May 31 – June 30, 2019

Charlotte Jackson Fine Art, Santa Fe

Thirty miles north of Ciudad Juárez, at an immigrant detention center in Chaparral, New Mexico, Johana Medina Leon, transgendered and from El Salvador, complains of chest pains. Days later, and a day after James Drake’s opening, Que Linda La Brisa, Leon dies on a hospital bed at Del Sol Medical Center in El Paso, Texas.

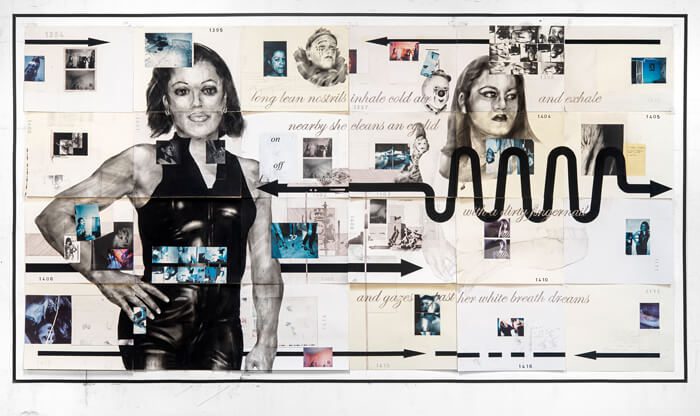

Twenty years earlier, a local artist, Drake found himself in the borderlands of Ciudad Juárez and El Paso with a sixteen-millimeter camera in a sordid flop house shared by a community of transgender sex workers. Unidentified speaker: “Yes, because why do we use coke? Why? Because we get depressed. And we don’t understand that it could have been a problem that we could have resolved just by breathing instead of, you know, doing some lines.” In Que Linda La Brisa, 1999, a group of eight to ten sex workers share stories of police abuse and the violence of life as prostitutes in a noticeably relaxed tone as they pass around a two-liter bottle of Coke and smoke cigarettes, while putting on makeup before heading out to work for the night. It’s strange to witness them so comfortably vulnerable, sharing personal stories and dreams in the presence of a camera. Somewhere between ethnography and journalism, Drake captures the lives of these prostitutes of Zona Mariscal in a split-screen format that is dizzying at times due to the constant cuts of haunting details of clown masks, makeup, and high heels; close-ups with the lo-fi production value of an unstable hand-held camera; and the occasional onscreen cameo of Drake and crew. It’s no wonder Drake was included in the 2000 Whitney Biennial with this project. Only later did I learn that Drake met this group of transsexuals after years working with the Mexican Federation of Private Health and Community Development Associations in Juárez. Start here. This is the pulse of the show and an introduction to Brenda and the others portrayed in Drake’s collages that hold every wall in the gallery with ease.

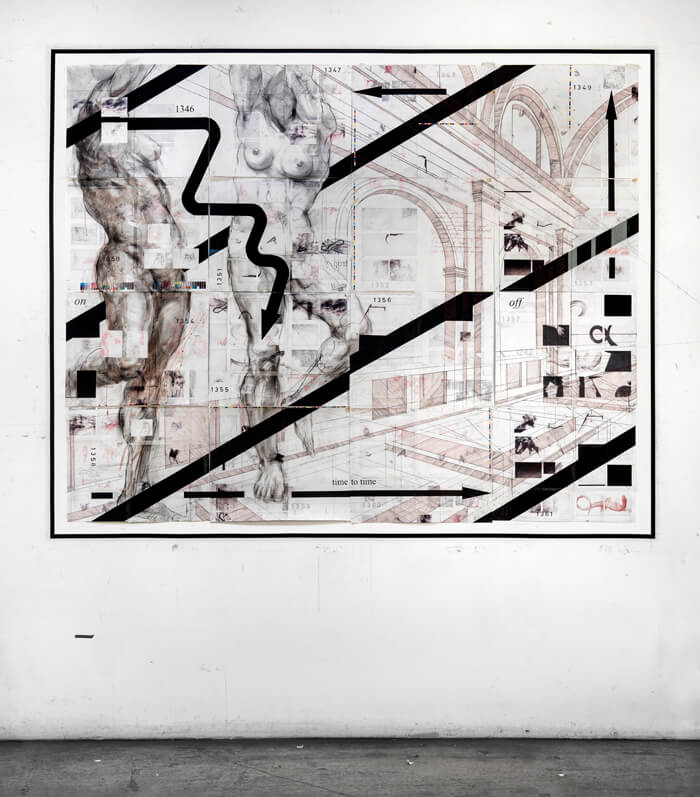

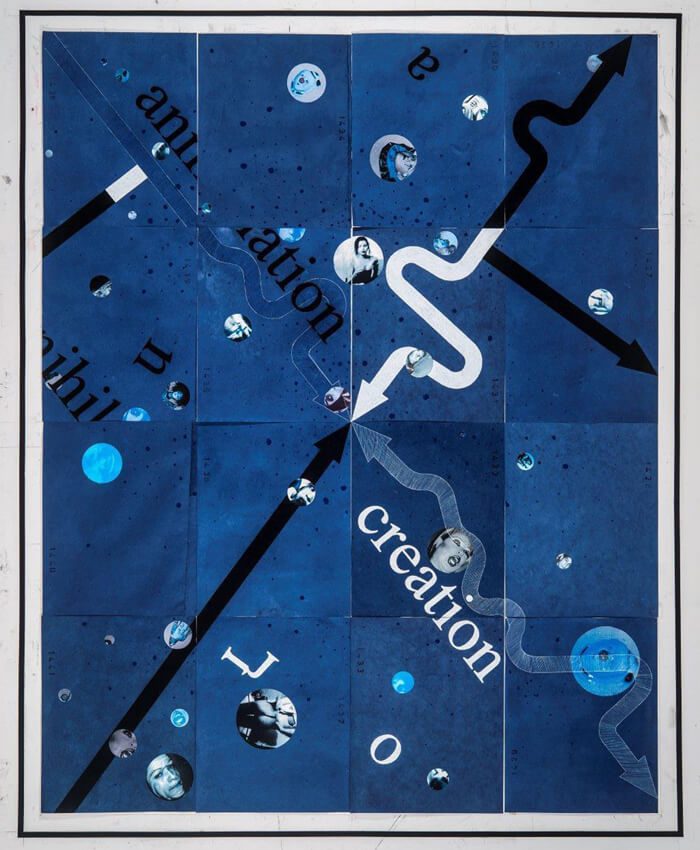

Drake’s monumental collages operate as mimetic machines of desire to slow down, amplify, and map the lives of the sex workers documented in the video. All works consist of charcoal, ink, graphite, and collaged photos on paper, with a foundation of thick, graphic line work to command intersection, direction, and velocity. There’s rapid movement in the frames of these collages. We Pant for Revelation, 2016, an outlier of the grouping, with Dadaist sensibilities, is a large indigo block that slowly fragments into a gridwork of panels with subtle tonal shifts that remind me of cyanotypes developed at different stages. Three arrows converge at the center; the words “creation” and “annihilation” rest in tandem on a diagonal axis and echo Drake’s conversation of dualities and interest in tensions created by borders, real and psychological. The collaged element within the image is formed by constellations of clown masks, scenes of Brenda, and other moments witnessed in the video.

This exhibition of intimate scenes stirs up a deep level of empathy and a chill for a marginalized community of sex workers, only a short five-hour drive from Santa Fe but imprisoned by an entirely different world of drugs, violence, and disease in their search for a better opportunity. Occupying a similar territory with Drake, Argentine artist Ana Gallardo, whose work deals with issues of violence and aging, has documented retired sex workers at Mexico City’s shelter for prostitutes, Casa Xochiquetzal. Tragically, unlike those in the work of Gallardo, the sex workers in Juárez lead short lives, and most everyone seen in Que Linda La Brisa has been dead for some time.