Wren Ross, a Park City, Utah, painter and social worker, plumbs our collective unconscious with stirring, uncanny work, where movement becomes a crucible for visual creation.

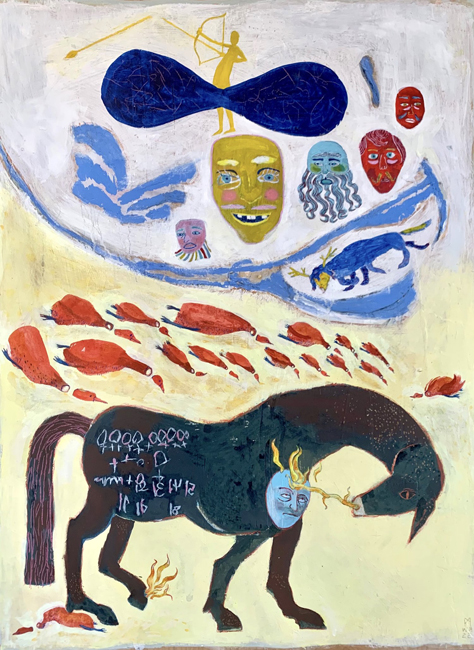

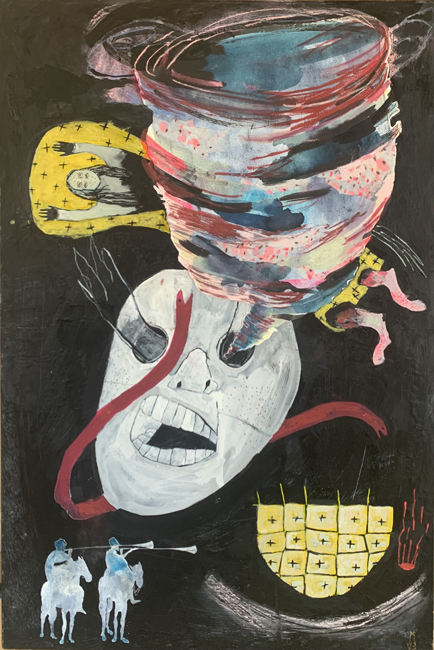

Park City, Utah-based Wren Ross traverses the liminal spaces of conscious and subconscious, body and mind. Her drawings, paintings, and prints often surround figures and characters with dreamlike symbols that are wrought from textural strokes of color. Her artworks, often bearing strange and enticing snapshots of fraught psycho-emotional states, also exude therapeutic properties.

During a recent home-studio visit, Ross—who’s a social worker in addition to an artist—unfurled the workings of her busybody creative engine, an ongoing corporeal expression of semiotic energy that she’ll show in a May 2023 show at Salt Lake City’s 801 Salon.

Her space is organized but host to many works-in-progress. A handful of paintings, surrounded by resources and materials, were stationed atop a work table. Talismanic sculptures and flowers formed an almost uncanny menagerie of characters beneath hung papel picado. Kraft paper rolls taped to the wall and floor indicated where Ross has focused her recent creative energy.

Ross takes inspiration from ancient artwork and nascent drawing traditions, such as the Cerne Abbas Giant and Korwa Indian drawings, respectively. She also studies children’s art—she was quick to share the book Analyzing Children’s Art by Rhoda Kellogg, which investigates the work of children artists from across the globe. Ross especially enjoys the “raw, intentional, deliberate, and earnest” line work and less-representational imagery often made by kids. For Ross, this allows a certain type of freedom and a shucking of the rigid traditions and methodologies of the western art canon.

“There’s something about the [ancient] artwork aesthetics and what happens in children’s art, which is this ability to transcend convention or expectation,” she says. “I think that we have an innate need… to make marks and to express our lived experience, and then to have it be static and stationary and out of the body… and be able to put it off to the side and to look at it.

“There’s something about conversing with yourself, about looking at what you’ve made—or looking at what your community has generated in terms of tropes that have survived over thousands of years or through many generations—as being frames of reference.”

As a social worker, Ross witnesses the therapeutic catharsis for young people when they can “dump their internal dialogue.” As a result, she considers art-making as an act of mindfulness and “a huge curative force for trauma,” she says. “Being in there and connecting with the tools, the colors, the textures, the sensation of using the tools and watching what happens, in some ways, isn’t satisfying at all if you’re not paying attention to it.”

After having children herself, Ross had less time to work away from home in a studio space, which galvanized her to “rearticulate and reimagine creative practice.” Ross created a new studio in her basement and now finds herself responding to sparks of inspiration between daily caregiving and tasks.

“The generative thing is having ideas, concepts, materials bubbling up and being like, ‘Okay, whatever needs to come up through me and wants to come through me and land on the table or the wall or whatever it is, I’m available for that, and I develop a relationship with it after.” This spontaneous approach allows Ross to occupy a more oracular role in her subject matter. She likens stewarding her pieces to being a social worker, where she serves in support of others.

Jarring, transfixing, anthropomorphic figures often agitate and torque Ross’s work—a midpoint between surrealism and expressionism.

“I think we can look at the way someone is holding themselves and get a good sense of what’s going on for them very generally,” Ross elucidates. “The figure is this very privileged visual element in a piece because it’s very specific… like, ‘I can tell that person is sitting down.’ So if everything else in the picture is nonrepresentational or really hard to understand or locate somehow, that’s either like a refuge or a resting point.”

These characters, their postures, and their situations often point to social and ecological ills. Those real-world phenomena snowball into narrative stills, almost like secular Stations of the Cross, which Ross divines in reverse by painting them. Whether they concern disastrous populist presidencies or the drying Great Salt Lake, her paintings evoke dreamlike relatability. Rather than wallowing in despair, however, the act of engaging with these paintings generates a shared bastion of endurance.

“Some days I feel like the small things make all the difference, and that’s enough. And sometimes I feel the opposite, like nothing you do can really help,” Ross contemplates. “I think many of us, I would say almost all of us, can relate to that feeling.”

Accordingly, Ross invites the viewer deeper into her worlds via her mark-making modalities. By accessing the kind of raw non-technique that nods to ancient and intergenerational artwork and children’s art, she vies to immerse the viewer within a lexicon of movement.

“There’s no way to authentically engage with this surface [when using art-making tools] that doesn’t have an energetic imprint,” she says. “Maybe that’s why we have comfort with the vocabulary in art critical theory of describing paintings as ‘violent’ or ‘being rooted in fear’… because I think that this is one of the few places where it’s difficult to be inauthentic.”

During a previous artist residency at Salt Lake City’s Modern West Fine Art, the gallery’s commercial angle necessitated that Ross make larger work. This adjustment gradually spurred her to access and leverage her background in dance. Today, Ross continues her exploration of the intersection between dance and painting while thrusting herself into yet more uncharted territory in preparation for her 801 Salon exhibition.

“The work for the show in May is in [the] process of making itself known,” she says. “The dance-rooted/somatic-experiencing concepts will be incorporated, certainly, though in what medium/form, I’m not certain. I’m also interested in the connection between movement, body, and mark, and so [I’ve] been experimenting with using torn drawings to make rope/cordage—[a] concrete/literal connection—which will show up in some form also.”