A survey of Utah’s public monuments and architecture reveals devotion to the LDS faith, but various prominent examples of resistance to this narrative abound.

Upon entering the Salt Lake Valley in the summer of 1847 after a harrowing cross-country journey, then-prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Brigham Young surveyed the vast desert terrain that would become the Saints’ headquarters and famously uttered, “This is the place!”

Since then, the LDS majority in Utah has used public art and monuments to tell a distinct story of a religiously persecuted minority aiming to solidify their own cultural identity through the visual realm. This narrative cultivated an idea of the pioneers as founders of a religious Zion even though the region was already home to several Indigenous tribes, and today is expanding in ethnic and religious affiliations outside of this limited demographic. Yet, from the mid-19th century onward, Salt Lake City has used public art to perpetuate and solidify the cultural hegemony of the white majority.

Monuments to a new American faith

The region the LDS pioneers anointed Deseret was Mexican territory at the time of their arrival in 1847. Settlement of the region could not have occurred without drastic displacement of and violence toward the region’s Indigenous peoples, who went from living across all of present-day Utah’s land mass to “4 percent of the land base within sixty years of the Latter-Day Saint arrival,” according to Professor Paul Reeve, chair of Mormon studies at the University of Utah.1

The creation of the Salt Lake Temple was among their first and most significant efforts. Brigham Young set aside the site for this most magnificent symbol of the Saints’ resilience a mere four days after their arrival, setting in motion a forty-year project to construct what would eventually become a 222-foot pristine structure composed of white granite mined from nearby quarries. From the beginning, the temple’s allure was evident in several respects, among them its architectural splendor. The temple’s neo-Gothic design incorporates the signature pointed arches accentuated by a façade flanked by three vertical towers—reminiscent of iconic medieval forbears and a marked attempt to place the Saints’ new Zion into a broader world lineage.2

Meanwhile, as the LDS faithful were constructing the temple, nearby Freemasons were designing the Salt Lake City and County Building, a notable example of Romanesque-revival architecture. Constructed from 1891 to 1894, the City and County Building’s designers modeled its façade to mimic the three spires of the LDS Temple. This stylistic similarity is noteworthy given the rumors that its designers envisioned it as a secular rival to the LDS Temple amid years of political battles between the LDS-dominated People’s Party and the dissident Liberal Party that formed in 1870 to resist LDS religious and economic domination.

In front of the plaza that houses the iconic structure is Temple Square, a ten-acre ornamental site of reverence for the LDS faith, replete with a visitor’s center and lush tulip gardens in the spring and wondrous light arrangements during the holiday season. Cyrus Dallin, a Utah-born sculptor, crafted a monument to Brigham Young that stands at the south entrance to Temple Square. Dallin famously fought with the Brigham Young Memorial Association over his creative vision for the work for years.3

The sculpture features Young atop a tall vertical pedestal, his left hand gesturing outward at the desert landscape where his Saints would rest after their exhausting journey to religious freedom. The sculpture’s base features an intricate low-relief section depicting a man, woman, and child in front of a covered wagon as homage to the pilgrimage. Sculpted figures are featured in seated positions on each side of the base. One is a fur trapper, an embodiment of the pre-LDS white explorers who traversed the area, while on the other side is an Indigenous figure. While recent scholarship has highlighted Dallin’s apparent activism for Indigenous rights, the formal arrangement of his Brigham Young Monument clearly places Young at the apex of a historical hierarchy.4 His presence at the top of the structure looms above the other figures as if they are relegated to the region’s past and not an ongoing part of the future. Here, the notion that Dallin’s mere recognition of Indigenous existence is a form of activism ignores the ways in which this presentation of non-white figures repeats stereotypes common to public monuments, presenting them at best as mere observers to their own destruction and at worst, obstacles necessary to overcome for Euro-American freedom to take full effect.5

A monument constructed decades later—Millard Malin’s Sugarhouse Pioneer Monument (1930)—takes visual cues from Dallin’s Brigham Young Monument, featuring a tall obelisk with two figures on either side, their backs to the tall structure.6 Commissioned during the Great Depression, the work celebrates the communal efforts of manufacturing from the pioneers to present. The monument depicts two Indigenous figures in low relief on either side of the top of the obelisk. One is depicted carrying weapons of war, while the other holds a peace pipe. Malin described them as “representing the passing of the red man.”7 Both Malin and Dallin’s monuments recognize Indigenous identity as a precursor to rather than concurrent with pioneer prosperity. Malin’s obelisk also features representation of the beet mill, a fur trapper (another Dallin similarity), and a Greco-Roman-inspired female figure surrounded by drapery and fruit, a symbol of the lush fertility of the Salt Lake Valley. In perhaps an unintended way, this figure is a subversive signal of the Western colonialism that made settlement of the region possible.

Resistance to the predominant narrative

While Salt Lake City is replete with monuments paying homage to religious martyrdom, in recent years public art has been used as a passionate vehicle for asserting identities outside the white, LDS demographic. These works demonstrate that the region is also home to people of color, women activists, and one of the nation’s largest LGBTQ populations.

Recently, murals have become a vital part of community development, especially in areas formerly denigrated as undesirable because of their lack of proximity to Salt Lake’s highly gentrified downtown. Suburbs such as South Salt Lake City and West Valley pair murals with development grants to fuel economic and residential interest in their cities.8

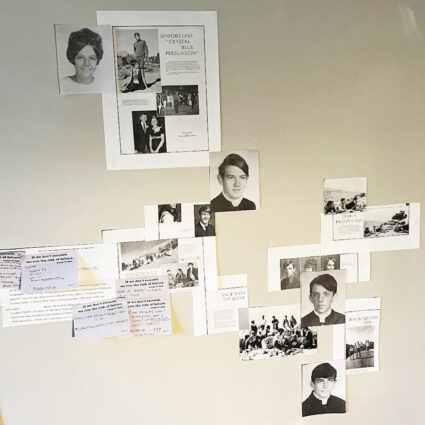

Public murals are also among the most democratic vehicles for affirming identities outside the predominant culture, sidestepping the state-sponsored bureaucratic hurdles of erecting permanent public monuments. Among the most beloved and recognizable is Jann Haworth’s SLC Pepper (2004), an homage to notable figures both local and international. The work recalls the style of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1969), the design of which Haworth co-created with her then-husband, British Pop artist Peter Blake. In 2020, Haworth directed the creation of the Women’s Mural, which pays homage to feminist heroes and regional figures to commemorate the centennial of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, which guaranteed women’s suffrage.9

In areas outside Salt Lake City’s downtown, murals have become sites of communal gathering and activism, honoring the lives of those killed by police and bringing attention to the ongoing epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. Elsewhere, murals commemorate the contributions of Black women to the state’s history and show the possibility of Utah as home to a more diverse worldview.

In the immediate aftermath of the death of George Floyd and subsequent mass civil rights protests in 2020, portraits of individuals killed by police began appearing on the edifice of a large structure on Salt Lake City’s Fleet Block. West of the city center in a largely industrial area, this region has undergone massive change in recent years. As Salt Lake City has recently announced plans to rezone the area, public outcry has focused on the portraits as a vital site of community gathering and mourning.

In late spring 2022, the Urban Indian Center of Salt Lake and Restoring Ancestral Winds—two grassroots, Indigenous-led community organizations aimed at raising awareness of the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls—debuted a mural within a community healing garden highlighting this tragedy. In addition, last year, West Valley became home to a large mural by artist Bill Louis. Where we Belong depicts the artist’s niece gazing out toward a multifaceted crystal-ball shape containing images of Salt Lake City past and present. Of this work Louis states, “she represents the growing diversity and the future generations of people of color who have moved here and made it their home.”10 Another mural depicting four Black women who have contributed to Utah’s history is planned for Richmond Park in Salt Lake City.11 While it’s significant that such murals are located within the more diverse communities fueling their creation, this furthers the pre-existing relegation of divergent voices outside of a so-called city center.

At 4.7 percent of the total metropolitan population, Salt Lake City’s is among the nation’s largest LGBTQ populations in the United States, and some public art reflects this reality. In the summer of 2019, artist Josh Schuerman debuted a large-scale mural of Harvey Milk on the eponymous boulevard, named in 2016 after the pioneering gay rights icon. Just this year, a large whale sculpture also appeared at a traffic roundabout on the beloved street. The work by Stephen Kesler, titled Out of the Blue, was eventually painted in rainbow colors by a separate artist and attracted a swarm of media attention and division among Salt Lake City residents.12 While the artists have not explicitly tied the sculpture to LGBTQ rights, the sculptor’s intent has been to celebrate the artistic and unique aspects of this eclectic neighborhood of the city. Critics of this whimsical public sculpture have emphasized its seemingly discordant subject matter relative to Utah’s desert and landlocked terrain. Such feedback highlights the reverence for representational art above all other forms of expression, a sentiment still prolific in more conservative states that view art for its own sake to be superfluous.

While monuments such as those to Brigham Young and the early pioneers enshrine a particular notion of Euro-American prosperity, episodes of resistance to this theocratic hegemony began even in the late-19th century and today, public art pays homage to persons of color often forgotten by predominant accounts of state history, Utah’s large LGBTQ population, and women trailblazers. In subtle and overt ways, these counternarratives present not simply a response to the popular view of Brigham Young’s place, but a more accurate and well-rounded view of history as that which evolves and expands over time rather than a continuation of events that stem from a singular religious origin. While Utah remains among the nation’s most conservative and religious states, the predominant culture is taking notice of such changes.13 And while Utah seemingly avoided the massive backlash and call for monument removal that affected various notable cities throughout the United States during 2020’s Black Lives Matter civil rights protests, changing demographics and political division may place renewed attention on lifting the voices of those outside this predominant narrative.

the Blue, 2022, Salt Lake City’s Ninth and Ninth neighborhood. Photo: Daniel Sowards, 2022.