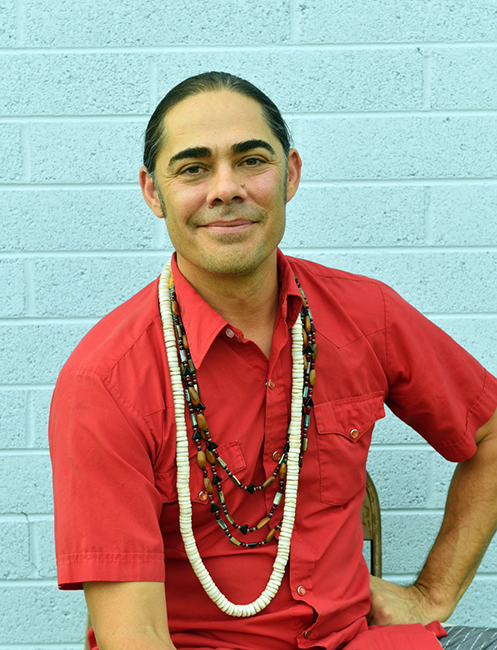

Jacob Meders (Mechoopda/Maidu) works in his Phoenix studio to counter historical and contemporary stereotypes of Native Americans through printmaking that addresses issues related to culture, identity, and place.

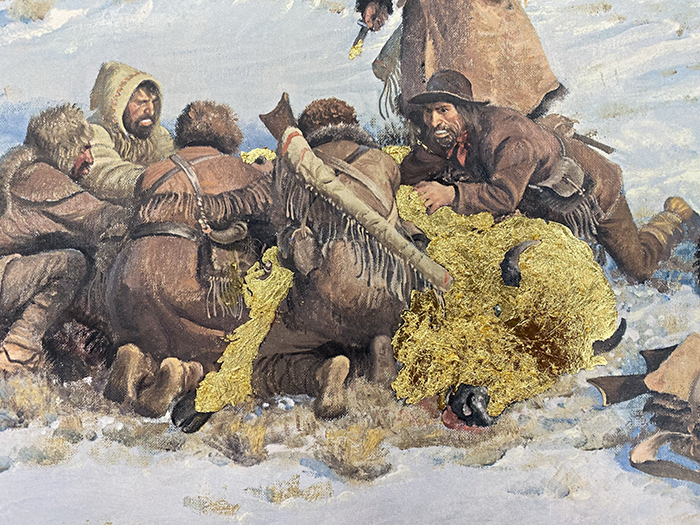

Decommissioned prints from the city’s art collection hang inside Vision Gallery in Chandler, Arizona, where they would have promulgated romanticized white perspectives on Westward expansion and Manifest Destiny if shown before the creative intervention of artist Jacob Meders (Mechoopda/Maidu).

Meders revised the prints for his exhibition Familiar Territory, blacking out figures to signal federal policies designed to erase Indigenous cultures and adding gold leaf to reference resource extraction and the impacts of capitalism on land and water.

“People need to remember whose land they’re on,” says Meders. “These are things to be critical of and art is a great way to have those conversations.”

The exhibition, on display through March 11, 2023, also includes found objects, such as a plate and small bust of a Christian religious figure, modified by the artist to suggest the ways sacred objects are commodified and discarded in Western culture.

“I don’t remember a time when I wasn’t making art,” he says.

As a child, Meders would often draw or carve small objects using a pocket knife. “I felt like art gave me a voice, and I started to realize that I don’t want to make things that are aesthetically pleasing.” Instead, Meders wants his work to help people think differently or change their perspective.

Throughout his practice, Meders counters stereotypes of Native Americans, employing diverse media to critique notions of identity, culture, and place rooted in the assimilation and homogenization of Indigenous peoples.

Sometimes he uses book forms to reflect Western concepts such as the linear nature of time, or appropriates from those who’ve appropriated Indigenous imagery. “It’s not some white man’s story to say who we are.”

Meders works in a large two-story studio that sits behind his home in a quiet Phoenix neighborhood, where he talked with Southwest Contemporary in January 2023 about not only his work, but also his passion for surfing, skateboarding, and customizing the 1950 Ford Sedan and 1964 VW Bug he considers his “war ponies.”

Instead of keeping set studio hours, Meders works around his family’s schedule.

Upstairs there’s a desk used by his wife, Marisa Duarte (Pascua Yaqui/Chicana), whose work explores digital technologies as forms of social resistance. They’re both faculty members at Arizona State University, so the studio is filled with books—but also with the tools and materials Meders uses to create his artworks.

Downstairs, he’s got printing presses, drawers filled with art supplies, an area for various pieces of wood, a computer, and an intriguing array of objects that find their way into various installations, including a wooden cigar store Indian.

Meders works in various mediums, depending on the concepts he’s exploring or ideas he’s trying to convey. Typically, his artworks incorporate various layers of meaning. “I like to leave room for people to come back and look at a piece differently after they’ve learned more.”

For the 2021 solo exhibition And It’s Built on the Sacred at Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art in Arizona, his installation included dirt sourced from the ancestral lands of the Mechoopda people, where the city of Chico, California is located today.

In the 2022 group show Fire and Water at the Gallery at Tempe Center for the Arts, also in Arizona, Meders created an installation with willow gathered by his sister Ali Knight-Meders, which he brought back from one of his frequent road trips to the same California region.

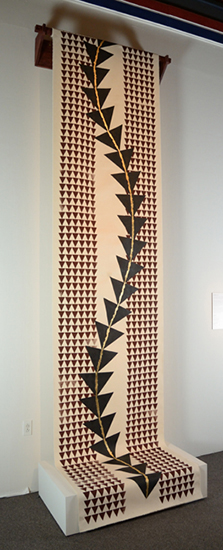

More recently, he’s been making new work for California Stars: Huivaniūs Pütsiv at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe, and Ni Sin Mo’ Meh To Weave Water at RedLine Contemporary Art Center in Denver. The former, which recently opened, is scheduled to hang through February 14, 2024, while the latter is on display from March 11 through April 9, 2023.

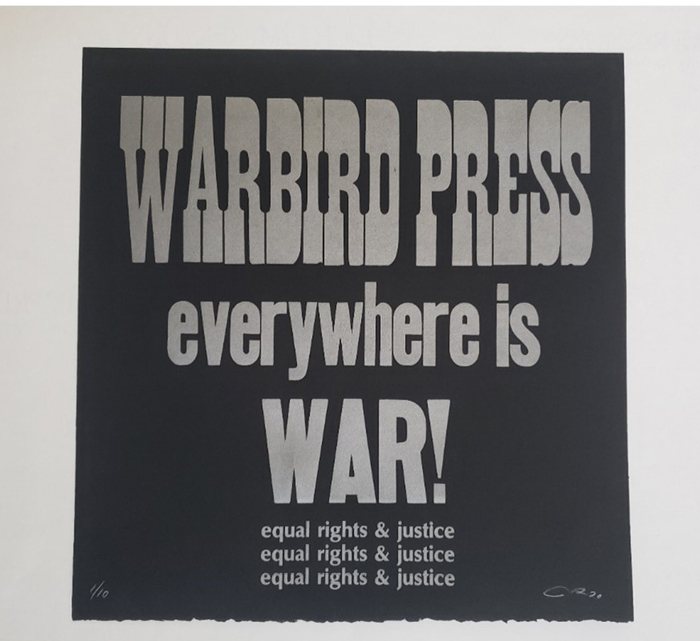

Patterns and symbolism from Mechoopda basketry and weaving appear throughout his body of work, which includes several types of printmaking. “I got into printmaking because I saw how images of Indigenous people were being used in propaganda, and I realized that the power was in the print.”

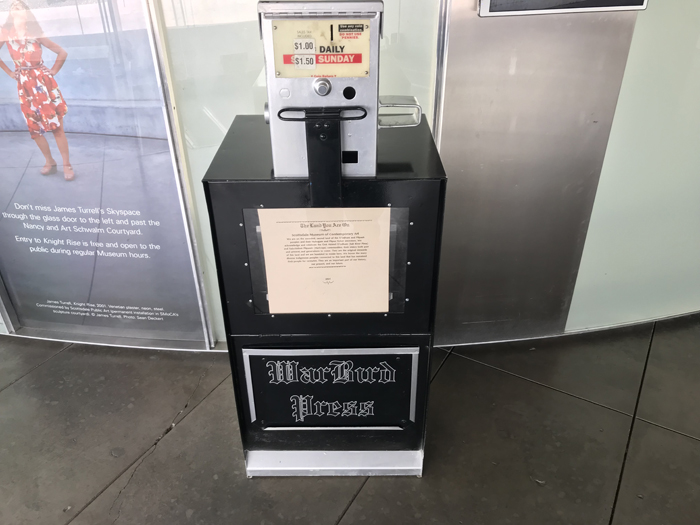

In 2011, Meders founded the Indigenous printmaking studio WarBird Press, which focuses on “producing, sharing, and teaching printmaking with an eye towards Indigenous justice.”

Three years later, he launched a social engagement project for WarBird Press, which includes releasing free or low-cost prints through repurposed newspaper vending machines temporarily installed in public places. “I wanted my work to be accessible to anyone,” Meders says of the project.

Lately, he’s been dreaming of a collaborative project, although he knows it would take significant resources to make it happen.

Meders says he’d love to work with other Indigenous artists on a car that would essentially be a “group show that travels.” It’s an idea inspired in part by the 1985 Chevy El Camino (Maria, 2014) that artist Rose B. Simpson (Santa Clara Pueblo) transformed with designs reflecting traditional Tewa black-on-black pottery.

As his art practice continues to evolve, it’s clear that Meders want to keep expanding his own knowledge, through ceremony, reading, research, and life experiences.

“I’m always trying to find new ways to do this, so I’m not getting stagnant or making work that’s safe.”