“How we relate to objects keeps me focused on sculpture, installation, and how we make meaning from the things around us,” Denver-area artist Trey Duvall says. But more than simply accepting an object’s purpose, Duvall looks for “opportunities where [he] can manipulate that meaning or understanding of what an object is and does.” Indeed, developing a working relationship with objects in order to fully explore their manifold—and, oftentimes, unexpected—meanings or uses drives his artistic practice and creative inquiries.

Born and raised in Durango, Colorado, Duvall now resides in Lakewood just outside of Denver. He returned to the state four years ago by way of Texas where he earned his MFA at the University of Houston and co-founded SITE Gallery, a unique art space that’s a cluster of decommissioned rice silos.

His current studio—a spacious garage transformed into a multi-disciplinary workshop—sits atop a rolling hillside next to an old horse stable with an expansive view of the Rocky Mountains. The sprawling space allows the artist to work on a variety of large-scale projects and experiment with ideas related to objecthood.

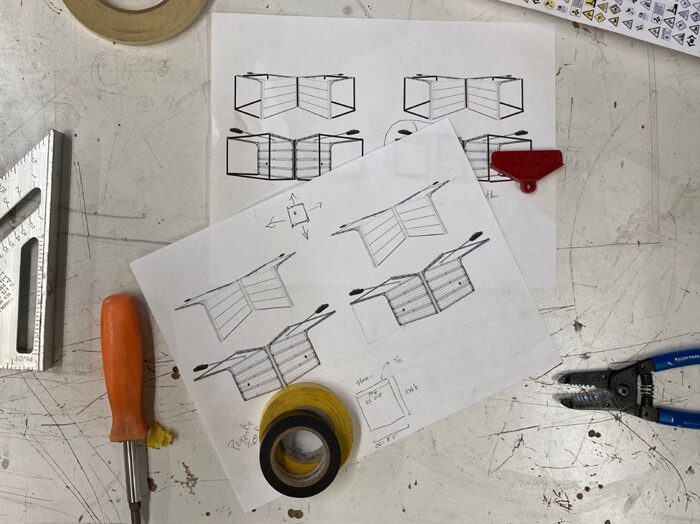

As you walk into the structure, you immediately notice a garage door system he constructed inside his studio adjacent to the building’s actual garage door. It’s part of a kinetic sculpture, titled form/re/form, which Duvall will debut at RedLine Contemporary Art Center on November 12, 2021. The installation will culminate in four garage doors arranged into a cube-shape and set to a predetermined sequence, opening and closing continuously at randomized intervals.

“Thinking about the quotidian object” through its uses and limitations, in the artist’s mind, is the primary conceptual driver of the project. Duvall fosters a palpable sense of the absurd by re-contextualizing garage doors in a novel arrangement within an art space. But he’s quick to note that “nothing is behaving in a way that is outside of its design.”

While their context has been altered, the garage doors still perform the task for which they were created. “I think a lot about the humor of objects and working with use and misuse,” Duvall says. “Misuse can point toward absurdity—there is humor in how we relate to objects and their language and the things that they come to represent. I’m looking for that humor.”

Absurdity through re-contextualizing an object isn’t Duvall’s only interest; he also finds an object’s inherent entropic qualities fascinating. “We all know garage doors,” Duvall says. “We all know that they fall off their tracks and they fail. And rattle. And get dented. To me, all those things are built into [it].”

An object’s uses and limitations are an overarching concern in most of the artist’s work. A recent installation titled Latent Variability in Axiomatic Structures consisted of three steel pipes suspended by cables from the ceiling of RedLine. The cables were programmed to lower and raise at particular intervals; as the pipes descended and contacted the concrete floor, they produced different resonances based upon their size, thickness, and angle of impact.

Latent Variability in Axiomatic Structures, 2020, RedLine Contemporary Art Center. Courtesy the artist.

Similarly, Duvall explores the human body as an object through minimalist video pieces. His series Do, Do, Do, Do, Do, which was showed at the University of Wyoming Art Museum in 2019, explored the “ergonomics of absurdity” that gestured “towards an abstract philosophical proposition.” Wearing a white jumpsuit and set against a white wall, Duvall and the artist Tiffany Matheson performed a series of repetitive and banal physical movements that framed the body as a mechanical object performing routine operations, which were destined to fail.

“Human-made [objects] are fallible. And where is that failure going to happen?” Duvall asks. An object’s failures are interesting to him because they exist within “its own internal logic, its own capabilities. Tires roll, ladders fall, [liquids] spill, and flammable things ignite.” Indeed, rolling, falling, spilling, and igniting can lead to failure; but failure, in and of itself, isn’t always interesting.

Of interesting failures, the artist explains, “If the materials are right. If the speed is right. If the duration is right, then when [an object] breaks down it’ll be interesting. If the individual variables, materials, people, motion, or space—if those are all aligned correctly, when it breaks or can’t [perform its function] anymore, when it fails, it’ll be interesting. If the system or construct breaks down because one of those variables wasn’t considered enough, that’s usually not interesting.” To this end, then, interesting failures usually relate to “stamina or duration”: when an object fulfills its “righteous motion and fails within that” over time. Such failures within this righteous motion can then lead to humor.

Humor, certainly, provides us with moments of levity that allow us to forget our daily routines and troubles. But Duvall understands its broader existential outcomes, which provoke fundamental questions about our lives. “What are we doing with our time? Is it meaningful?” he asks. “Those questions led me to [embrace] absurdity and futility. It’s a fundamental part of who we are and how we exist in the world.”

He couches his pursuit of absurdity and futility, though, within an affirmative and humanistic framework. “Believing that the things we do matter. The humor in that is wonderful. Especially given what we know more about our universe and our timeline. We can see our end, but we still operate and use language in a way that builds a more permanent world—a world that will outlast us. That’s humorous in the beautiful way. It’s a fundamentally human thing to do. I find it funny. And that’s behind almost all of this work.”

Trey Duvall, Do, Do, Do, Do, Do, 2019, University of Wyoming Art Museum. Courtesy the artist.