In prehistoric times, the line that connected people to each other was regarded as one of nature’s great mysteries. If you got too close to the line, you couldn’t see it. If you got too far away, you could see it but you couldn’t understand it. If you tried to make sense of the line, you lost your mind. And, if you tried to touch it, the line disappeared.

In prehistoric times, the line that connected people to each other was regarded as one of nature’s great mysteries. If you got too close to the line, you couldn’t see it. If you got too far away, you could see it but you couldn’t understand it. If you tried to make sense of the line, you lost your mind. And, if you tried to touch it, the line disappeared.

After civilization came along and made us what we are today, poets and philosophers began to write about the line. They referred to the line either as “God” or as a god. This was the only way poets and philosophers could use language to suggest the power of the line. Then the scientists appeared. When the scientists tried to measure the line and the line refused to be measured, the scientists pretended to measure it anyway. After years of imaginary measurements, the scientists told us the line was either too large or too small to be seen with the naked eye. If you wanted to see the line, you had to observe it through the enhanced eye of a microscope or a telescope. Either way, you had to know what to look for—otherwise you’d see nothing but air.

At first, our response to the scientists was to laugh at them, but the scientists were nobody’s fools and in the end they had the last laugh. They used what they’d learned about the line to build magnificent weapons, then they gave those weapons to our leaders. “Be careful,” they said. “These are powerful weapons. If you use them to kill your enemies, you’ll end up killing your friends, too, and the line that connects us to each other will be destroyed. But if you learn how to use these weapons by not using them, the human race will survive and the line will be saved.”

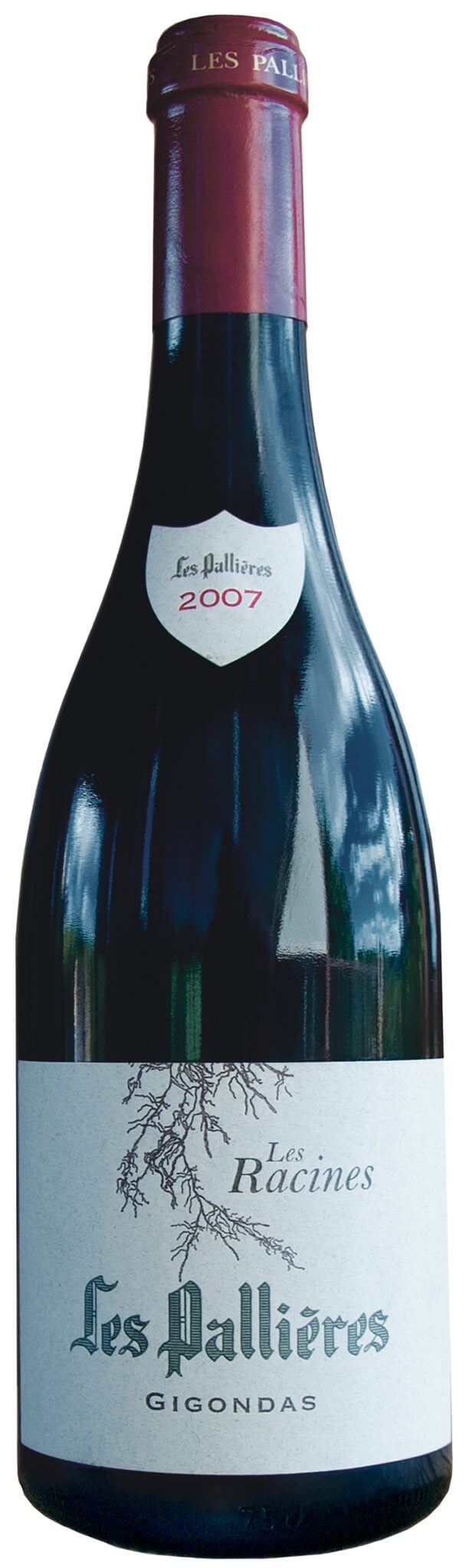

Which brings us to the 2007 Domaine Les Pallières Gigondas “Les Racines.”

Gigondas is a village on the east side of the Rhone Valley, two hours north of Marseille. Domaine Les Pallières is located on 125 acres outside of Gigondas. The terrain is steep and terraced. The soil is covered with limestone talus from the nearby Dentelles de Montmirail mountains. Most of the vines are between sixty and one hundred years old.

In 1998, Kermit Lynch, the Berkeley wine importer, and Daniel and Frédéric Brunier, the brothers who own Domaine Vieux Télégraphe in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, formed a partnership and bought Domaine Les Pallières from the Roux family, who had owned Les Pallières for six hundred years. In 2001, Domaine Les Pallières made good wines. In 2003, 2004, and 2005, Domaine Les Pallières made very good wines. Then, in 2009, the 2007 vintage was released. 2007 was a great vintage in the Rhone Valley, but not every wine made during a great vintage qualifies as a great wine.

The 2007 Domaine Pallières “Les Racines” qualifies as a great wine. In fact, I think it’s safe to say that the 2007 “Les Racines” qualifies as a living wine, a wine you can approach the way you might approach another human being. Clarity and ambiguity rarely appear side-by-side in the same wine. They coexist in the 2007 “Les Racines.” In French, “Les Racines” means “the roots.” When you drink the 2007 “Les Racines,” you nourish your soul the same way a root nourishes its vine.

In the glass, the 2007 “Les Racines” gets lost in the netherworld between crimson and scarlet. Like memories of a happy childhood, the bouquet manages to be simultaneously old and young, controlled and wild, naïve and wise. On the palate, the 2007 “Les Racines” gives a whole new meaning to the word “generosity.” The wine overwhelms you with its depth, then it teases you with the twin promises of love and beauty. When the wine delivers on those promises, you surrender to its generosity. The finish tells you a story. In the story, you’re connected to other people by a line that has no name, and other people are connected to you by a god who plays with large cats and turns sailors into dolphins. The story has no ending. It fades into the sunset, only to reappear as a star in the sky.

In the same way that our future is an unintended consequence of the past, our connection to each other is an unintended consequence of our individuality. We may not understand the line that connects us to each other but we know we can’t live without it. This is why we have dinners. This is why we open bottles, pour wine into glasses, raise our glasses, make toasts, drink wine, and feel the heat and the tension of our affection for each other. After a glass of good wine, we can do what we came here to do. We can speak freely. We can laugh and cry. We can look each other in the eye and not be afraid of what we see.

This is our celebration of the line.