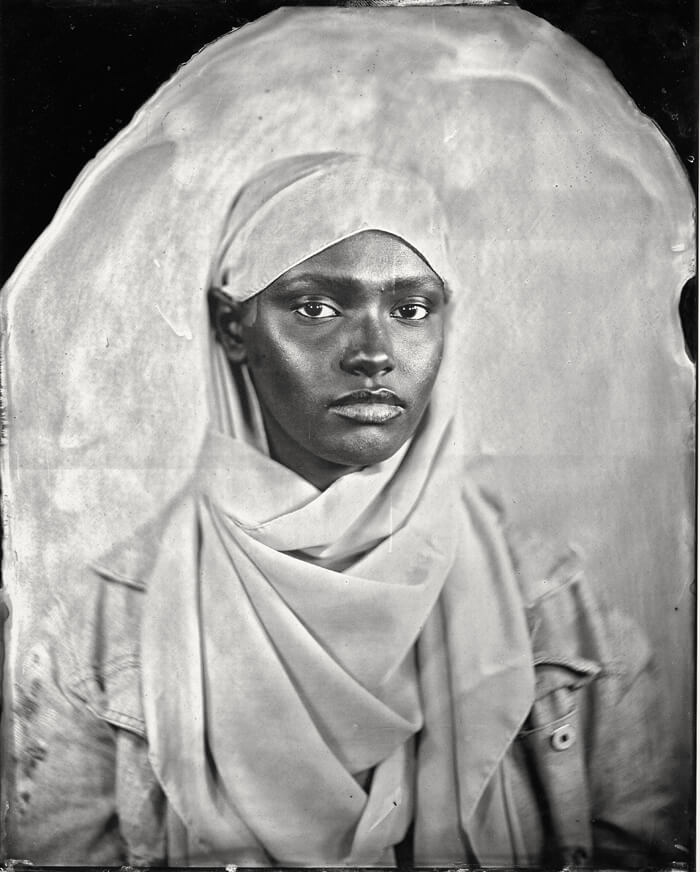

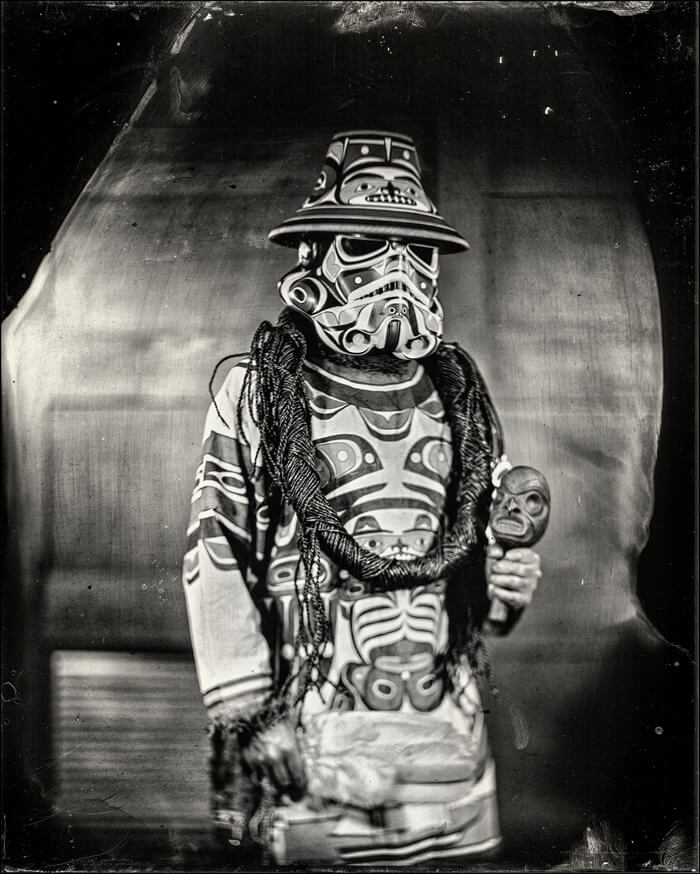

Will Wilson is a Santa Fe–based photographer and educator. He is chair of the photography department at the Santa Fe Community College and is working on several ongoing projects. Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX) and Talking Tintypes both utilize wet collodion printing and began as a response to the portraits of Edward Curtis, who produced The North American Indian, a body of work from the early 1900s that continues to have an impact on Native American representation today. “I want to supplant Curtis’s settler gaze and the remarkable body of ethnographic material he compiled with a contemporary vision of Native North America,” says Wilson.

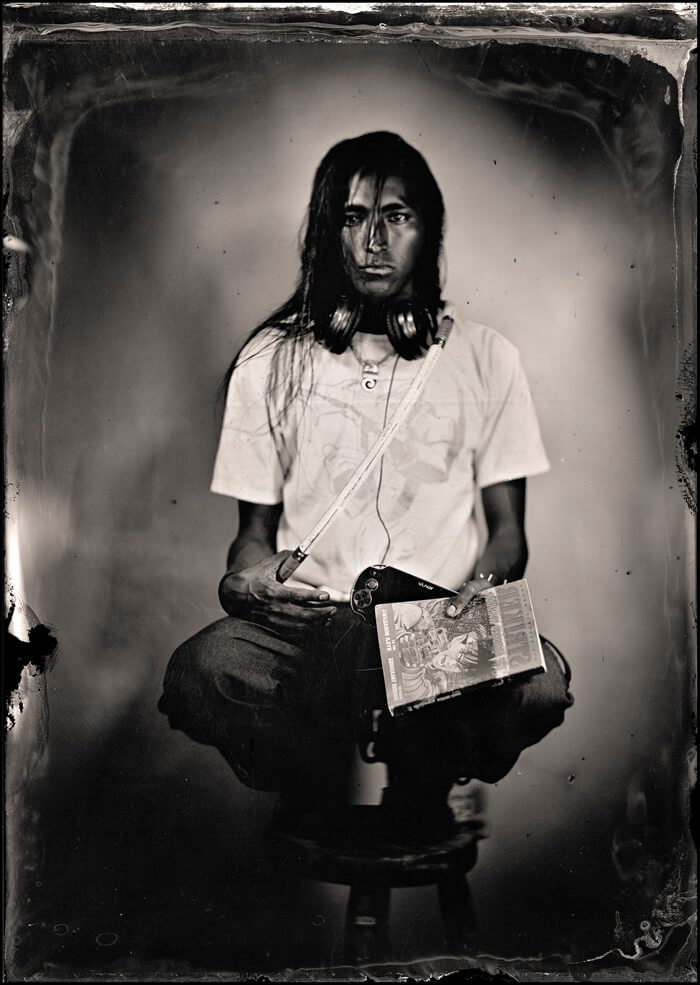

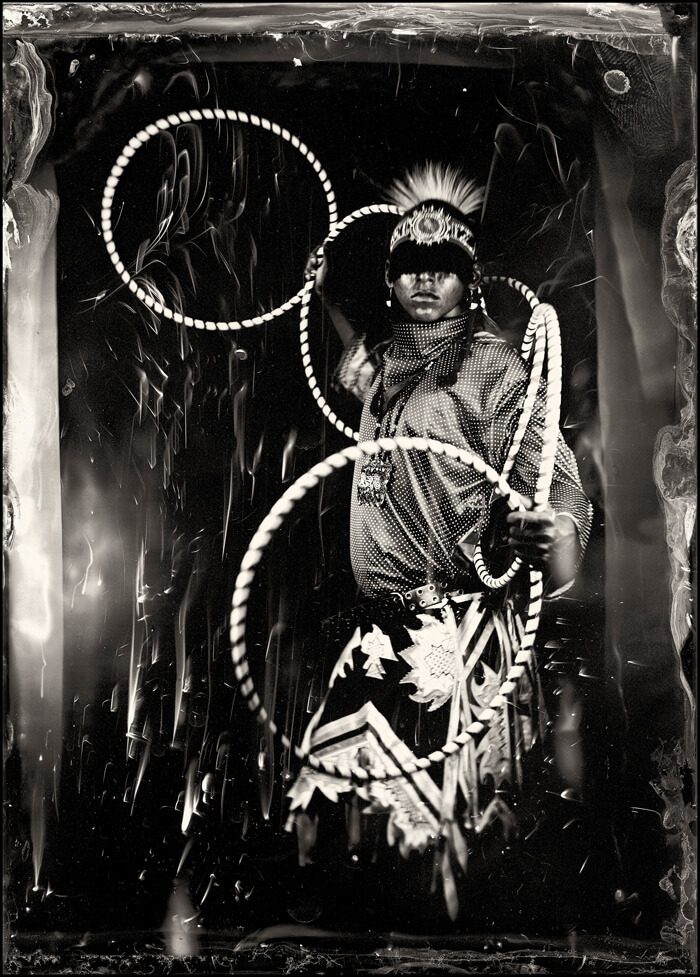

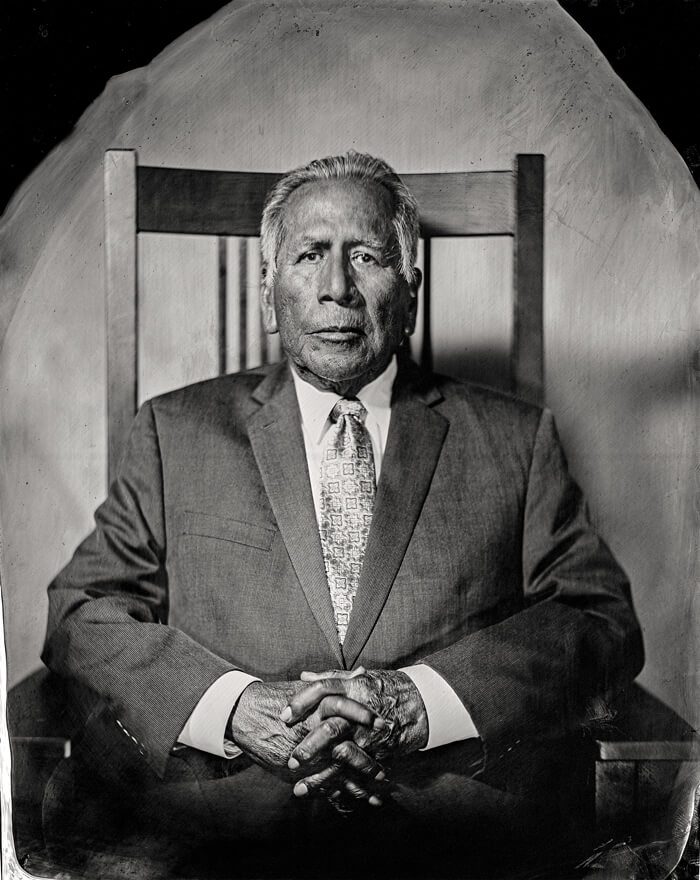

Wilson began CIPX in 2012 with the support of the New Mexico Museum of Art and has photographed internationally, adding to the prolific body of work. Over time, the project and Wilson’s intentions have evolved. Today, he speaks about the ritual of portraiture and questions how it fits into contemporary culture. Some traditions that were once a rite of passage for families and individuals have become part of the past. Wilson’s process is collaborative and allows his subjects to have an equal say in their representation. Many of the subjects bring props or carefully consider their pose for the image to illustrate their identity. Talking Tintypes, a progression of CIPX, takes the idea of collaboration one step further by integrating augmented reality technology into the project, which allows the viewer to scan a QR code and watch a video clip of the subject in motion.

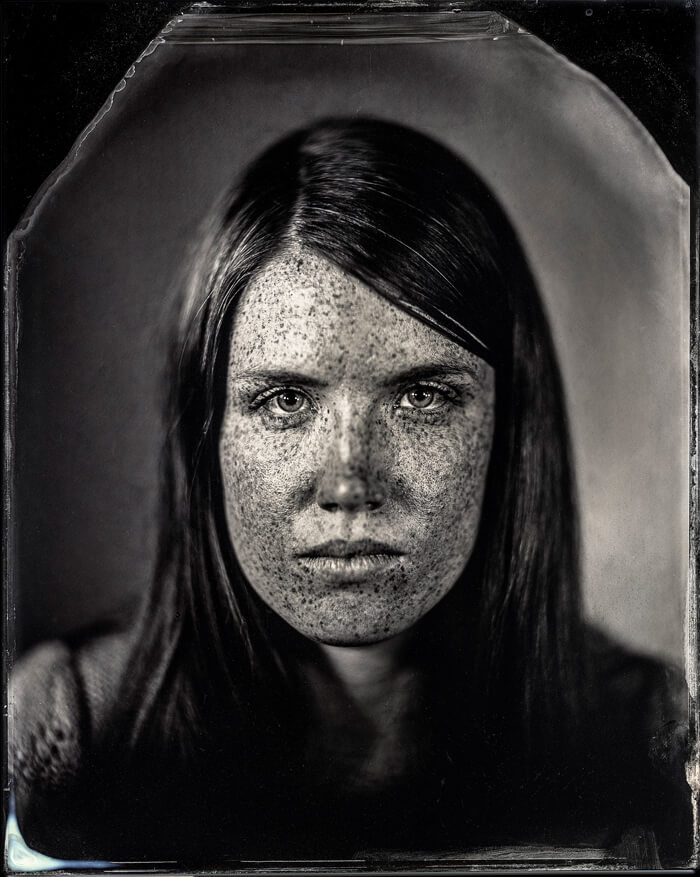

The Diné artist feels it is important to photograph with the wet collodion process for two reasons: it is a medium that references a historical period associated with Native American imagery, and it is slow. It takes time to prepare the glass plates, mix chemistry, and assemble sets. The ritual of portraiture becomes an “Indigenous experience,” according to Wilson. From a viewer’s perspective, the use of this historic medium is rooted in time and its passage. Despite what props, fashions, or eyeglasses a subject wears, the prints feel culled from the nineteenth century.

In Curtis’s images, the subjects fulfilled the vision and agenda of the photographer. The subjects of Wilson’s images have agency. The process and medium inspire both viewer and subject to think more deeply about their own representation at a time when photographic representation is often an extension of being. What does it mean to sit still in front of a camera? To live with your likeness embodied as an object? Perhaps Wilson’s images are the beginning of a dialogue that will slow people down and consider what their image means.