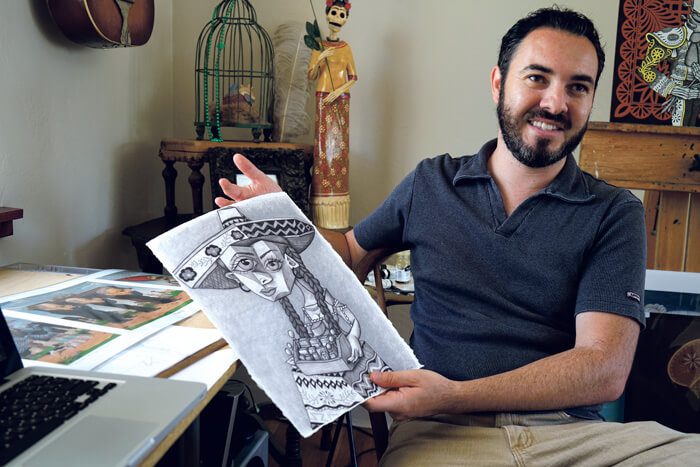

It’s not hard to understand why Brandon Maldonado’s paintings are in high demand. Pop Gallery, which represents him in Santa Fe, sells everything he sends them. From a modest studio in the living room of his rented house in Albuquerque, Maldonado paints images of fictional saints, portraits of family members, and contemporary scenes such as quinceañeras, figures crossing the U.S.-Mexico border, and images of Hurricane Katrina.

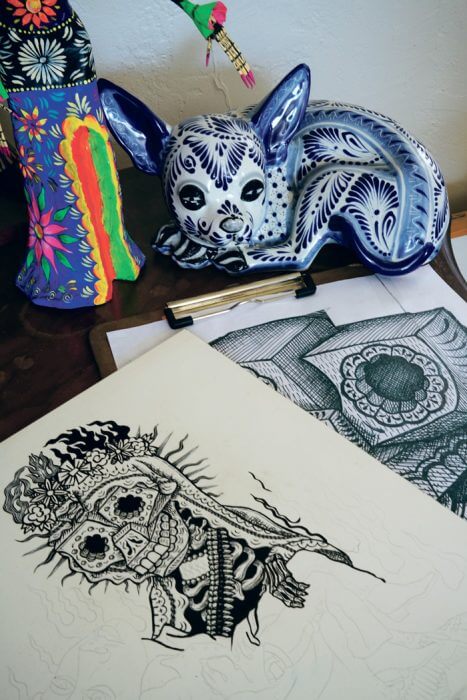

His style borrows freely from Catholic retablos and ex-votos, early Flemish painting, Cubism, and popular culture, all of which Maldonado combines to create colorful and intricate oil-on-panel paintings. Largely self-taught as a painter, Maldonado’s early Día de los Muertos images, which he also sold as prints and on other commercial products to subsidize his painting practice, met with nearly instant success. The popularity of his work has only increased since those early days about thirteen years ago. Maldonado spent his childhood in Colorado before moving with his family to Albuquerque, but for the past several years he has lived a peripatetic life. He moved to Denver, Taos, and New Orleans, each for only a couple years at a time, before arriving back in Albuquerque. His travels in the U.S., Europe, and Mexico have informed his paintings, and as we spoke in his home, it became clear that, while he is comfortable in New Mexico, he is restless for new adventures to inform his artistic practice.

A selection of Maldonado’s recent work is on view at the Spanish Colonial Arts Society through November 25 as part of the exhibition GenNext: Future So Bright. His work Rosa de Camposanto, 2018, is featured on the cover of the September issue of The Magazine.

Chelsea Weathers: It’s nice that we are in your house, because we get to see what you hang in your living space. You have an obvious interest in Northern Renaissance and figurative painting.

Yeah, I have van Eyck and Bouguereau here, but then you look over there and there’s Mexican folk art, too.

CW: Which is sort of how your paintings come together as well, this blending of cultural styles.

A lot of people who know Mexican Baroque painting think that I’m trying to copy that, but it’s just that I’m not good. Those Mexican painters, they didn’t have skills; they would look at European painters like Caravaggio, but they just didn’t have that skill set. So the naiveté that’s in those paintings is in my paintings. I’m trying, just as they were probably trying, but I guess your limitations end up creating your style at the end of the day.

I definitely don’t look at a lot of Baroque paintings, but I think people made that connection on their own. My painting Our Lady of Merciful Fate (2009) is a definite reference to van Eyck. It even has a chandelier [like in The Arnolfini Portrait (1434)]. I made a trip to Europe about ten years ago. I was really looking at the Northern Renaissance. It’s funny: they’re called the Flemish Primitives, but that’s because who was writing the history? The Italians. To me, when I look at van Eyck on a technical level, I don’t think anyone surpasses him. And he was the first one. So I made a point to go to England just to see The Arnolfini Portrait. His work is very fine-tuned and smooth.

CW: When did you start painting?

Painting itself is something that I started when I was twenty-four, and I’m thirty-seven now. But I was always that kid in the class who people would say, “He’s the artist.” I was always making art, but my family never thought that was something that could be a career. So I was discouraged. I was put into wrestling when I was five years old; my dad was trying to get me to do other things. But he couldn’t keep the art away. I just kept at it.

CW: Do you make your living primarily from your artwork?

Yeah, this is all I do. For at least ten years, I’ve been a full-time artist. Before that, I was working at the public schools. I worked as a substitute teacher for about three and a half years, and then at one of the schools I started working at the library, shelving books. I got a summer’s worth of days off throughout the year, so I was able to focus on my art.

CW: How did you get to the point where you were able to quit your day job? It’s kind of a rare thing.

I don’t know. I think I just got lucky. I found a niche. A lot of the work that I was marketing was Day of the Dead imagery. I was trying to sell prints, and people liked it. I started exploring different themes later, but that is still what I’m most known for. A little over ten years ago [my work was used on] billboards around the state, for a campaign that says, “You drink, you drive, you lose.” I still see it all over.

I saw Jimmy Kimmel holding my artwork up, which was cool, but I had nothing to do with it.

CW: And you also did an album cover for the Zac Brown Band.

Yeah, I don’t really listen to country music, but I got this e-mail that said, “We’re on tour. Zac loves your stuff, and he wants you to do the next album cover, and he wants you to come on tour with us.” I didn’t realize that at the time Zac Brown was, like, the biggest thing in country music. The album cover I did [Our Lady of Merciful Fate] was his third album after his big break, and it ended up winning a Grammy for Best Country Album.

CW: So your work was everywhere.

It’s a very strange thing. It’s pretty cool to be a part of that, but then sometimes it’s like when you run into your ex-girlfriend out of nowhere. Like I saw Jimmy Kimmel holding my artwork up, which was cool, but I had nothing to do with it. When it’s something that big, you have to give away all your rights.

CW: How has your work changed from when you first started?

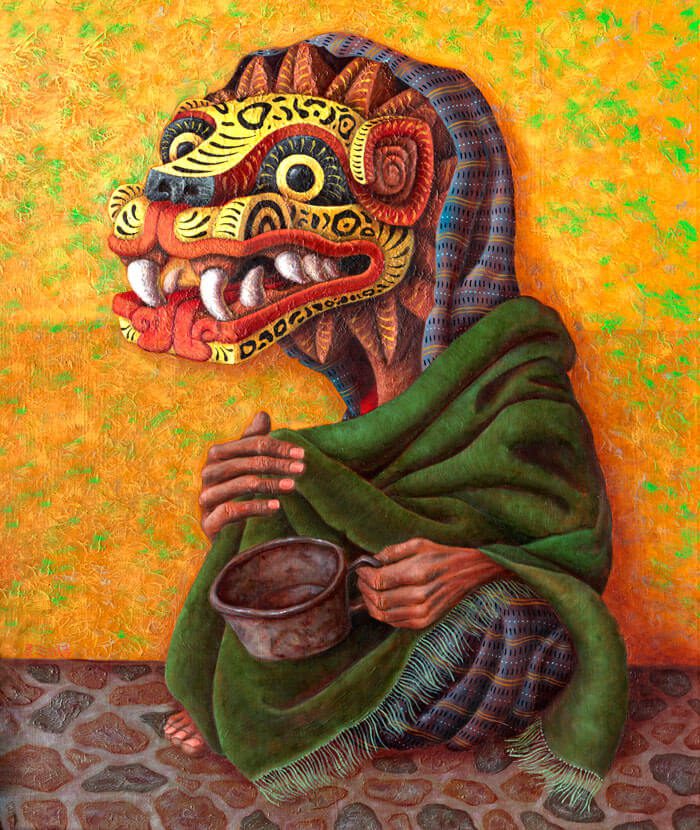

I have an ongoing fascination with Mexican culture. It started with the Muertos stuff and evolved into trying not to be pigeonholed as the guy who does the skeletons. A lot of my work for years was just about curvilinear rhythms, all these organic rhythms, and back in 2012 or so I became fascinated with geometric forms and more modern forms. I think it might have had something to do with moving to Denver. What you see there is very modern, the shape of the museum even. So maybe that’s when I came up with the theme for my current show at Pop Gallery. My show is called Neo-Picassoism. I wanted to explore more geometric forms rather than curvilinear. Also, my application of paint has always been very fine and detail oriented, but with [a more recent painting, The Oppressed (2017)], a beggar on the street with a Quetzalcoatl head, I’ve really built up the paint with impasto. So I’m exploring loosening the paint. It’s something I talked about for ten years before I actually had the guts to do it.

Clayton Porter: You mentioned that your family was opposed to your being an artist. At what point did they see that what you’re doing could work?

I don’t know. My dad just a couple months ago was telling me that I should go back to school and take some classes. So I think he still doesn’t get it. I think he thinks that’s what you do; you don’t sit around and play all day.

CP: Do you ever try to explain to him that it’s working?

I think he has come to understand that. But there were so many years of him saying, “You can’t do that.”

CP: Was there anyone in your extended family who was supportive?

It’s very strange, because both my father’s parents are artists. And he saw his uncle move to California to try to be an artist, and I guess [my father] didn’t think that [my uncle] lived up to what he was trying to do. And when the whole thing happened with the Zac Brown Band, my whole family was excited, but my dad was like, “Well, you don’t have health insurance.” I get along with my dad now the older I get; we’re very similar in some ways, but that’s always a weird thing. At the same time, I’ve seen people in my family, they were told since they were little, like I was told, “You’re an artist,” but then they don’t do it. And I have other relatives who were told they were going to be a star athlete, but they didn’t do it. How many people were told they were going to be president when they grow up? I don’t know if my path is harder or in some ways easier, because you get to a point where you don’t have to prove anything to anybody except yourself.

CW: Do you think you’ll stay in the Southwest? When you move, does it affect your work?

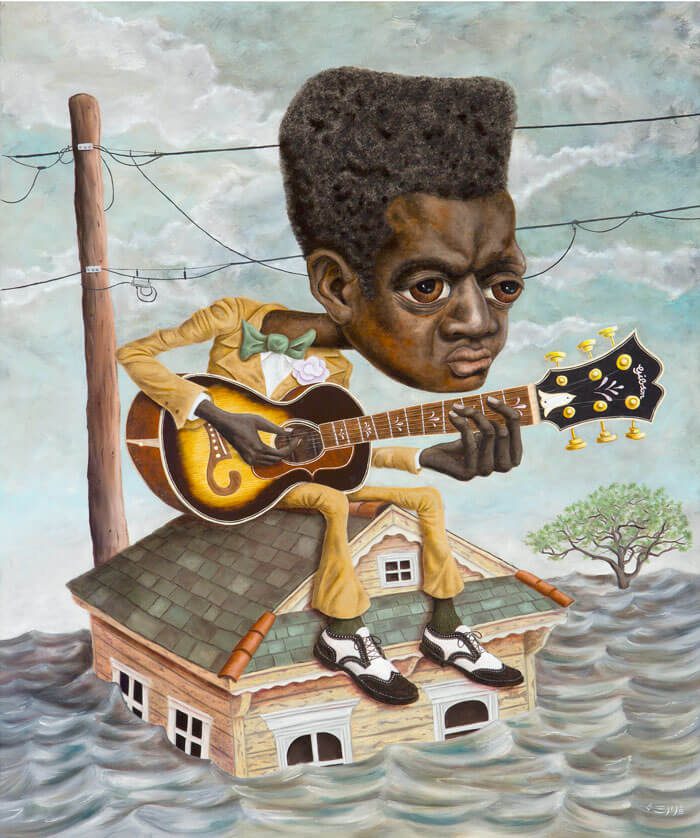

I did a whole series in New Orleans. It was nice to see skeletons in a different context. I had no idea there were skeletons there, but they see it in the context of Voodoo, so it was interesting to think about that subject matter from a different point of view. I did a painting called Water Levee Blues (2015) for a benefit to raise money on the tenth anniversary of Katrina. On some of the houses in New Orleans, you can still see the watermark from Katrina, so it’s a constant reminder, and every day people are talking about hurricanes. It’s kind of weird to live with that fear. So I’m looking forward to going somewhere new. I like what’s going on in San Antonio, and the cost of living is the same as here. I’m not really psyched politically about being in the state of Texas, but when you go there it’s kind of like being in New Orleans, it’s its own little world. The humidity is what has held me back, so I’m still here for now, just lying low. A week from today, I’ll be on a plane going to Mexico.

CW: What do you do when you go to Mexico?

The last time I was there, I was in the jungle, a couple hours north of the Guatemala border, in Palenque and San Cristóbal de las Casas. I always go back to Mexico City. I’ve looked at the pyramids, and [points to a drawing in process on his desk] this style of dress is the china poblana. I don’t even know if she really existed; she’s more like a legend, and she wasn’t really Chinese—she was Asian, so they called her “china.” I learned her story when I went to Puebla. They have this myth that she’s the one that made all these beautiful dresses with sequins and beads. And the background of this drawing is the city of Guanajuato.

We embrace their culture, but we don’t accept them as people.

CW: Some of your paintings seem to have clear references to colonialism, because of the way you are mixing Spanish Catholic and Indigenous subjects.

There’s a lot of tension between cultures, and learning about those stories, I want to retell them. The Oppressed, in particular, is almost the start of that. In Mexico, the reality is that the indigenous, dark-skinned people are still oppressed. You see them out on the street, selling stuff, but you go into the stores and it’s all European-looking Mexicans. We embrace their culture, but we don’t accept them as people. So I’m trying to make some statements, some observations about where we are right now. About ten years ago, the work was more about my personal emotions. I made one early painting, Sleeping with Your Ghost (2011), when my girlfriend moved out of our house. Now life is better, so the work has changed, and I’ve grown past that. But that painting was hanging in a gallery, and a woman who had just been divorced saw it and started crying. It’s therapeutic to me to let those feelings out. If you think you’re all alone, but people react to the painting, then you think, “Maybe it’s not just me.” Maybe it’s a universal thing.