William T. Carson’s coal-based artworks comment on cultural relationships to fossil fuels and provoke questions about how humans value natural materials.

1.

I walk down several steps to William T. Carson’s Santa Fe area studio.

In the center of the room, a large piece of coal rests at the far end of two long wood planks. Coal stains the tops of the boards and drips down the legs of the sawhorses beneath them. Small black splatters cover the wood floor, stray flecks of mica, very little dust.

I ask if it’s okay to touch the coal, and William nods.

This type of coal is around sixty million years old. The texture is smooth, almost soft, against my fingers. The coal is a rich, matte black that leaves a thin dust on my skin. Subtle waves cover the surface of the rock.

William says he tries to approach coal the way he would approach any other material.

“I think it’s about assuming there’s intrinsic value in something, which to me, feels like a way of relating to the earth, a land ethic, or way of relating to landscape. What’s the inherent value? And starting to metabolize and understand there’s value in something just in its existence, rather than having to have an economic value.”

2.

William says he recently did a sound sculpture with this piece of coal.

“I was thinking we could pour some water on it today.”

He hands me a container full of water. I pour the liquid over the rock, and the studio is filled with the sound of fire. The water gently recedes into the coal, but the crackling continues.

“I had some geologists come to my studio at one point and they told me coal is hydrophilic.”

When coal is underground, it acts like a sponge and accumulates water (hydrophilic is a combination of the Greek words for water and love, hydro and philos).

“When the coal comes to the surface, it will dry out, so what you’re hearing is just the coal soaking in as much of that water as it can.”

3.

I look across the room at several small black tubs filled with coal of various sizes—from dust to pieces that could fit in both hands.

In earlier work, William arranged large pieces of coal into three-dimensional mosaics on wood panels. He says the practice taught him a lot about commitment, because he couldn’t move any of the stones once he placed them in mortar. He could only react with the next.

I tell William this constraint reminds me of contact improv: a dancer touches or brushes against another dancer, and that dancer responds to the contact with their next movement.

“Exactly. You have to stay in the moment and accept what you did a few moments ago. You can’t change anything.”

Before each of these mosaics, William sorted stones, prepared mortar, and sketched out multiple drafts of the composition.

“The preparation all led up to one moment where, if I was doing a large panel, in order for it all to adhere correctly and have a seamless appearance, I had to do the whole thing in one go. Sometimes it took twelve hours. That way of working felt a lot like a performance, actually.”

4.

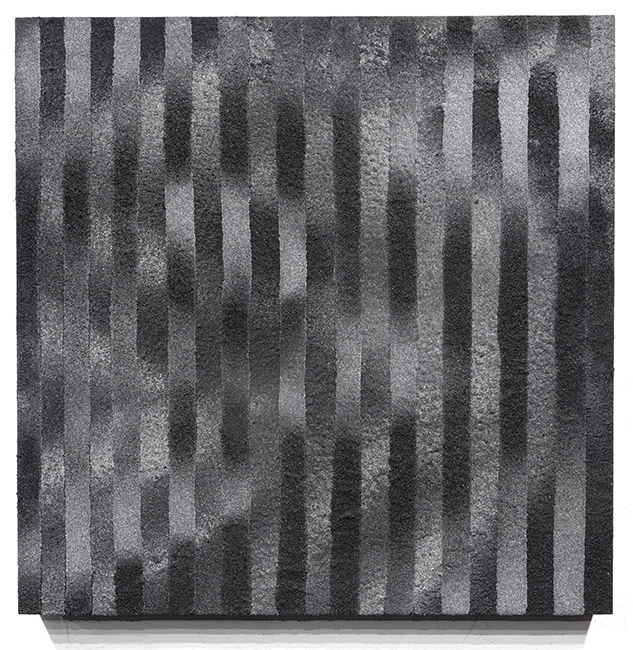

William and I walk over to five recent works composed of small fragments of coal and mica. In each piece, the dark and light appear to strike a different internal balance.

“I have powerful reactions to work that’s not aesthetically beautiful, but for me a lot of times, aesthetic beauty can draw me in and can buoy me up to look at some really harsh truths or ask questions… is this thing actually beautiful? Or can it be beautiful and corrupt?… if there’s something to fall in love with in a piece, it can pull you in and then show you things that maybe aren’t as beautiful.”

I look over at the pieces on the wall.

“It’s an inherently political act to make work with a fossil fuel and to make work with such a charged substance, but what I hope to do is make work that is spacious enough that someone has room to react to it, and make it their own, and figure out how they want to think about coal.”

5.

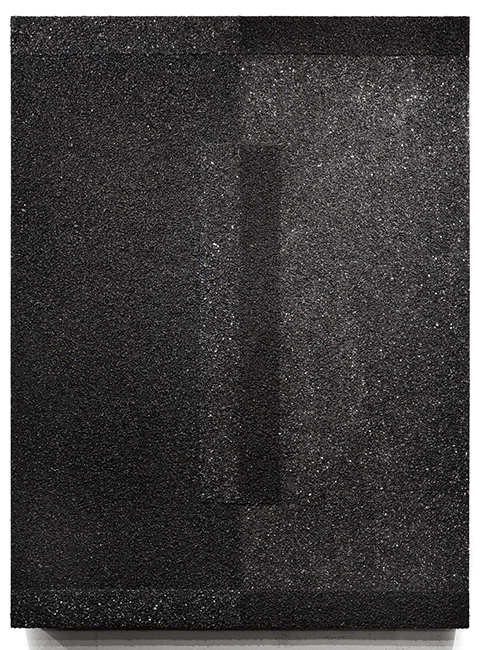

I think of a piece of William’s called Horizon.

Horizon is composed of small fragments of coal and gypsum on a thirty-six-by-forty-eight-inch wood panel. The top half is light with a dark horizontal line, the bottom half is dark with a light horizontal line. In between the two lines, the dark and light halves meet and create a third.

My eyes are always drawn to the third line. The horizontal lines above and below it look roughly straight, which emphasizes the subtle variations in the middle. It looks like the line is breathing.

William T. Carson was named one of Southwest Contemporary’s 12 New Mexico Artists to Know Now of 2020.