Colorado artist Terry Maker investigates the potential of discardable items—papers, markers, straws, even candy—by transforming them, through arduous processing, into ethereal yet witty wall reliefs and other objects.

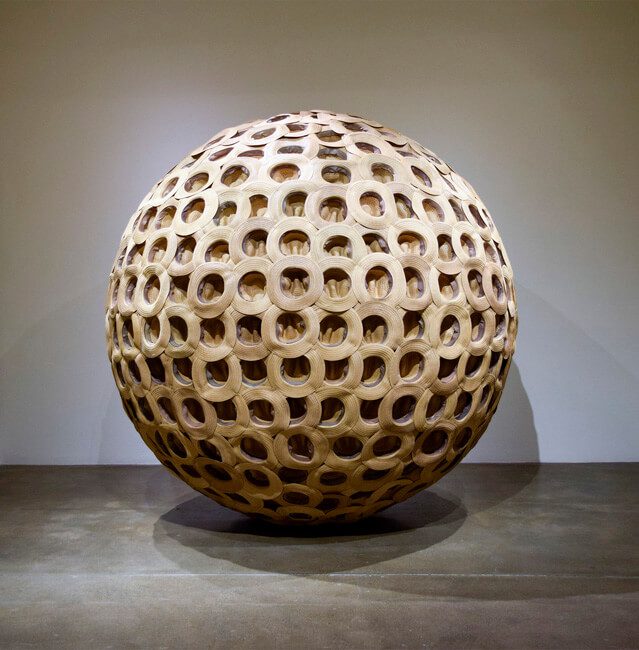

Her exhibitions over the years have made it clear that Colorado artist Terry Maker has an offbeat sense of humor. Take, for instance, Cowgirl Hat Ball, recently on view at the Longmont Museum. It’s a ten-foot-wide sphere composed of hundreds of overlapping straw cowgirl hats. Or Self-Portrait / How Many Licks Does It Take to Get to the Center, a six-foot-high replica of a cherry Tootsie Pop, accompanied by a video revealing that a cast of the artist’s head is hidden inside. The mixed-media sculpture is featured in her solo show currently on view through December 31, 2021, at Robischon Gallery in Denver.

It’s only by interviewing Maker and visiting her home and studio in Louisville, outside Boulder, that one comes to realize her artistic sensibilities come from a long journey—fraught with life’s ups and downs—toward self-knowledge, happiness, and attempting to understand the world. Humor has smoothed the process.

Amusing as it is, Cowgirl Hat Ball is, Maker says, “my feminist piece.” The hats are purposely positioned to show the underside of the brims and the inside of the hats, suggesting the power of female genitalia. Another take might be its exaggerated study of the geometric possibilities of cowgirl hats.

The giant Tootsie Pop is a conceptual piece meant to evoke not necessarily nostalgia, but to question the overbearing and sometimes racially insensitive ad campaigns for the candy in past decades. In these and other works, humor offers accessibility to Maker’s work, but it needn’t be the stopping point.

A tour of Maker’s home and adjacent studio reinforces the perception that she is introspective, highly observant of the world, and devoted to art in general. She has packed her living spaces with classic literature, thrift-store relics, and coffee-table books and art pieces by those she admires, including Tim Hawkinson, Gordon Matta-Clark, Sister Mary Corita Kent, and Louise Bourgeois. Funky touches are everywhere, along with trinkets paying homage to her native Texas.

Maker received art and education degrees in Texas before getting her MFA from the University of Colorado. Her career has included twenty years as an art professor in the Denver area, and her work has been shown in solo museum and gallery exhibitions throughout Colorado and the United States.

Maker shares the two-story freestanding studio, built two years ago, with her husband Chris Rogers, a photographer and robot builder. Her lower-level space catches the morning sun. It is spacious enough not only for art supplies, drawing tables, and works in progress, but also a couch and chairs, a desk, and more artists’ books. Her outdoor work areas contain an impressive assortment of tools, including a chainsaw and bandsaw, not to mention a lathe, drills, a belt sander, and a vacuum forming machine for encasing sculptural objects.

“Getting to the meat” is a phrase Maker often uses to describe her signature pieces—aggregations of castoff and discardable materials, heavily compacted and then reshaped into circles and other geometric forms. That’s where the saws come in, as she slices the aggregations into pieces, revealing their cross-sections and often surprising herself as to their aesthetic appeal.

A stunning example of Maker’s process is her Dust series, incorporating compacted scientific documents and pencils as well as jawbreakers, the classic candy, all embedded in graphite or resin. As the pieces become circular and square wall reliefs bearing candy-colored concentric circles, their ability to spark macro ideas about the cosmos or micro ideas about cell structure becomes beautifully apparent. The transformation is well-articulated in Maker’s artist statement for Because the World is Round (2020) at the Longmont Museum: the singular objects emerging from her process leave the viewer “free to discover the ways in which radical changes to material and presentation can reassign and revitalize meaning.”

Among the other materials that Maker salvages and re-envisions are straws, markers, medical documents, religious writings, vinyl records, prescription bottles, and woodblocks. After the items are amassed, sometimes by the thousands, and manipulated through slicing, shredding, grinding, scraping, and sanding, they shed their humble origins to radiate vibrant colors, detail, texture, and symmetry.

But “getting to the meat” could also be interpreted more broadly as getting to the core of things, especially as it concerns Maker’s quest for self-knowledge and for equanimity and balance in her life.

Maker says she’s the happiest she’s ever been, working full time as an artist. Yet she is candid about suffering from severe depression for many years until she found the right help—they were dark years in which Maker was unsure about her self-worth and self-identity, she says.

“I felt like, I’m gonna come and I’m gonna go, and I’m gonna be kind of cast off. I started thinking, ‘Let’s get to the very core of this feeling.’ And that’s when I started getting in and digging and cutting and rooting” with found and castoff materials, Maker says.

Her words strike close to being a metaphor for how everyone should examine life. And, in fact, Maker has spent many years on “an intense degree of inner investigation.” Fortunately for admirers of her work, it wasn’t at the expense of her sense of humor.