María del Mar González-González, a Utah-based curator, bolsters artist voices that are too often relegated to the fringes of discussions about Latinx art.

Utah-based independent curator María del Mar González-González approaches her work with a penchant for community connection. In the process, González-González, a Weber State University art history professor with a specialty in Caribbean and United States Latinx art, provides Utah’s art scene with a soundboard for marginalized voices as well as compelling shows that spark conversation about Latinx experiences. After co-curating the exhibition Vida, Muerte, Justicia at Ogden Contemporary Arts in the fall of 2021, González-González is now preparing for the show Beyond the Margins: An Exploration of Latina Art and Identity, which is scheduled to open on January 20 at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art in downtown Salt Lake City.

Vida, Muerte, Justicia, co-curated alongside Utah artist and curator Jorge Rojas, unfolded in response to Black Lives Matter and its calls for social justice, and featured Latinx artists grappling with systemic injustices, social inequities, and deaths resulting from state violence against people of color. While the OCA exhibition proved successful in its own right—with an array of diverse work from international, national, and local artists—the show’s greatest achievement may well have been in its engagement.

“One of my favorite things was that we did a lot of outreach and interviews in Spanish, and that brought a completely new audience into the space,” González-González says.

A student covering Vida, Muerte, Justicia for WSU’s student newspaper felt a crucial connection with Michael Pribich’s Essential. The piece, an arrangement of work gloves in soft-sculptural rings hung from the ceiling, explores the lack of protection essential workers of color faced during the pandemic.

“Those are the gloves my dad wears to work every day,” the student told the curator. González-González adds, “[The student journalist] is the daughter of immigrants. I still have students writing about the work in that show, believe it or not.”

With hopes of sparking further conversation, González-González continues her curatorial work through a Latin American lens in Beyond the Margins. The forthcoming show at UMOCA, according to the curator, examines “quieter concerns like femininity or ethnic expectations.”

“We’re beyond the margin,” González-González continues. “I feel like women artists—especially Latinas—tend to be marginalized or [relegated] to a footnote.”

In full disclosure, González-González selected my spouse Nancy Rivera’s (Mexican American) work to be in Beyond the Margins. Her photo series Impossible Bouquets: After Jan van Huysum, a depiction of synthetic-flower bouquets that comments on the immediacy of artificial products with layered nuances in its Dutch still-life pastiche, spurred González-González to find work of similar ilk. She will also include works by Frances Gallardo (Puerto Rican), Tamara Kostianovsky (Argentinian American), and Yelaine Rodriguez (AfroDominicanYork).

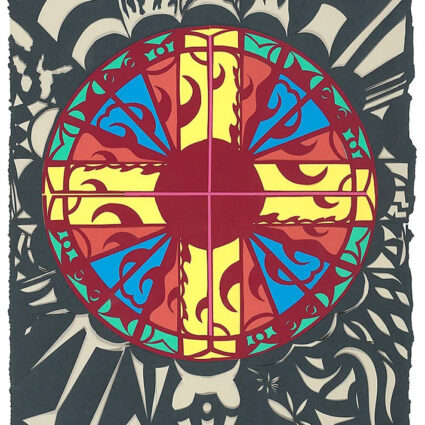

Kostianovsky will show a soft sculpture of a contorted, dead bird, which nods to Dutch still lifes in their own right. The piece Every Color in the Rainbow queries our consumption of fast fashion and, in turn, the exploitation of women and children factory workers. Rodriguez designed the clothing the models wear in her diptych of portraits Saso and Yaissa, which subvert the tradition of European portraiture with images of regal Black people styled as Orishas, paying tribute to Santería and Vodou. Gallardo underscores the paradoxical beauty of hurricane patterns—storms that have rattled Puerto Rico—with a delicate, hand-cut, four-layer paper collage called Carmela. It’s redolent of Caribbean mundillo lacework, lacework from the Dutch Republic, and consequently, the diverse artists’ shared but varied relationships to colonialist trauma.

“We’re going to see how [Gallardo is] playing off these dichotomies and these expectations, and how [what] looks like it might be a very beautiful, craft decorative piece is, indeed, more complex,” explains González-González. “We go back to the conceptual way in which the artists are addressing these topics. They’re a lot more layered.”

In Beyond the Margins, González-González ultimately vies to defy tropes and stereotypes often affixed to Latinx art.

“One of the things I’m interested in is how art collections and museums have framed the way we think about things,” she says. “For example, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City has been pivotal in how, in the United States, we think about Latin American art.” Yet, in popular discourse, MoMA’s colorful hallmarks by Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo may cast Mexican art—and Latin American art at large—with a homogenous aesthetic that doesn’t represent the mosaic of Latinx art, much less that of contemporary working artists.

Looking to demonstrate the diverse practices that comprise Latin American art, González-González also takes inspiration for Beyond the Margins and her current curatorial exigencies from her class lectures. Upon revisiting various Latinx artists pigeonholed as “avant-garde” rather than included within the canon of Latinx art history, she reclaims their positions as bonafide Latinx artists.

“We’ll see that the artists who fall within a more conceptual frame don’t fit within specific stereotypes—or even sometimes within their own groups—[and] are left out,” says González-González.

In addition to the seminal social-practice artists of the Puerto Rican Division of Community Education, she heralds Chicano performance artist collective Asco, Nuyorican artist Raphael Montañez Ortiz, and Colombia’s Óscar Muñoz as conceptual luminaries unbeholden to ethnic-art expectations yet incontrovertibly members of their own cultures. For the past ten years of her career, such art at the fringes has motivated González-González’s exploration of the intersection between art and politics “paired with conversations with my peers about how they would show work in class and be told, ‘Well, that’s not Mexican enough’ or, ‘That’s not Chicano enough’ or, ‘That’s not Dominican enough,’” she says.

“I feel like the fact that a Latina is curating Latinas in Utah is itself a defiant political act,” González-González says. Beyond the Margins centralizes both Latinx artists and audience members through a Spanish-language experience. The show will be fully bilingual, prioritizing Spanish throughout the show. What’s more—with UMOCA’s free entry, downtown location, and relative proximity to Salt Lake City’s under-served Westside, where many Latinx community members live—González-González and UMOCA are treating accessibility as a paramount concern.

“How do I make this show welcoming but, even more important, accessible—and make the audience feel like they’re being engaged with, not just talked down to? I think it’s something that we grapple with a lot—within museums but also within academia. How do you make it so that people feel like, ‘Oh, I get this, and I’m enjoying this?’”

González-González shares one prompt with the Latinx community and other audiences in order to spark further conversation.

“I think one of the things I want them to do is to not come in with preconceptions and stereotypes,” she says. “I want to let the work but also the artists’ words come through and give them that space to share their own voices and perspectives.”

González-González plans to lead two Spanish tours and conversations in February, one of which is scheduled to feature Rivera on February 25. All tours take place Saturday afternoons, and UMOCA has planned an art bash featuring a live band for the opening reception on January 20. Beyond the Margins is scheduled to be on view through March 4, 2023.