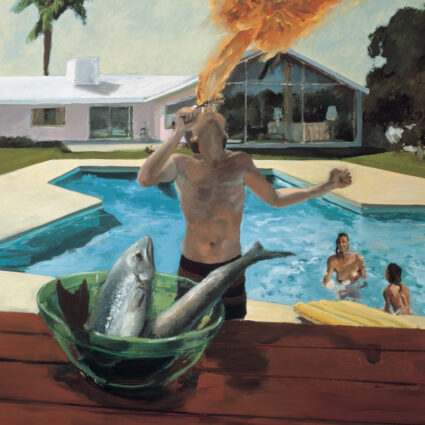

The large-scale paintings of recent Salt Lake City transplant Amber Tutwiler blend figural realism with abstraction to uncover the myriad ways in which technology dislodges notions of the self.

Amber Tutwiler has a longstanding interest in doubles, doppelgangers, and twins. She relayed this unique fascination to me on a hot day in early June 2022 from her studio in the Urban Arts Alliance building in west Salt Lake City. Located on an upper floor of a large arts complex, the studio’s large windows allow for natural light and views of the nearby freeway overpass, a stone’s throw away from the city’s once bustling Gateway mall and a number of music venues. Conversing over vegan croissants and coffee, we covered a range of topics from the art scene in her native Florida to Freudian psychology and beyond.

Tutwiler’s work blends two aesthetic languages often at odds with one another—figural realism and formal abstraction. Central to her series of large-scale paintings is a psychologically compelling investigation of how one’s body—and by extension oneself—are altered through the lens of technology and how the media we all use to connect us has in turn driven us further apart.

To Tutwiler, an artist and studio art professor who recently moved to Utah to join the faculty at Utah Valley University in Orem, twins and doubles are compelling because of the innate human desire to see oneself externalized in objective form. Many of us can recall the distinct moment at which we realize, with difficulty, that we will in fact never be able to see ourselves the way others see us. This realization has not deterred Tutwiler. Her paintings mine the implications of phenomenology—namely the ways in which technological media simultaneously augment and distort our self-image.

Her work that’s featured in a group exhibition i know you are, but what am i? (De)Framing Identity and the Body (June 24, 2022 through January 7, 2023) at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art in Salt Lake City fits the bill. Her paintings contain elements of hyper-realism subsequently fragmented and distorted within the composition, oscillating rhythmically throughout the canvas. She begins by photographing herself in domestic spaces, namely in her own bed, before dislocating and reimagining them as distinct sections within the composition.

“I start with pure symmetry and then completely break it apart,” she says.

There’s something ritualistic, even obsessive about her process of photographing and staging, only to dismantle the once unified image—a process of continual motion. This reminds of Freud’s notion of the repetition compulsion, which denotes the human propensity to repeat in order to break trauma or overwhelming sensations into smaller, more manageable parts.

The idea of bodily transformation within popular media, particularly female-identifying bodies, is of course a rich topic within art historical discourse—think Laura Mulvey’s notion of the male gaze from her seminal 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Of particular interest to Tutwiler is the psychological implications of willingly offering oneself up to be technologically modified, through social media for example. Hers is a reoccurring art historical motif—the German Expressionists come to mind as a cohort particularly aggrieved by the technological implications of warfare—yet granted prescience in a world replete with social media conglomerates wreaking havoc on an individual and macro level.

“I’m interested in the way an identity becomes fractured through that lens, how we willingly disembody ourselves through social media. How sometimes duplicates exist but aren’t quite identical,” she tells me.

In this schema, the viewer is left to conduct a gestalt-like process of putting together the disparate fragments. Tutwiler depicts human forms blurred as if in active motion, what she calls “artifacts of digitality.” These fragmentary glances of human forms are haunting, and oddly erotic as one detects the vestiges of the intimate domestic spaces where the body exists, often uninhibited by the human gaze.

She relishes the human dramas viewers may construct for themselves while viewing the paintings, and the narratives one may construct around the visual hints peppered throughout the multi-faceted compositions. To be sure, her works are unrelenting, evoking a sense of visual and emotive labor ignited by the tantalizing fusion of figural realism and abstraction.

Perhaps it’s unsurprising that Tutwiler, a former dancer, and gymnast, would be primed to consider the nuances of how one’s body informs identity. As an artist, she enjoyed a dynamic and cooperative atmosphere in her native South Florida, describing the artist-led efforts and pop-up exhibitions that she longs for in Utah. And while she is still getting to know the Utah art scene, she was immediately taken with the state’s breathtaking topography.

The shift out West initiated a novel approach to her method of painterly abstraction. While she’s always experimented with abstraction, she found a surprising conceptual connection during her move to Utah and in particular, the sweeping mountains encircling the Salt Lake Valley.

“I see a similarity between my abstraction and the compressional force of the mountains over time,” she notes of the geological forces shaping Utah’s famous peaks. “The diversity of the mountains inspired me, [as] my work is a landscape and an escape of some kind,” she says.

Perhaps the seemingly unending expanse of Utah’s landscape mirrors the infinite digital landscape that, despite its promise of boundless knowledge, often imposes psychological destruction by promoting a single archetype of female beauty. Art at its most profound visualizes connections ranging from the large and unfathomable to the intimate and personal. By traversing landscapes both literal and conceptual, Tutwiler cajoles the complacent viewer into the role of active participant.