Betelhem Makonnen of Austin expands the silences of history and develops work and language to describe nonlinear time.

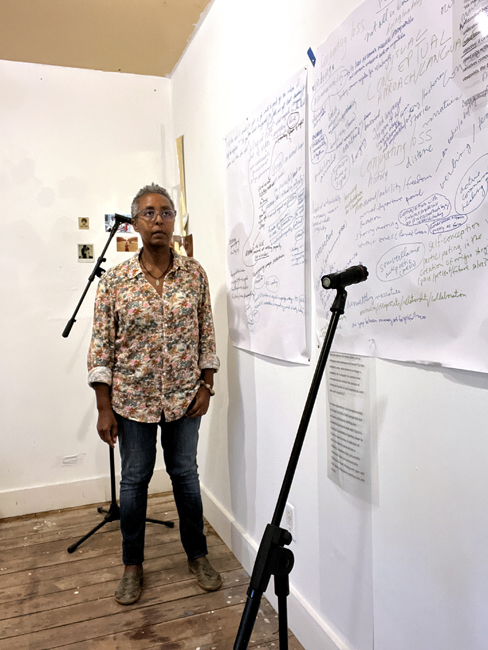

To get to artist Betelhem Makonnen’s studio, I walk through a gravel parking lot surrounded on two sides by ivy and trees that grow into a chain-link fence. Corrugated metal and planks of wood are stitched together to make a warehouse that holds studios, an exhibition space, and a stage for theater, music, and an annual holiday musical theater extravaganza. The glare of a developer’s property next door hurts my eyes when I look in its direction, but upon entering the Museum of Human Achievement, the aged wood and paint speckled floors offer a warm refuge.

Makonnen’s choice of place for her studio embodies a congruity. Makonnen and MOHA both engage in a hard-to-find level of art- and community-making that I seek in order to survive. Both artist and venue emit a genuine steadfast nature around what it is to seek beauty and understanding in a violent world.

Born in Ethiopia, Makonnen currently lives and works in Austin. She received an MFA from the School of Art Institute of Chicago and has exhibited at the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Le Musée des Abattoirs in Toulouse, France, the George Washington Carver Museum and Cultural Center in Austin, and The Contemporary Austin. Makonnen co-organizes the Addis Video Art Festival, a city-wide annual screening of digital media in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. She is also a co-founding member of Black Mountain Project, a contemporary art platform that presents exhibitions and performances.

Through installations often involving large scale prints and video, Makonnen brings attention to the time compressed by images and objects. She pinpoints moments that escape between words and expands them. Time and the unrecorded become mediums in her hands.

“I make work thinking within duration, a time-space that you can enter into rather than,” Makonnen snaps her fingers, “a captured moment that you’re looking at, removed from it. Trying to communicate time as we experience it. I don’t think it’s some line that we’re outside of, that is happening objectively. Time is something we’re in and within it. We are moving with our thoughts, just like me and you talking now.

“We’re going into the 1970s, we were just in the 1980s, and we’re sitting here in 2023. That is how we experience it. Every day time travel,” says Makonnen. “We constantly insist its fixed points that are successive one after another when nothing in our life communicates that.”

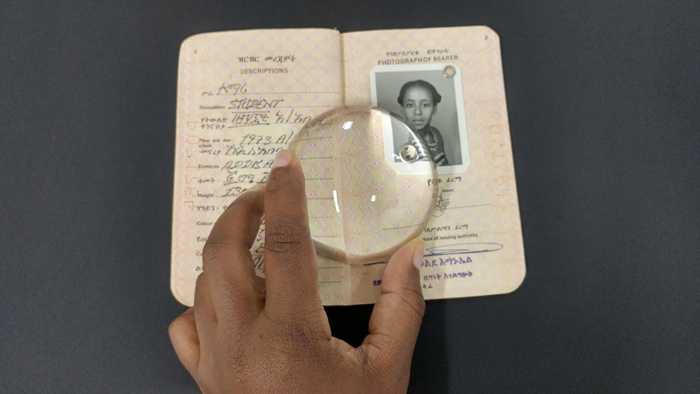

In her 2019 two-person exhibition the meaning wavers with Stephanie Concepcion Ramirez at Austin’s Women and Their Work Gallery, both artists probed their personal and family history around “immigration, transnational identity, and the impact of silence on our perception of history.” For Makonnen, telling what is in those silences is about retelling history to reshape who we are now and in the future.

“I keep thinking about a blink,” Makonnen says. “All the history that happens in the blink of an eye, in the darkness and the light. We blink to see better. A blink is a momentary blindness that opens up sight. Or like a squint. I squint to see better. Somewhere where the darkness and the light are together.”

In her 2022 Artpace San Antonio exhibition unsettling narratives, the installation figures at sea (a ruttier* for unsettling narratives in diasporic time, again and again, future/present/past selves) includes a print of Makonnen and her younger brother at the beach that covered a wall from floor to ceiling. Their two bodies are tense with captured movement as a wave breaks. In the distance of the image is a faint sailboat. At Artpace, sand was spread from the wall out to the viewer. Around a pillar in the room, a sandpile was topped with a toy boat that echoed the boat in the photograph. The installation blurred the lines between what is in the image and what is around the viewer, as if one could step through time and back into the photograph.

Makonnen unpins the original photo from her studio wall and places it between us. Its smaller size reminds me of older photographs from the 1980s and 1990s. It’s faded, and I’m afraid to touch it. I react like I’m in a sterile museum, but her studio is a workspace.

Writing utensils are in a row on the folding table that is her desk. Old cameras sit on the bookshelf behind her. The books are categorized by color because Makonnen finds them by their spines, not their titles or editors. Objects are meant to be touched and turned in the light.

Makonnen draws my attention back to the image and explains how her older brother gave her this family photograph, and how she had never seen it before. As she describes the image, time slows for me. I remember then the rare feeling of what it’s like to be transported by art, to look closely, take it in gently, and lose myself in it.

“It’s an arrival. It’s a departure. It’s a shoring, a mooring. The size of the bodies and their stance. I thought, oh wow, that’s my whole life as a diasporan. A constant negotiation,” Makonnen says. “And it has a sublime factor to it, too, as in beyond comprehension. Nature that big and then the fact there’s this little ship in the horizon, barely there, and the figures are turned looking towards it.”

The past three years have been difficult for Makonnen. The pandemic and racial injustice have taken their toll on top of a battle with cancer and the passing of her mother. She is intentionally figuring out how she wants to be in this world after such ruptures. What and why does one do what ones does in the short span of a human life?

“More and more I feel myself pulling away from abstraction and its inherent association with removal and separation,” Makonnen describes. “Its linguistic root. I want to work within a language of combinations and simultaneity that communicates living, because living implies change and movement. So that’s what I’ve been thinking about. Conjugating loss. Conjugating the history of a blink of the eye. How do you make it durational, how do you acknowledge the time in it?”

Like learning a new language, as I talk to Makonnen, I feel understanding wash over me for a moment. For an instant, I get it. I can conjugate the verb without thinking. In the next moment, I stumble. I get caught in the barriers I’ve been taught. I forget a word or remember it in another language altogether. And then I look again. I let the subtle change of light and the assemblage of concepts Makonnen has brought together help me see.