April 26 – May 25, 2019

Evoke Contemporary, Santa Fe

Interlopers is a show of works on paper at Evoke Contemporary that brings together eighteen artists and uses the term “works on paper” broadly, representing a wide range of media, including charcoal, chalk, ink and graphite drawings, etchings and lithographs, watercolor and oil paintings, paper sculpture, photography, and, oddly, one acrylic on canvas. Paper is the only thing that truly unites the work, and the show doesn’t shake a feeling of randomness that the title Interlopers attempts to smooth over. Despite feeling scattershot, the exhibition does find its moments in smart pairings and standout individual pieces.

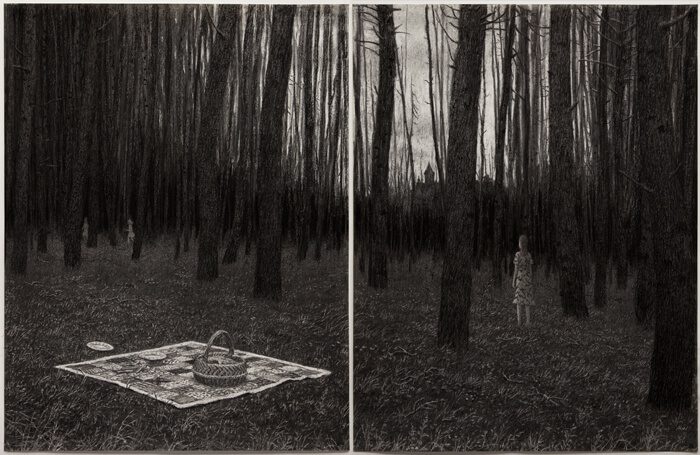

A handful of works find strong companions with each other. The graininess of the black-and-white platinum/palladium photograph and fantastical styling of Beth Moon’s Flight of the Raven is a good match to the storybook feel of Aron Wiesenfeld’s pencil drawings and etching. While the young girl in Moon’s image closes her eyes as if in deep imagination, the lonely, slim-necked women of Wiesenfeld’s drawings exist in foreboding landscapes. They are fragile entities in dark worlds that are inherently dreamy and dangerous in mood—and seem to be beckoning for stories to be built around them, like illustrations or storyboards for uncomposed narratives.

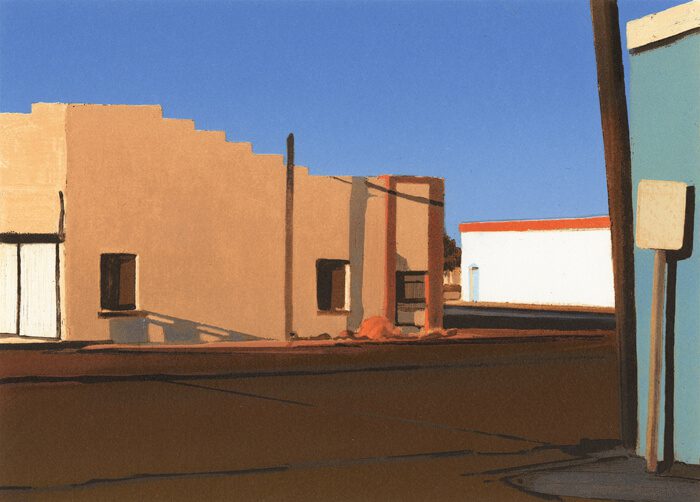

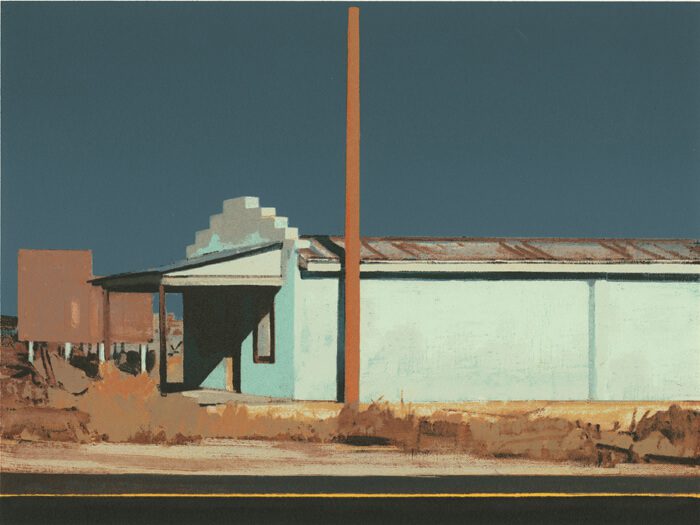

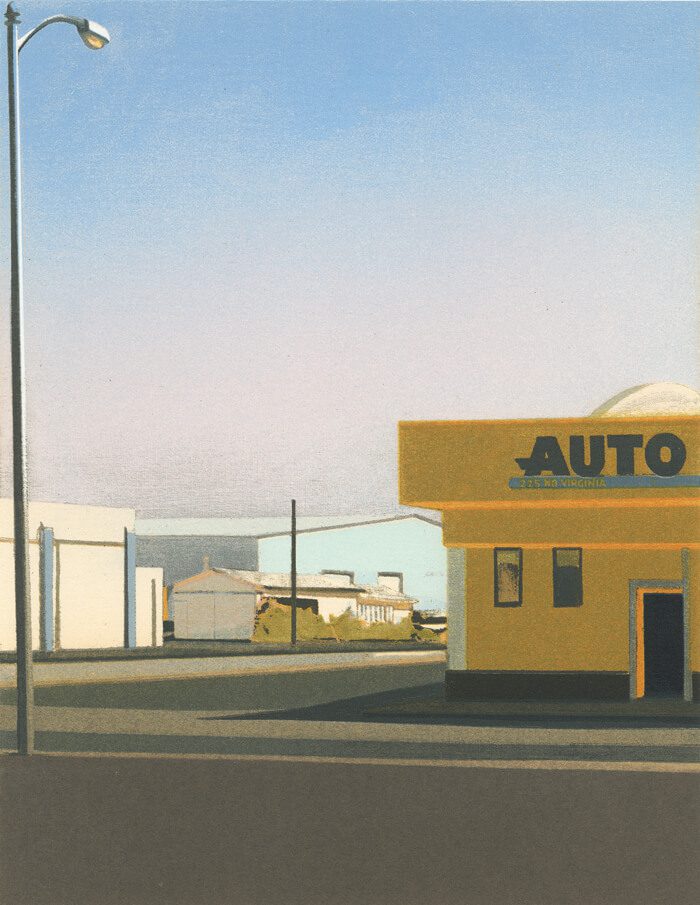

The otherworldly tone established by Moon’s and Wiesenfeld’s works is thrown by the other dominant work in the front room, a series of color lithographs by Christopher Benson and Interbang Press. Occupying the wall directly across from Wiesenfeld, the scenes of New Mexico buildings feel like they could represent what is directly outside the gallery walls. Their color palette of desert browns, reds, and blues combines with the planes of the buildings to find formalness in the mundane.

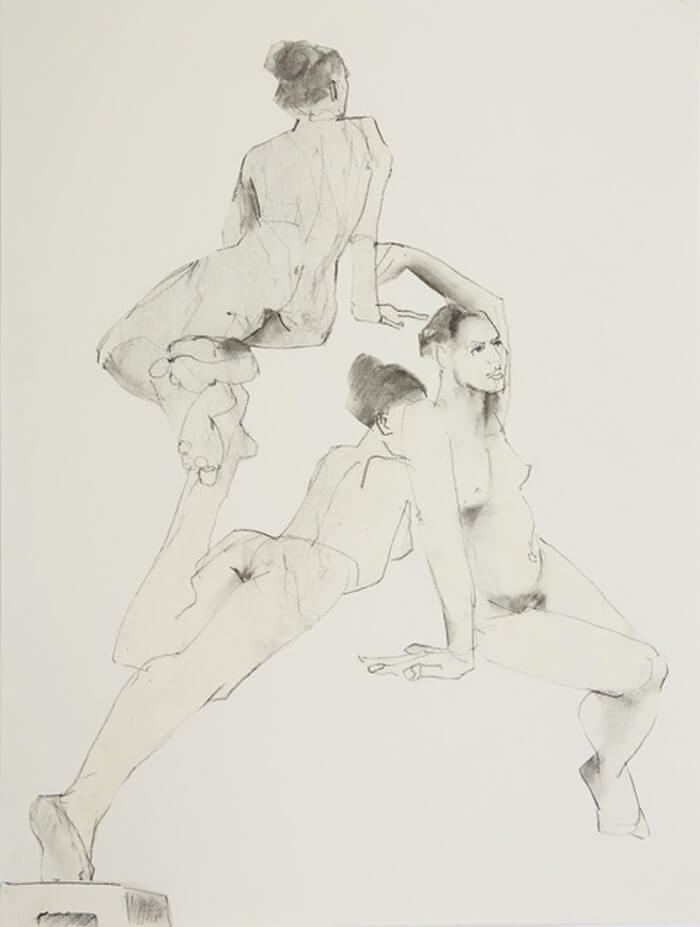

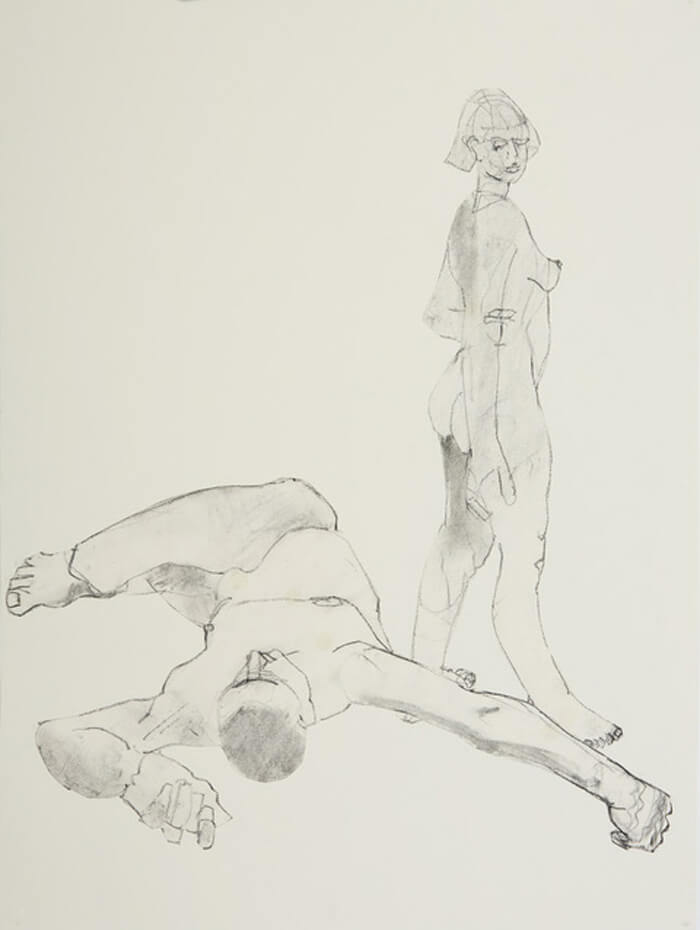

The works of Jon deMartin and Bob Richardson also pair well on a shared wall; the classical style of deMartin’s studies of a hand and hood-draped head have the beautiful textural finish of chalk on toothy paper and create good contrast to Richardson’s expressive pencil sketches. Richardson’s pieces are collages, gestural and playful figures clipped from the sketchbook and pasted onto a clean white page. With multiple figures and poses overlapping, his arrangements gently abstract the shapes that make up his subjects and play with composition and perspective. Several color works share the space with deMartin’s and Richardson’s drawings, including Shely, a photo-realistic oil painting by Yigal Ozeri of a woman wearing what looks to be Israeli military drab and reclining by the ocean, and two photographs, one by Polixeni Papapertrou and the other by Tom Chambers. The photographs share the ocean backdrop and bear a similarity in their fantasy subjects but make for an awkward grouping when the room is considered together.

As one walks around the gallery, a theme begins to surface. Stephanie Inagaki’s three massive charcoal drawings of a pale-limbed woman surrounded by voluminous black hair with braids standing in as visible bones, plaited like the ornate weavings of Victorian mourning jewelry, speak to the three small pencil drawings by Brett Andrus, whose formal portrait composition balances the surrealistic elements that surround their subjects. Even hidden in a corner of the office, the strange pathos of Johan Barrios’s charcoal and watercolor, depicting a woman folded over the shoulder of a man seated in a chair, stands out. And there is more: the refined drawing of a white-haired woman by Soey Milk, Kikyz1313’s nightmarish pile of disintegrating children and hyenas—it felt to me like the body, corporeal and allegorical, wanted to become a theme. Unfortunately, a few too many outlying works scuttle any coherence. To be an interloper is to be somewhere you shouldn’t be, and while none of this work feels unfit for either the gallery or its paper surface, not all of it works well together. The title may have been a bit too apt.