New Mexico Artist to Know Now William T. Carson updates us on his practice since the pandemic, working with sound, and the importance of being patient.

This past March (the one that feels approximately 200 years ago) Southwest Contemporary held its second-annual exhibition 12 New Mexico Artists to Know Now. Selected from over 400 submissions, these are the artists we consider to be shaping the landscape of contemporary art in New Mexico.

Just one week after the opening, however, the gallery closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, these artists have continued to create, in terms of art as well as impact in their communities. We’re checking in with each of them to see how they are, and what they’re making now.

William T. Carson

lives in Santa Fe, NM

born in Birney, MT

williamtcarson.com | @williamtcarson

How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected your process? Has it changed where, how or when you work? Has it changed the subject matter?

I feel that the most powerful way the pandemic has affected my artistic process has been its effect on my mind and my mental state. I am grateful to have stable housing, work, and access to my studio, where I have finished up a few commissioned coal works during the pandemic. Honestly though, finding consistent motivation to get in the studio and continue creating my work has been hard. This is a surreal new world we are living in; some days I’m optimistic that this might lead to radical change in the way we treat each other and treat the planet, and other days I just feel the weight of it all. Isolation, anxiety, and frustration can take a toll on my ability to think clearly and creatively. When I look around on social media it can feel like other artists are cranking away in the studio, but that honestly hasn’t been my reaction or my reality during the pandemic. I know this might not be the most inspiring thing to share, but I want to be honest about my experience and I know other folks out there have been feeling the same way. Responding to our new reality is a process that we are all working through in our own way, and I’m trying to be patient with myself and respect that process. I think it’s alright to take some time right now to think, to listen, to reflect. I imagine a great deal of good might come from everyone in the world being offered a moment of introspection.

What are your top concerns for the arts and your fellow artists?

I’m worried about all of the small galleries and exhibition spaces all over the country that provide opportunities and community for emerging artists. These spaces are the foundational building blocks of the art world—offering a place to share, meet people, and make a living. I’m also concerned about the emotional wellbeing of everyone that finds solace in looking at art with others. During the pandemic, there have been a plethora of digital art experiences, some of which I‘ve loved, but I’ve found that digital experiences cannot replace the reaction and physical understanding I have when I am able to experience a work in person. This hiatus has illuminated the value of gathering to look at and discuss artwork together.

How has your relationship with art-making changed during this time?

Recently I’ve been able to build some creative momentum and start making my way out of the rut I spoke about earlier. Something I’ve found helpful is creating a routine to draw for twenty minutes each morning—trying to let my hands and mind wander without any attachment to the results. I’m a big believer in creative momentum, and simply doing this has opened up new ways of thinking and renewed enthusiasm.

Days and days of quiet time at home has allowed me to dive into digital projects that have been on my mind for years but I simply never made the time for. I’ve found myself more eager to explore new avenues that are less familiar to me, like working with digital manipulation, digital drawing, sound, video, and music. Being outside my artistic comfort zone has been a helpful way to access a flow state and feel free to create without expectation.

Tell us about your current projects or pieces:

Right before everything shut down I started working with sound for the first time. I created sound recordings of the crackling sound that occurs when coal interacts with water—a sound and phenomenon that I’ve been hooked on for the last five years. My friend and sculptor Oswaldo Maciá helped me create sound recordings of coal in my studio. In the past, I created interactive sculptures at a small scale where the audience participated in activating this sound through coal sculptures. During the pandemic, I have been developing these ideas through research, drawings, and models with intentions to find an exhibition space to create an immersive environment that would allow visitors to listen to the sound of coal.

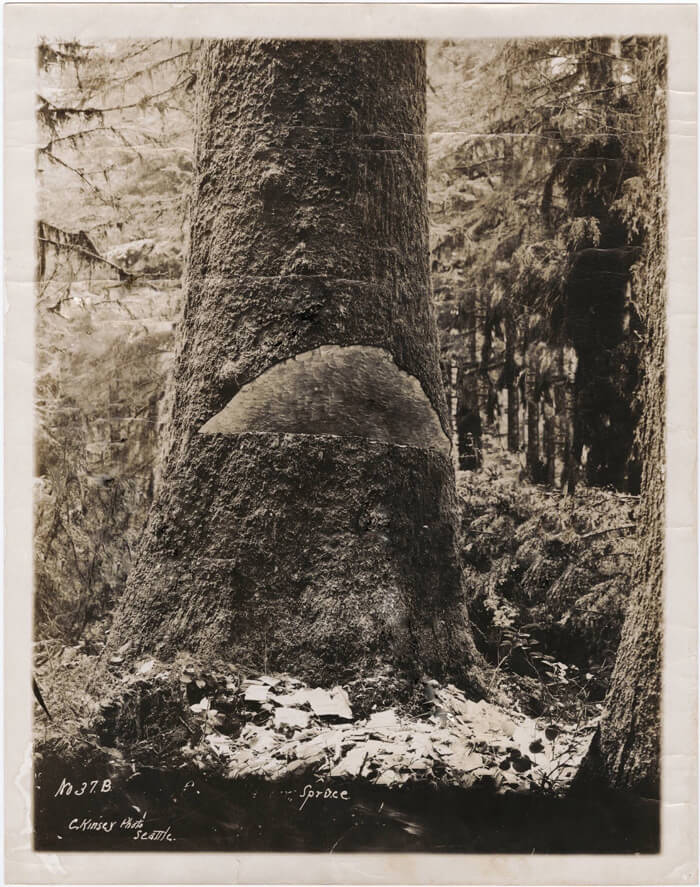

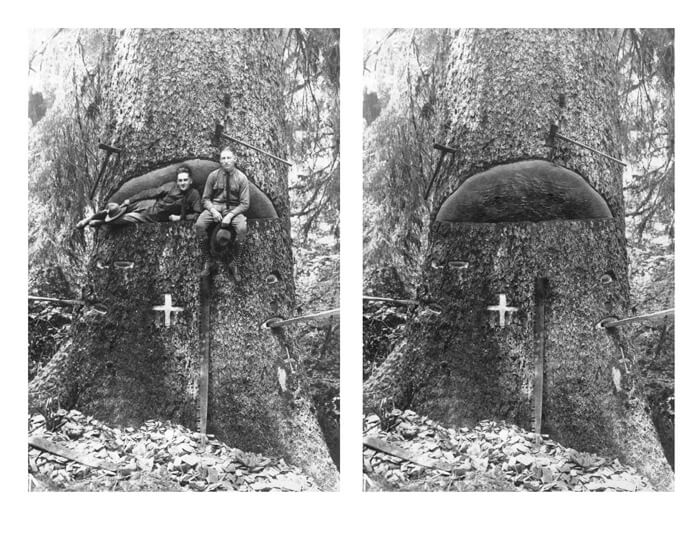

I’ve been working on a series of digital interventions into historic logging photos. A portion of my childhood was spent on an island in the Salish Sea and I’ve gone on two long sea kayaking expeditions in British Columbia in the last few years, so the forest and logging have been on my mind for some time. During a trip to the California coast in 2018, I picked up a book about the history of the logging industry. The images in this book are unbelievable. I became fascinated by one particular style of image from this period (late 19th/early 20th century) that appears to have been quite popular at the time.

Loggers would pose for a photograph during the process of felling a tree, often lying down in the undercut of the tree or standing on springboards next to the undercut. I’m curious about the psychology of these images. In a way it’s a strange form of immortality for these individuals to live on through these images; this form of immortality is only achieved by celebrating taking the life of a tree that has grown strong over centuries—a parasitic path to immortality. Another aspect of these images that I find odd is that they actually remind me of influencer images on social media. Everything is staged and carefully calculated. What was the goal of these images? Who was/is the audience?

In a way it’s a strange form of immortality for these individuals to live on through these images; this form of immortality is only achieved by celebrating taking the life of a tree has grown strong over centuries—a parasitic path to immortality.

In Photoshop I have been manipulating these images to completely remove the people from the scene. What remains is an eerie and beautiful portrait of a wounded tree. The undercut is often a visually striking shape and texture—here you are seeing into the core of the tree while it still stands. I’m interested in exploring what it means to remove these people from the image, playing with history and progress. How does the resulting image change the sense of scale, alter the subject of the image, or ask questions about the mindset captured in these historic photographs? I’m just at the beginning stages of this exploration; the more I work with these images, the more questions arise, so I’m curious to see where this path leads.

Is there anything else you’d like to share?

I would like to send a heartfelt thank you to all the wonderful folks at Southwest Contemporary. The last exhibition I went to before the shutdown was the opening of our 12 New Mexico Artists to Know Now show, which was a real high point in my art career since moving to Santa Fe in 2018. This summer I was selected to participate in the Salina Biennial in Kansas, which I only applied to after learning about it through Southwest Contemporary. Thank you for continuing to share opportunities with artists and for being a hub of connection during this isolated time.