Artist Adriene Jenik puts a human face on the tragedy in Afghanistan with her Data Humanization Project, which examines the impacts of America’s militarized culture.

PHOENIX, AZ—A fateful decision made twenty years ago continues to reverberate as America undertakes its withdrawal from Afghanistan amid violence, chaos, and uncertainty.

Like many Americans, Adriene Jenik recalls United States President George W. Bush launching a global war on terror following the September 11, 2001, attack that killed nearly 3,000 people. At the time, Bush claimed that military action was needed to eradicate terrorist groups in Afghanistan and prevent Saddam Hussein in Iraq from employing nuclear weapons.

The move prompted Jenik, an artist and educator based in the desert Southwest, to begin an ongoing series of performative actions. Titled the Data Humanization Project, it speaks to the militarization of American culture within the broader context of the colonization of Indigenous lands.

The work is deeply personal for Jenik, a professor of intermedia in the School of Art at Arizona State University in Tempe. Jenik, who uses she/they pronouns, recalls being in New York City during 9/11 and says she’s always been mindful of the ways America’s military actions impact her own existence.

“I struggle as a person and an artist with the extent that I’m complicit with those actions,” they say. “There’s a palpable sense that the way I live is deeply connected with this military might.”

The data visualization series began in 2010 with a durational performance about America’s involvement in Iraq. Jenik spent three days in a small hotel room in Phoenix, making a mark on the wall for every Iraqi civilian death since the U.S. invasion in March 2003. She titled the work 3 Days of Counting (7 years of war).

After reading a declassified U.S. Senate report on torture, Jenik created another durational performance, titled 56 Hours – NOT IN MY NAME (2015). Citing CIA documents indicating this was the shortest amount of time detainees were forcibly prevented from sleeping, she stayed awake for fifty-six hours doing activities that called attention to the practice of torture while celebrating those who refused to undertake it.

“I begin every piece around a number, a piece of data that troubles or confounds me,” Jenik says. “With data visualization, I’m taking massive data sets and feeding them through my body so they’re more comprehensible.”

Sometimes that data is easy to get; other times that’s not the case.

“We think that we have all of the data,” Jenik says of many Americans’ assumptions that they’re getting reliable information about the government’s activities. “But that’s really an illusion.”

By way of example, she cites the Taliban’s swift takeover of Afghanistan amid the American withdrawal earlier this month.

“In 2018, I discovered a significant curbing of the release of information about key Taliban metrics,” she recalls. “Before that, the information was declassified so you could get access to it.”

Classifying the information meant Americans weren’t paying attention to the Taliban’s rise, she says, even though journalists in Afghanistan were seeing the emergence of a shadow Taliban government.

As part of her art practice, Jenik captures data from multiple sources such as government documents and reporting by investigative journalists. “I do a lot of research before I do these pieces, so I’m in the right frame of mind as I’m doing them.”

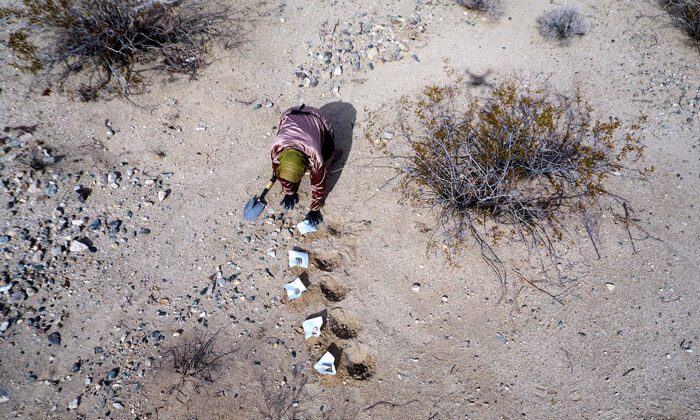

With The Sky is Falling… (2016), they worked with the number 616, a contested figure for the number of civilians killed by U.S. drone strikes during particular periods of time in Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, and Afghanistan.

From sunup until sundown on November 12 that year, on a flat expanse in Twentynine Palms, California, Jenik memorialized each death by digging a small hole, then laying a white cloth and small stone atop each earthen mound, creating a pattern within the desert landscape.

A drone flying overhead documented the performance, which was live-streamed and projected onto a large screen in a gallery space at ASU Art Museum in Tempe during the Ana Mendieta: Energy Charge exhibition.

Jenik has streamed other performances in the series as well. “It’s a proxy for things that can’t be seen, and I cast viewers as my eyewitnesses.”

In 2018, Jenik created Blast Radius to mark the one-year anniversary of America dropping the “mother of all bombs” (also known as MOAB) in eastern Afghanistan. Here, Jenik walked the interior of a one-mile circle of land in Arizona, a distance equivalent to the direct impact of this particular explosive.

“I consider myself an activist as well as an artist,” they explain. “Art can create this space of empathy and recenter the knowledge that people are being affected.”

Despite the U.S. decision to leave Afghanistan, Jenik expects that America’s identity and economy will continue to be rooted in militarization.

“I don’t believe this is the end of the wars,” she says. “It definitely won’t be the end of this body of work.”