Tewa artists and scholars offer a challenge—along with tea, letters, and a remarkable map—to an institution whose namesake claimed their ancestral lands.

Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country

November 7, 2025–September 7, 2026

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

Last October, just outside Georgia O’Keeffe’s bomb shelter in Abiquiú, New Mexico, Jason Garcia (Kha’p’o Owingeh/Santa Clara Pueblo) plucked a pottery sherd from the dirt. The fragment bore distinct painted stripes, which launched him into a discussion of a wild desert spinach used by Pueblo potters to produce black pigment. “You can also make salad with it,” he noted.

O’Keeffe’s early-1960s cellar stood by, a product of her desire to “be around to see what the landscape would look like if there was ever a catastrophe,” according to a longtime caretaker of the property. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum staffers had just finished telling us that the cinderblock room would have barely fit O’Keeffe and her beloved chow dogs.

As Garcia cradled the sherd and spoke of a long ancestral practice, I imagined gnarled fingers and claws scratching at the lead-lined door behind us.

It’s my private mountain. It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it.

A few weeks later, Garcia’s curatorial project Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country opened at the O’Keeffe Museum, the result of a two-year effort to unite artists from all six Tewa-speaking Pueblos in the downtown Santa Fe space. Co-organized by curator of art and social practice Bess Murphy, the exhibition features thirteen people including O’Keeffe, and splits its energies between interrogating her fraught relationship to ancestral Indigenous lands and exploring Tewa narratives that have little to do with her.

Some of the show’s most compelling moments arrive when those intentions cross and invert, revealing the generosity inherent to Tewa community and land stewardship. The living artists spring O’Keeffe from her bunker, but they don’t treat her as the nuclear art monster I pictured.

Since its founding in 1997, the O’Keeffe Museum has hovered like a modernist chandelier above the regional art scene, oddly minimalistic in its portrayal of a figure who gets harder to encapsulate the longer you study her. O’Keeffe’s high-desert lifestyle may seem to match the museum’s logo font (a spare sans-serif) but a swing through her letters (with their swirling scrawl and rhythmic em dashes) and interviews establishes her impassioned and prickly weirdness.

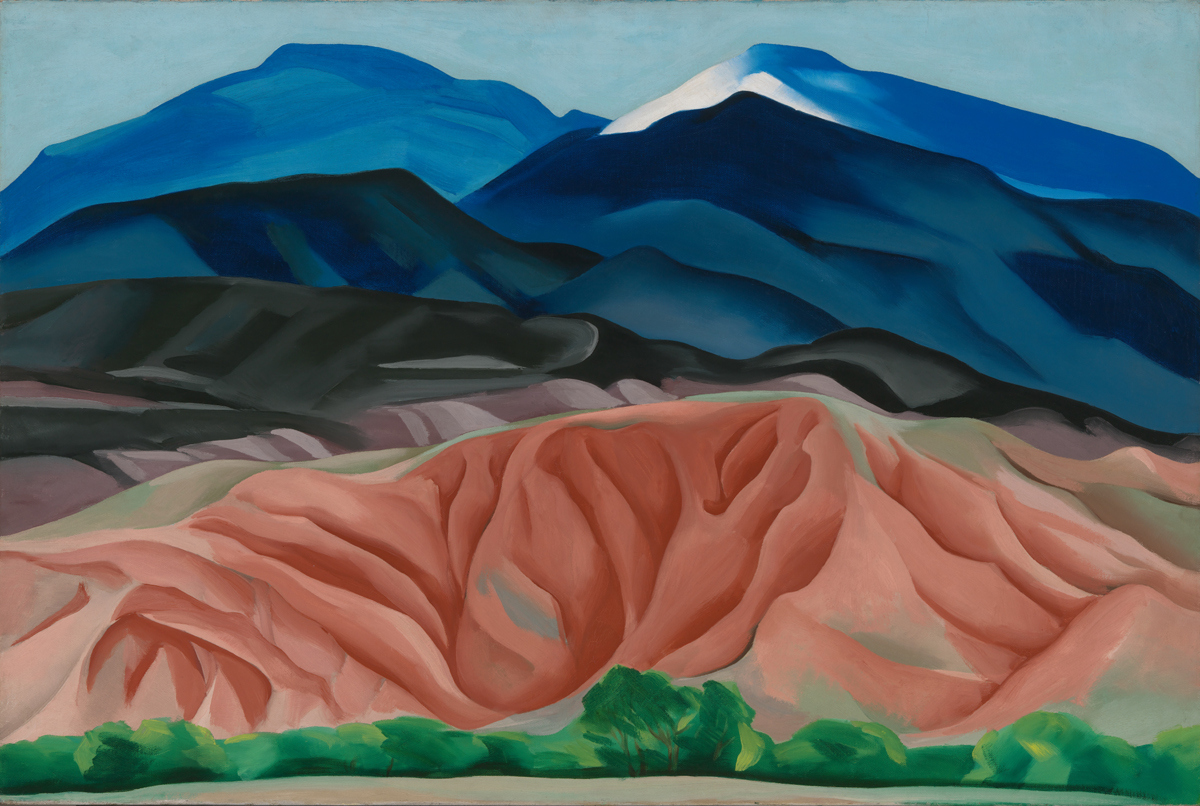

“It’s my private mountain. It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it,” O’Keeffe told a PBS documentarian in 1977. She was talking about the Cerro Pedernal, a mesa that anchors the southern vista from her home in Abiquiú’s Ghost Ranch. This statement, and a similar quote claiming all of New Mexico, mark the show’s entrance and seem to promise a head-on ideological clash.

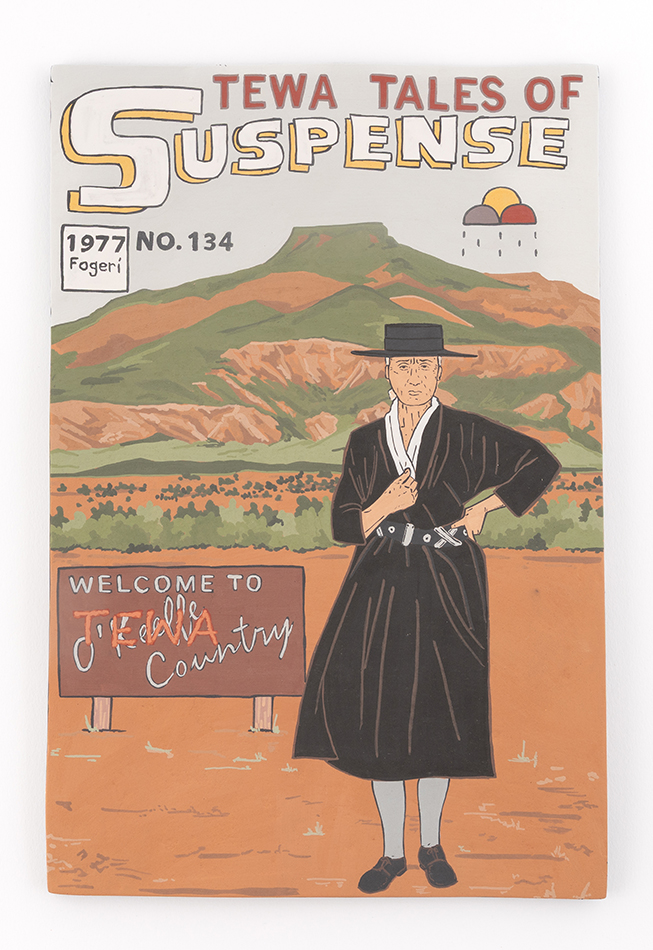

Two nearby images exemplify the show’s dichotomous nature. A clay tablet by Garcia, from his comic book–inspired series TEWA TALES OF SUSPENSE!, shows an elder O’Keeffe with the Pedernal behind her. A road sign next to her announces “O’Keeffe Country,” a marketing moniker used on actual signage, scribbled over to read “Tewa Country.”

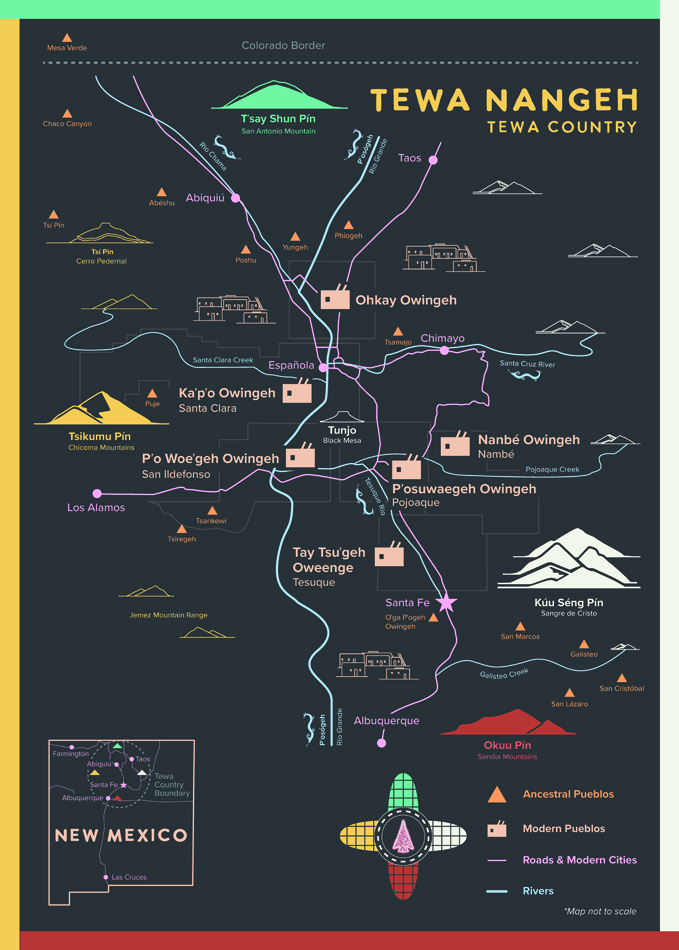

One wall over, an intricate map reveals the Tewa name for the Pedernal, Tsí Pín, and other place names from the “Pueblo world” of Northern New Mexico. It’s a document and a collaborative artwork, shaped by interviews mediating the dazzling variation of Tewa oral traditions. The process of its creation reflects Pueblo ethics of communal care for ancestral lands, which contrast with colonial notions of land ownership. Rather than a militant reclaiming, the map evokes a choral raising of Tewa voices.

Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country proceeds in this zigzag pattern, matching each outright clash with O’Keeffe’s legacy with a softer or entirely separate gesture. Near the show’s threshold is a micaceous clay and mixed-media tea set by Marita Swazo Hinds (Tesuque Pueblo), inspired by the artist’s “surprise” over O’Keeffe’s absurdly large teapot collection.

Hinds tucks Indian (Cota) and Hu-Kwa teas into the tureen, imagining the “simple pleasure” of O’Keeffe’s ritual and wishing for a visit with her. (Elsewhere in the show, she asks, “Did Georgia pray?”)

A landscape mural made with hand-gathered clay pigments by Eliza Naranjo Morse (Kha’p’o Owingeh/Santa Clara Pueblo) fills a central wall and sends the road leading to her home village winding across a platform dotted with sculptures. Among them are works by Martha Romero (Nambé Pueblo) that explore the psychological effects of assimilation in a sculptural trilogy, and the rooting power of ceremonial music via an intricate mixed-media drum and sound piece.

In the back corner of the main room, artworks by O’Keeffe and Garcia alternate with reflections from Tewa doctoral scholars. Matthew Martinez (Ohkay Owingeh) discusses how even “seemingly uninhabited ancestral places” are “alive,” and how O’Keeffe’s landscape art “negates… interconnected and intimate landscape[s].” Joseph Woody Aguilar (San Ildefonso Pueblo) criticizes a painting by O’Keeffe depicting the skull of a Pueblo person inside a shattered clay vessel, explaining that it flies in the face of Tewa “reverence” for the dead.

This exhibition doesn’t ask you to denounce [O’Keeffe] but to watch what happens when her artistic certainty… is made to share terrain with older ways of knowing.

Facing this zone is an art installation of a desk covered in handwritten letters, posted from the present to specific moments in O’Keeffe’s life by Samuel Villarreal Catanach (P’osuwäegeh Ówingeh/Pueblo of Pojoaque). His messages are animated by a bewildered curiosity; at one point he muses, “I’m learning more about you, you seem to travel a lot… [which] suggests a quality of American culture that upsets yet intrigues me.”

Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country feels distinct from the museum’s earlier engagements with Native artists, which—however politically or aesthetically resonant—never tangled with O’Keeffe’s problematics so overtly. This exhibition doesn’t ask you to denounce her but to watch what happens when her artistic certainty about this place is made to share terrain with older ways of knowing and naming.

I kept thinking about a second pottery sherd I saw Garcia pick up in Abiquiú, this one perched on a shelf inside O’Keeffe’s Ghost Ranch house, fully absorbed into the museum’s domestic story. In his hands it wasn’t evidence or a trophy, but a complicated point of contact between him, her, and the land beneath us.