Urban Pop in Bountiful, Utah offers a unique opportunity to see big names, but the exhibition fails to situate artists within the movements to which the show claims they belong.

Urban Pop

July 29–September 10, 2022

Bountiful Davis Art Center, Bountiful, Utah

The modest but burgeoning Bountiful Davis Art Center boasts an impressive forty-year history as an art institution that’s thrived in a suburb of Salt Lake City. Since BDAC’s move to Bountiful’s quaint Main Street in 2015, the Center has expanded operations, including critical exhibition programming and community involvement. BDAC has also cultivated relationships with artists across the state and established itself as a cultural institution with merit on its own accord—and not merely by virtue of its proximity to the capital.

Currently, BDAC is hosting the ambitious new exhibition Urban Pop, composed by independent curator Todd Marshall and likely the first of its kind in the region.

The exhibition is a wonderful homage to some beloved local artists, highlighting the talents of artists John Bell, Jared Lindsay Clark, and Matthew Sketch, among others. Their work is paired with international figures like Jasper Johns, Kehinde Wiley, Niki de Saint Phalle, and Peter Max to demonstrate the diversity of style and subject within what Marshall dubs “urban pop art.”

While the exhibition creates a great opportunity for local residents to see work by internationally famous artists as well as local figures, the arrangement suffers from a critical lack of context regarding both how the selected artists work in concert with each other as well as the movements at large.

Exacerbating the problem is the show’s title and concept—the “urban pop art” label that, at its core, masks a theoretical contradiction between Pop Art, which seemingly thrives in an institutional and commercial setting, and street art, which gains its post-modernist credibility from being elusive and anti-capitalist.

One could argue that such contradictions are intrinsic to the street art movement as it exists today—think of Banksy’s role as an art-market darling despite his subversive acts like the 2018 shredding incident. “Urban pop art,” however, feels like a misnomer. Far from being an accepted term within art historical theory, the nomenclature seemingly captures the capitalist trinkets which thrive on online marketplaces like Etsy that enable users to convert their personal photos into a Warhol-esque canvas print or buy a poster of Marilyn Monroe with neck tattoos.

The exhibition comprises the bulk of the main floor gallery, arranged with moveable walls that maximize the colorful and diverse array of selected artworks.

Sketch’s work—often large-scale acrylic paint with gold leaf—utilize popular imagery such as numerical and alphabetical configurations paired with figures like the Monopoly man to slick and formally interesting effect. Sketch’s existence in a lineage of Pop Art is stylistically obvious. Similarly, John Bell places discordant textures and lively colors with art historical figures such as the cherub—here In Bloom (2021)—in formally interesting pairings. The whimsical nature of these works is perhaps the connection to Pop Art, just as Jacob Haupt’s pair of photos Asleep (2017) and Demons (2017) depicts a vintage Batman figure in stylized environments.

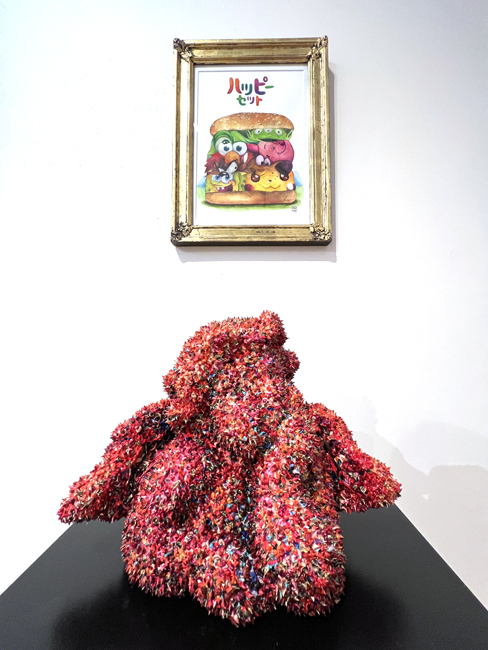

Urban Pop features multiple works by Lindsay Clark, among them the large-scale sculptural piece Kitschbild: Vase (2020), which depicts large porcelain-looking vessels seemingly dripping with overflowing paint. Among the toilet-like vessels are hands, a young girl, and a chicken, adding to the kitsch referenced in the title. The work is an unsettling and fascinating visual rumination that likely resonates within Utah’s highly conservative culture, replete with homes that bear grandmotherly tokens such as these. Elsewhere, Lindsay Clark uses texture and color in intriguing ways, such as in Kitschbild: Sea Sun (2021) and the Andres Serrano-like Sunset Drive, Rose, Park.

While there’s much local talent here, the show fails to discern the stylistic and art historical differences between Pop Art and street art, and at various points, conflates the two. What results is a superficial “greatest hits” collection of selected artworks chosen for their visual similarities to popularly recognizable artists within the Pop and street art canons, respectively. For example, Brian Dean Christensen’s ceramic piece Repurposed Rug harkens to the recently passed Claes Oldenburg while Ruben Rojas’s work recalls Robert Indiana. Patrick Nagel’s Mirage is a contemporary counterpart to Roy Lichtenstein, and Kym Bloom’s work is reminiscent of French street artist Invader.

Laurence de Valmy’s Niki’s Inflatable Nanas (2022) portrays Niki de Saint Phalle’s famous Nanas sculptures as an Instagram post. This concept is impossible to distinguish from Richard Prince’s infamous and shallow digital appropriation New Portraits Gagosian fiasco, for which the artist was involved in years of copyright infringement litigation.

Regarding the internationally famous names in the exhibition, their selected works are, well, lackluster. Proto-pop pioneer Jasper Johns contributes a lithograph poster for a 1968 Merce Cunningham performance, while Peter Max’s etching is a simple portrait sketch. Contemporary art phenom Kehinde Wiley—known for his 2018 presidential portrait of Barack Obama—provides a colorfully decorated basketball bearing the artist’s signature. Saint Phalle’s sketch lithograph Dragon Mother (1996) is perhaps most visually compelling among the big named artists. In all, the aforementioned selection begs one to wonder if mere access to the work of famous artists does anything to affirm their art historical importance or illuminates their role in shaping their respective movements.

Pop Art—at least in its early stages—was often misunderstood as an endorsement of the capitalist imagery its artists were instead using in a formal and theoretical way. It’s perhaps easy to see how the superficiality of Pop Art subjects can be conflated to capture any artistic undertaking that is colorful, whimsical, or in some way references popular culture. But without any interpretive labels, save for a sparse introductory statement, Urban Pop curator Marshall misses an opportunity to make the case for how the works are illustrative of these movements and sub-movements, which despite their similarities, share some important differences.

Urban Pop continues through September 10, 2022, at Bountiful Davis Art Center, 90 North Main Street in Bountiful, Utah.