The movie Faces Places, considered a masterpiece by many contemporary film critics, won Best Documentary at Cannes in 2017. It was written by the esteemed French filmmaker Agnès Varda and was directed by her and the French artist-activist JR. Faces Places has been enthusiastically received for the surprising and lively collaboration between the eighty-eight year old Varda—one of the original members of the French New Wave—and the thirty-three year old JR who goes only by his initials. In fact, Varda is considered to have made the first New Wave film, La Pointe Courte, in 1954, preceding Jean Luc Godard’s Breathless by six years. She also made the highly regarded movies Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962) and Vagabond (1985), the latter becoming an international success. Along with Godard, Varda was part of the Left Bank avant garde that also included her late husband Jacques Demy who made The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964).

Thinking about how Varda, nearing the end of her life, came together with the prolific photographer JR to make this unconventional French bouillabaisse of a road movie—also a love story in its own idiosyncratic way—I wondered if one of the reasons she was drawn to the young artist was because the charismatic and telegenic JR reminded her of Godard when he was young. Indeed, there is an uncanny resemblance between the two men even down to their cleft chins. And how deftly Faces Places weaves together elements of Varda’s long career, along with snippets of New Wave history, into the fascinating adventures of two unusual individuals as they banter about life and art in a studio on wheels. Almost like magic, they meet the perfect subjects for their photographic project in the French countryside, at the port of Le Havre, or in a nearly deserted old mining town with its once thriving district of workers’ row houses.

So subtly complex is this movie that it would take many viewings to sort out all the loopings, longings, and references, and then there is the sly way that JR and Varda have with each other—each artist a kind of trickster figure as the multiple braids of their relationship are formed, intensify, and come to life in all their charm, warmth, and virtuosity.

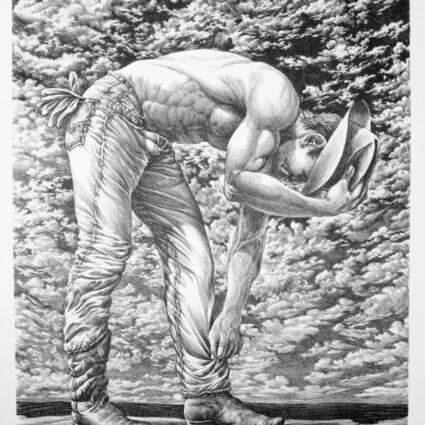

JR has a large van that functions as his photography studio and printing facility for the very large black-and-white images that get pieced together and then pasted in various places—on factory walls, a water tower, a barn, an old brick building in a small urban center, and tanker cars on a railway. In The New Yorker, film critic Richard Brody recently wrote that Faces Places “is about the heroism of daily life—it’s a trans-ideological vision of curiosity, empathy, and dignity.” If that sounds a little pollyanna-ish, the movie quickly displaces any saccharine overtones with the sheer virtuosity of JR’s print-and-paste portraits of, for example, a farmer, a mailman, a waitress, an aging woman who refuses to move from the miner’s house where she was born and raised, plus a goat and some fish. Varda and JR meet the woman who won’t move, listen to her story, and then take her picture. One morning she leaves her house and sees that her face has become façade and now covers the whole side of the building; she is stunned and so are we. In each encounter, a portrait is made and attached to a building or a wall. They are not always single portraits—there are group images too, like the factory workers at a hydrochloric acid plant who are cleverly positioned as two large ensembles with their arms raised and as if leaning against each other. There is an embodiment that happens between image and surface that renders the portraits almost supernatural in their overwhelming sense of presence and the visual poetry of their realness.

Brody also went on to write that “the film’s subjects are turned into public figures, subjects of art and media discussion.” Although Faces Places is a whirlwind ride through ideas about contemporary art, film, and the working class, its humorous one liners and easygoing back-and-forth dialogue between Varda and JR almost undercut the deeply poignant meditation that is at the heart of the movie: Varda’s interior gaze into the landscape that represents the final chapter of her life and her quirky search for signifiers of mortality. And that’s why it was particularly satisfying to have JR choose one of Varda’s own photographs, from a much earlier phase of her life, as part of the whole project that comprises Faces Places. JR selects a portrait of the late photographer Guy Bourdain, that Varda took when Bourdain was a young man, and JR and his assistants attach it to the side of a German bunker from WWII—one that had fallen over a cliff onto a beach on the Atlantic coast of France, a huge concrete square that bizarrely landed on its corner. This episode becomes one of the most memorable and gripping segments in this quixotic documentary.

So subtly complex is this movie that it would take many viewings to sort out all the loopings, longings, and references, and then there is the sly way that JR and Varda have with each other—each artist a kind of trickster figure as the multiple braids of their relationship are formed, intensify, and come to life in all their charm, warmth, and virtuosity.