Tina Mion ventures into unexplored territory in her exhibition Departures through death spoon sculptures and paintings about her brother’s death.

Tina Mion: Departures

August 2–September 7, 2024

Kouri + Corrao Gallery, Santa Fe

Content warning: This review addresses suicide, gun violence, and childhood abuse.

No one is exempt. All earthly creatures are mortal, each existing moment to moment in exquisite balance between life and death. Most days, such thoughts go unconsidered. We have stuff to do, people to take care of, art to make. When Sedona-based artist Tina Mion is drawing, painting, or fabricating a sculpture, however, she’s acutely aware of the liminality in the day-to-day. Death is always foremost in her mind.

No wonder: born in Washington D.C. in 1960, Mion was four when her family moved into an abandoned mortuary in New Jersey. She has spoken of the place’s gruesomeness (things in jars, bloodstained curtains), as well as of the neglect and abuse she endured. During her childhood, her mother attempted suicide several times and was committed. Her brother, Russell, was sickly, often toddling around on his tiptoes in dirty pink footy pajamas, she told me. On his twelfth birthday, their stepfather gave Russell a gun, despite the boy’s mental instability and emotional outbursts. In 2018, the adult Russell suicided with a gun.

Mion’s work has often (not always) dealt with extreme, even triggering subject matter, perhaps mostly famously in her massive painting A New Year’s Party in Purgatory for Suicides (2004), which hangs in the library at La Posada, the Winslow, Arizona hotel she owns with her husband Allan Affeldt. The work features seventy-seven famous victims and people Mion has known—with herself painted in a corner. Mion’s posters and paintings of her wildly imaginative Spectacular Death Spoons are another example.

At once ghastly and hilarious, these and other Mion works juxtapose history, politics, and Mion’s lexicon of iconography (precariously balanced elephants, herself as a clown, frosted pink cakes, flaming candles, moths, paintbrushes, the dusty-pink to oceanic-azure of the Colorado Plateau horizon, piñatas) in ways that offend, amuse, stun, resonate, and mesmerize. Often simultaneously. Her current exhibition Departures, on view through September 7 at Kouri + Corrao Gallery in Santa Fe, treads this familiar territory while venturing into heretofore unexplored personal and professional domains.

First, Mion has materialized several of her death spoons into bronzed and oil-glazed sculptures, some almost four feet high: a pink cake sculpted in reference to a famous French monarch’s beheading replete with guillotine (Spectacular Death Spoon Marie Antoinette) (all works in the exhibition dated 2024); an elephant holding a used paintbrush and sitting on clown boots atop a fractured bronzed femur with the bowl of the spoon holding the artist’s tombstone (Spectacular Death Spoon Self-Portrait with Elephant). Mion’s first venture into sculpture is accompanied by delicate watercolor studies for these and future works framed in black on the pink walls of the gallery’s first room.

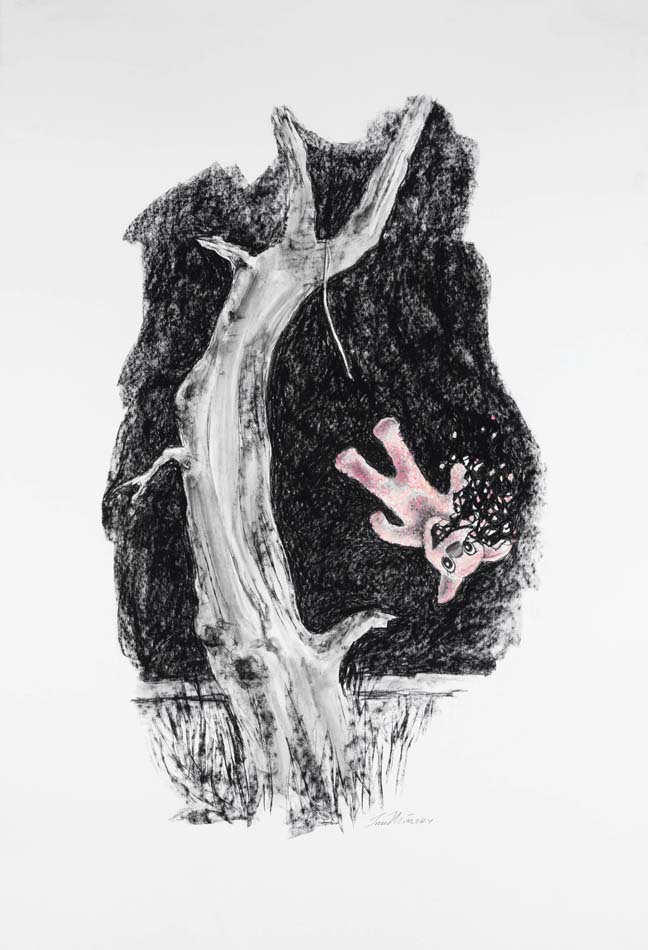

Second, Mion has addressed her brother’s suicide, with an oil-painted diptych in which a cartoon-bunny piñata—pink, white, dirty—with a big mouth and black eyes holds or releases a pistol while hanging or flying from a dead tree. The diptych occupies an entire wall in the gallery’s larger space. Nearby are charcoal-and-pastel drawings of the diptych that portray the suicidal piñata in various stages of hanging upright, falling upside-down, and dissembling.

“’Pignatta’—Italian for ‘fragile pot’—was a game played with a clay pot by Roman soldiers, a precursor to our modern piñatas,” Mion writes in a statement of work for the exhibition. “My Piñata paintings explore our lives as fragile pots—filled by experience; worn, altered, and ultimately taken by time. I use piñatas in my work to emphasize the tenuous and fragile nature of our existence.”

In casting her brother as a child’s plaything traditionally undone by violence (whacks from a stick or bat), whose wide-eyed, goofy expression never changes, even as bits explode from its mouth, is Mion softening the blow? Introducing the absurd? Being surreal? In the uncanny valley of Mion’s psyche, interpretation depends on your sensibility.

The exhibition also includes oil-and-acrylic paintings in elaborate oval frames and simply framed charcoal drawings of moths flying near candle flames, their wings trailing smoke. “I hate fire, yet I paint it,” Mion says in her statement of work. “[T]he smoke rises like signals or veils, dispersing its secrets; it’s all about the smoke, not the moth, not the flame.”

All about the in-between-ness, in other words, of before and after: the liminality of existence. These themes reach conflagration in the painting Finality of Fire, with a burnt moth lying atop an elaborately “frosted” cake, and in the drawing Piñata with Fire, in which the bunny piñata with stomach open to a blackened unknown, holds a pistol in one hand, its other hand in flames.

As a species, humans seemingly have an insatiable desire for self-immolation. We drink and drive, abuse drugs, gift children firearms, ignore and even deny the consequences of climate change. Departures, perhaps in spite of its subject matter, exhibits miraculous joie de vivre: Mion unflinchingly delves into darkness, emerging with work singular in its guilelessness and reflecting a sensibility uniquely her own.