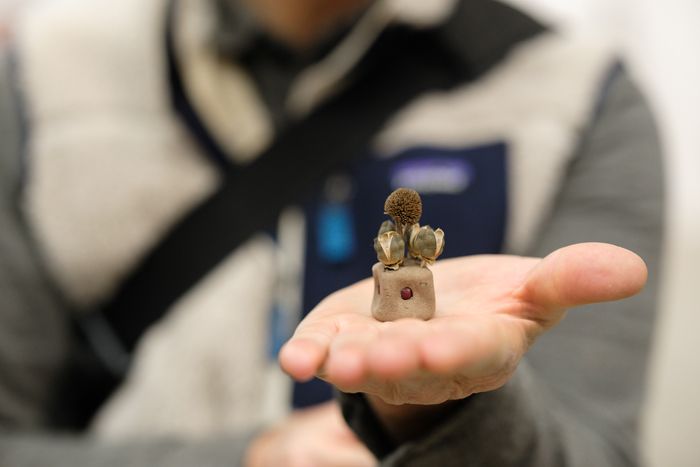

“There was a lot of conversation and collaboration,” says Copelin, who remembers the artist setting seeds inside mud forms she’d harvested from the Santa Cruz River to create small sculptures for each of the participants. “Her intention,” adds Copelin, “was that we all become seed people together.”

Dominic Valencia, exhibition manager and registrar for the museum, had the task of cataloging all the donated materials. Valencia says he was struck by the artist’s nurturing approach, which included calling the items “babies” or “beings” rather than “objects.” Valencia describes Vicuña undertaking minimal intervention rather than manipulating the materials, noting that the artist “accentuated what was already present to bring them to life.”

Wesley Fawcett Creigh also worked alongside Vicuña as part of the installation crew, which fabricated various sculptures and discrete assemblages that would eventually become part of the expansive quipu.

“Cecilia drew out images for us, but also gave us freedom to use our judgement, and she was great about reminding all of us how much she appreciated the care we put into everything,” Creigh recalls. “She has a lot of faith in her vision and in people, so that trust follows.”

Throughout their time together, the crew acquired an illuminating look at Vicuña’s creative process.

“She’s very intuitive about what each element conveys, and about the ways they’re positioned to tell a larger story,” explains Creigh. “In large part, her interpretation of the elements she’s working with is very open, but she’s very interested in the interplay of natural and human-made materials.”

When Copelin looks at Sonoran Quipu now—which centers other exhibition components including three videos, a sound piece, a little library, and something more ethereal that museum materials describe as “the vapors of performances, rituals, and relationships Vicuña created while in Tucson”—the curator remains mindful of its significance and meaning.

“It’s a really important work on a local and global scale,” she says. “It reflects the artist’s longstanding commitment to ecological issues and the organic, intuitive nature of her work.”