Texas artist McKay Otto, deeply inspired by the work of abstractionist icon Agnes Martin, creates ethereal, geometric paintings on translucent canvases that evoke lightboxes.

WIMBERLEY, TX—The snaking dirt road that leads to Everland, artist McKay Otto’s home and studio in the Texas Hill Country, is dotted with curious outdoor sculptures—granite abstractions by Jesús Moroles, a pyramidal stack by Margo Sawyer, and a peculiar piece Otto made by threading organ pipes onto the skeletal limbs of a dead tree. These surreal offerings only reveal themselves to patient eyes. Drive too quickly and they vanish into the rustic landscape around them. Fittingly, this slightly bumpy approach reflects Otto’s long and winding journey to becoming an artist—and making work that begs viewers to slow down in order to truly experience it.

Growing up in Fort Bend County, Texas, Otto often drew on the flour sacks and countertops at his father’s grocery store. His first models—two endearing women who frequented the store—were rewarded for their services with treats Otto swiped from the candy counter. Dad was not amused.

“All I ever wanted was to be an artist and he persuaded me not to go to art school,” Otto says. “He said I would never make a living as an artist… I shouldn’t have listened to him.”

Instead, Otto studied real estate and graduated from the University of Texas at Austin in 1970. Although he thrived in real estate for more than a decade, he became disillusioned and threw in the towel in 1985.

That same year, Otto embarked on a journey of self-discovery. He enrolled in art classes at Austin’s Laguna Gloria. And an unexpected invitation led him—along with his then-wife—to a Los Angeles theater to meet Shirley MacLaine. That convivial visit prompted Otto to read MacLaine’s book Dancing in the Light and he became fascinated by her accounts of past-life regression work at Chris Griscom’s Light Institute in Galisteo, New Mexico.

“I had never been to New Mexico in my life,” he says. “But I got in the car without a map and drove to Galisteo.” As Otto tells it, his first sessions at the Light Institute—which entailed acupuncture with gold needles and “inner visual association with light”—allowed him to access the life of Michelangelo and even the painting of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. “The incredible colors, the smell, the scaffolding, everything… it was the most profound experience I’ve ever had in my life.”

In 1986, Griscom invited Otto to Sedona, Arizona—a location she chose for its powerful ley lines. “That week, I spent my time in the body of Claude Monet,” he says.

Otto is aware of how these experiences might sound to a skeptic.

“It’s interesting what your ego will tell you: that you didn’t experience this, you couldn’t have,” he says. “But yet it was so real… what you’re doing is opening the door to universal consciousness. If you’re smart, you’ll bring that energy back and use it in this lifetime. That’s what I did.”

That same year, Otto divorced his wife. “I was a gay man married to a woman,” he says. “I couldn’t live a lie anymore.”

By the mid-1990s, Otto had completed a two-year program at Houston’s Glassell School of Art and was exhibiting regularly—from found-object sculpture to mixed-media works atop jigsaw puzzles.

Otto’s life took another important turn while he was summering in Santa Fe, where he still lives part-time. Hoping to repay Otto for a few good deeds, gallerist Arlene LewAllen offered him a few favors.

“She said, ‘I’ll try to be the genie: you rub the bottle,’” Otto recounts. “I had just come back from the Whitney Biennial [with] an Agnes Martin book and couldn’t put it down. I said, ‘Arlene, I would give anything to just meet Agnes Martin—she’s got to be my favorite artist of all time.’ She laughed and said, ‘McKay, she’s a recluse living up in Taos.’”

Although it didn’t go exactly as planned, Otto did meet Martin in the summer of 1997—and broke the ice by telling her she “wasn’t a minimalist.” Over the course of two summers in Taos, Martin mentored Otto. While he drew inspiration from her ethereal work—often grids on large-format canvases—she was impressed by his ability to shift between painting and sculpture. “She would say, ‘I’m stuck on a two-dimensional plane.’ It was a dilemma for her,” Otto explains.

When they weren’t discussing their creative trajectories, the pair pondered Mark Rothko’s work, the perfect cobalt blue of the sky, and art’s ability to transport viewers to other worlds.

Those experiences with Martin—who passed away in 2004 at the age of ninety-two—made deep impressions on Otto and his work. “I don’t see the world like I did before,” he admits.

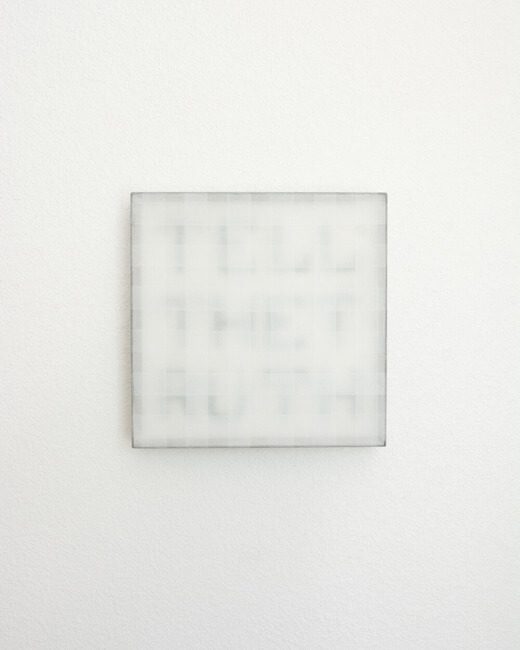

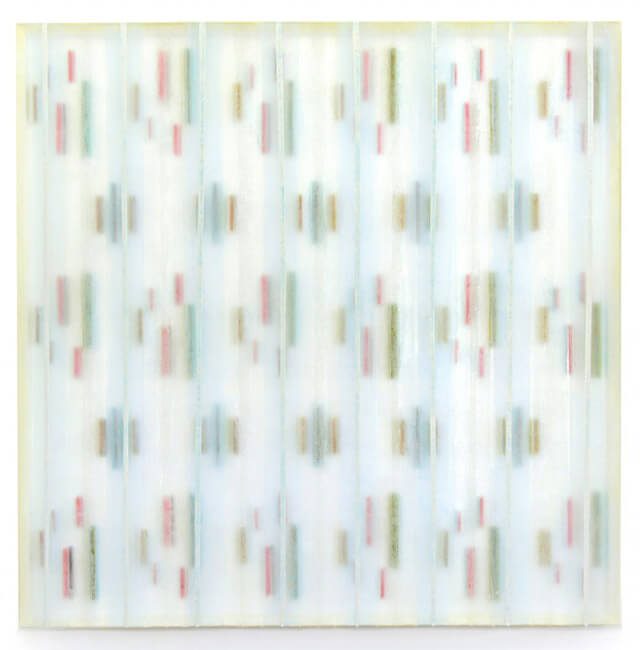

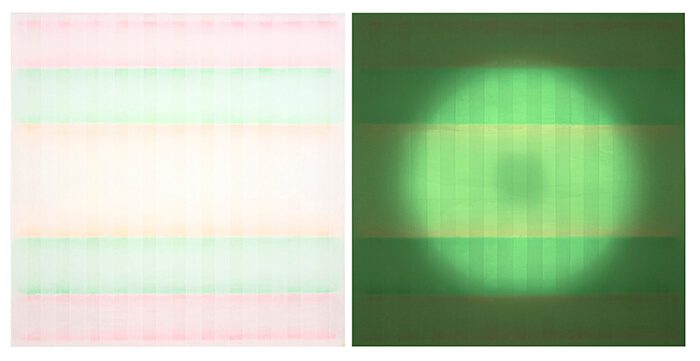

Importantly, Martin’s conundrum of being “stuck on a two-dimensional plane” has become a guiding light for Otto, whose signature style takes her spare abstractions into mysterious three-dimensional realms. With simple geometric forms—lines, grids, circles—among his visual vocabulary, Otto layers paint on “transparent canvases” he stretches with a synthetic material with an amusing backstory.

“It’s a very special material that was designed for the Ice Capades—specifically for Peggy Fleming’s stockings,” Otto explains. “The skaters kept getting runs and this material is the strongest of its kind.” When it went out of production in the early 2000s, Otto purchased all that remained of it. “I have the world’s supply of one of the most critical things in my process,” he says.

A true testament to their ethereal quality, Otto’s paintings defy quick glances. Devoid of hard lines, they can appear to be drifting out of focus or fading to white before your eyes. During a rare critique with Louise Bourgeois at one of her New York City salons, she leaned into one of Otto’s paintings and exclaimed, “There’s nothing there!”

Beyond the three-dimensionality created by the translucent fabric, his paintings also seem to emit light—which is far from an accident. Otto’s prime mission has been to create “lightboxes” without cords or electricity. Perhaps the most instantly gratifying examples involve glow-in-dark paint—a medium Otto says Martin suggested to him in a dream.

“The work is quiet,” Otto says. “You have to spend time with it. It has to be experienced… Agnes told me one day, she said, ‘McKay, your whole process has been about making the material world go away.’”

Naturally, Martin’s similarly quiet work factors into the impressive art collection on display in the airy home Otto shares with longtime partner Keith Coffee. In the high-ceilinged studio where Otto creates and meditates, new projects are piling up—including a text-based series and stacks of small lights boxes wrapped in his “magic material” and aglow with muted fluorescents that echo the fiery colors of Santa Fe sunsets.

With four exhibitions on the horizon—one will be at the forthcoming Canyon Road gallery Atelier Santa Fe—2022 is shaping up to be a busy year for Otto. “It’ll be a big year,” he admits. “But I’ve worked very hard… my process is leading me closer and closer to the true essence of now. And now is everything.”