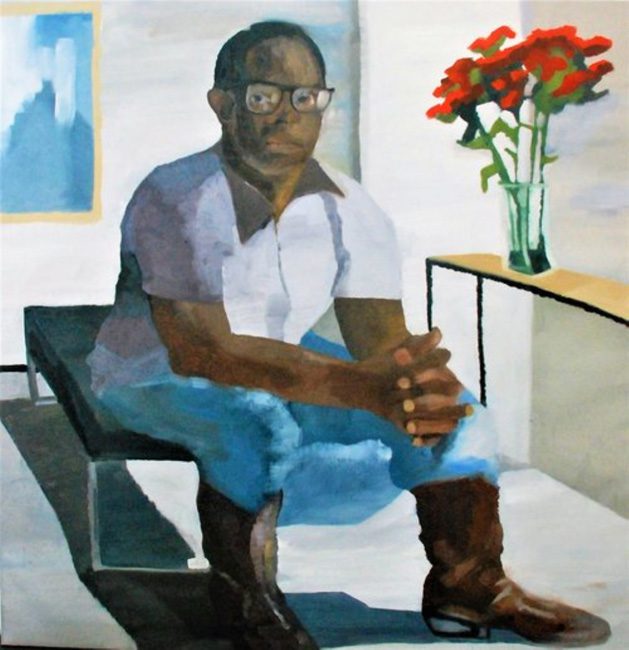

Rochelle Johnson, an artist in residence at Denver’s RedLine Contemporary Art Center, is a figurative oil painter who imbues her work with messages about women’s beauty, the Black community, and the human condition.

The nonprofit RedLine Contemporary Art Center in Denver is known as a place where emerging artists in residence blossom into established artists, and that appears to be the path for figurative painter and native Denverite Rochelle Johnson as her work gathers acclaim. As part of a small cohort of artists in two-year residencies, Johnson has turned her spacious RedLine studio into a creative space with finished and unfinished canvases propped against the walls. Worktables are overflowing with art books and sketches. On her easel is the start of a blue female figure with upraised arms suggesting praise, prayer, and spirituality.

Especially gaining attention these days is Johnson’s Blue World series of oil paintings showing nude women in repose, appearing almost as silhouettes floating on the surface of the canvas or caught in graceful movement. The contrast of blue skin tones with yellow, orange, and gold highlights adds to the women’s allure. Buoyed by the reception to the series, Johnson says she feels compelled to keep working on it as she finishes the second year of her residency.

Not only is Johnson’s star rising, but she continues to be a steady presence in Denver’s community of Black artists. Johnson is not alone in hoping the doors of Denver’s mainstream galleries open wider for artists of color exploring diverse subject matter.

In a hopeful sign, Johnson was featured prominently in the 2021 group show From This Day Forward at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art. The well-received exhibition centered on the havoc of 2020, with eight artists commenting on race relations, isolation during the pandemic, and our fraught relationship with technology.

Previously, Johnson has displayed her work at the McNichols Civic Center Building in downtown Denver. In 2017, she curated a group exhibition there called Inclusion: Diverse Voices of the Modern West. Other curation endeavors include the group show Daughters of Diaspora, which explored race and gender; it opened at the Art Center in Grand Junction, Colorado in 2018 and included several of Johnson’s pieces.

Johnson counts Lois Mailou Jones and Jacob Lawrence as two of her main influences, and she remembers in her younger days scouring an African American-themed bookstore for images that could inspire her.

She credits much of her aesthetic to living for many years in Five Points, a storied Black neighborhood in Denver and part of the Welton Street Historic District. Her Urban Life and Portrait of a City series from a few years ago—street scenes and portraits of Five Points residents—excel at capturing the area’s move toward gentrification and its cast of characters. They have a storytelling quality that continues to inform Johnson’s appeal as a painter.

Johnson’s art degree is from the Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design, and her later training includes classes from nationally known Black artist Ron Hicks of Denver. She credits Hicks for helping her push the boundaries of contrasting shades and the interplay of light and shadows.

Although Johnson spent most of the 1990s in Seattle working outside the art world, she returned to Denver with the goal of pursuing art more seriously. Although gallery representation in Denver has yet to happen for Johnson, the museum group exhibitions around Colorado have helped her make a name for herself. A few excerpts from a conversation in Johnson’s studio:

How has the experience at RedLine been?

It’s been great. I’ll be out of here in November [2022], but everybody’s been accommodating. I get to work at a scale much larger than in my home studio. And I just love the fact that this place exists, really, because once you get in, you’re part of the community.

You’ve mentioned that Blue World is getting recognized as your signature series. Could you give me a bit of background on the series’ origins?

The title comes from one of John Coltrane’s albums. My work started off talking about Black women in general, and how we’re marginalized, but now it’s also become an affirmation for myself. The color blue is an uplifting color, associated with wisdom, loyalty, strength, spirituality—all these great universal attributes.

I remember a painting at BMoCA called Repose, which not only speaks to women’s beauty, but also the need for self-reflection. Do you agree?

Repose was one of a series of paintings I made about the time of the George Floyd murder, and it’s a reflection of how tired I was with what was happening in the world, especially to Black people, let alone this long period of sheltering in place because of the pandemic. I had to gather myself and rest, before I could move on.

Would you say that Blue World has things to say about women’s problematic relationship with body image?

It’s really not about body image, it’s about skin color. I feel that if people can come to my paintings without the notion of, oh, it’s a Black person, then they’ll realize it can stand on its own merit. Maybe that would help do away with the construct of race, and we would become closer to showing our humanity.

Do you have any shows coming up?

Not right now. I’m creating a body of work so that I can shop it around to galleries and museums. I’m trying to get onto the path of doing more museum shows. I think the galleries will come, eventually, maybe here in Denver, maybe outside of Denver.