What does it mean to be a dancer in a post-biological age? This question was posed by a student in one of Dawn Stoppiello’s classes in dance, new media, and technology at the University of Southern California. We’re not really post-biological (yet). Even when expressed by avatars in video games or virtual reality, the basis for the digital dancer is still a human one. Still, we are so immersed in technology that thinking about the future of this inherently embodied art form can feel dissonant.

On the other hand, the relationship between dance and technology seems natural. Science and art share the creative foundations of curiosity, experimentation, and serendipity. “They’re totally harmonious,” says Oliver Tobin, Director of Martha Graham Resources, the division of the Martha Graham Dance Company that oversees archives and licensing. “With dance and technology—for performance, preservation, and creation—it’s all possible.” How, then, is technology influencing and becoming a part of those facets of dance?

Making the performance of dance accessible to broader audiences is an important consequence of the union. “The wide availability of all types of dance on the internet has opened the eyes of dancers and choreographers around the world and brought us closer together as a dance community,” says Randy Barron, board president for MoveWest and an arts-integration instructor with Kennedy Center Arts in Washington, D.C.

As traditional concert-hall audiences age, it has become crucial for dancers and dance companies to share their art form—and prove their relevance—to younger viewers, which they have done in various exciting ways. World-renowned companies are able to share live performances on movie-theater screens in high definition. Meanwhile, online video challenges on platforms like TikTok and Fortnite bring dance into the social lives and parlance of teens across the world. Dancers are also incorporating digital media into their performance identities.

“The ultimate objective is to get dance out for people to see,” says Erik Sampson of New Mexico Dance Project. “As an auxiliary benefit, recordings allow us to share our creative process via social media platforms, which continue to build intrigue and connection with our audience base.”

“Many audiences have come to see dance as a fundamental way of communicating that crosses borders and languages,” Barron explained. “It’s an exciting time in dance history.”

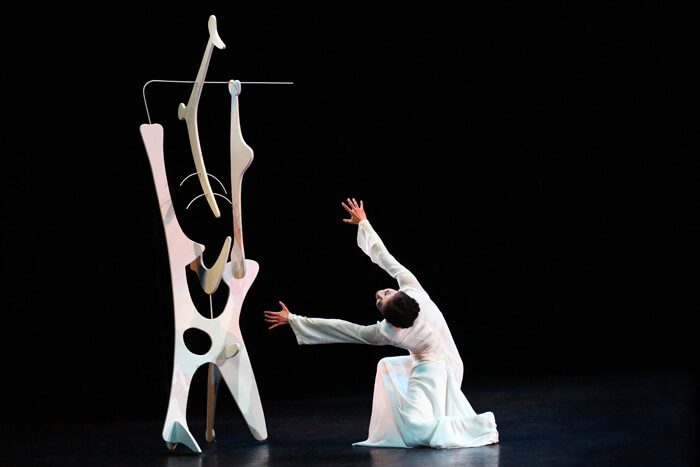

That it is, although the marriage of dance and technology is certainly not new. “We have film reels of Martha Graham dating back to the 1920s,” says Tobin. “And Graham was immersed in what was new technology at her time. She was a pioneer in costume, set, and lighting construction.” Indeed, her collaborations with sculptor Isamu Noguchi resulted in primal landscapes for the stage, pared down and exuding mythic power.

The wide availability of all types of dance on the internet has opened the eyes of dancers and choreographers around the world and brought us closer together as a dance community.

Artists have been seeking the message in various media for decades (centuries, really). What has changed across time is the media. “I’ve been working with ‘new media’ for thirty years, so why is it still called ‘new’?” asks Stoppiello, assistant professor of practice at the cutting-edge USC Glorya Kaufman School of Dance. After years asking this question of herself and students, she has devised a two-fold answer:

For one, I think “new media” refers to our ever-increasing ability to manipulate space and time. It doesn’t refer to a specific piece of gear, whatever the newest thing is, but what that gear does, which is allow us to accomplish that manipulation.

The other part of “new” in “new media” is you. And here I point to the students. They have their own sensibilities. Their relationship to society as it is now is going to infuse whatever tools they’re using with that perspective.

Mimi Yin, assistant arts professor at NYU Tisch’s Interactive Telecommunications Program, says her work begins with another instructive question: where is the intersection between choreography and computer programming? Space emerges as an answer here, too.

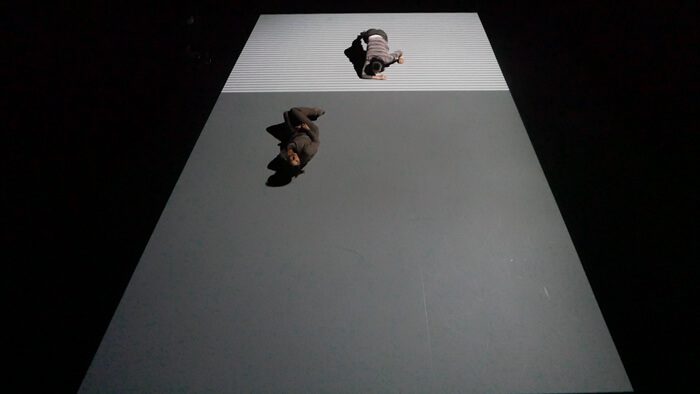

Yin’s work coordinates light projection with choreography in real time. Infrared light is bounced off of dancers to collect depth data. An algorithm processes this data to determine the position and orientation of the dancers. Floor projection lights then change, depending on the dancers’ movements. The space is bisected, one dancer in dark and the other in light. The shadows and shapes in the space change as the dancers respond to each other and the light intervention, which in turn continues to respond to them.

“It looks a little like minimalist art,” Yin explains. Yet the relationship of the lights to the dancers is quite complex. “When we watch dancers, we’re aware of their bodies, because we’re used to seeing what’s there,” she said. “We’re not used to thinking about how they divide up negative space.”

That negative space is integral to the perception of dance. The lines of the body are defined by contrast to the space through which they move. Yin’s use of light makes space a more conscious aspect of that. “You become aware of the space they inhabit, and it starts to feel more like architecture,” she says. Such technology can be used as an ingredient in the creation of dance as well. Yin is translating her program into an easy-to-use graphic user interface. The idea is to make the technology available to all as part of their own choreographic process.

“Whatever that media output is, it should be an integral part of driving and defining the choreography, not just another layer on top,” says Yin. “It should have a relationship to the dance that we associate with music. That may be an impossibly high bar, but I think that’s the goal.”

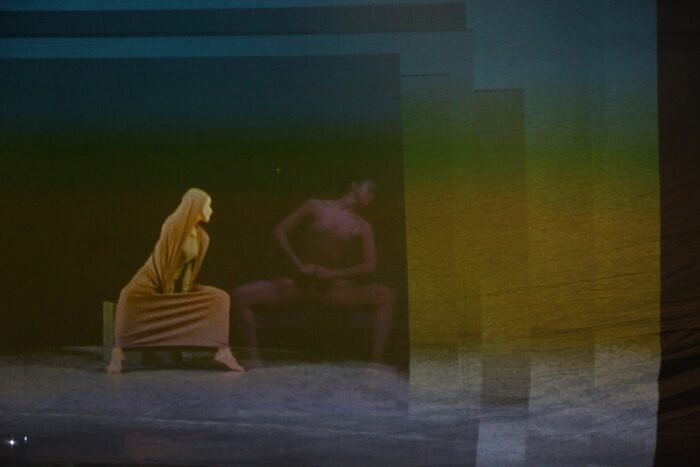

BodyVox, a company celebrated for its integration of dance, theater, and media, provides fascinating examples of this. Jamey Hampton, co-artistic director, says that technology should be in service to the story or concept that the dance expresses. For example, BodyVox’s The Cutting Room is a playful tribute to a collective nostalgia for old Hollywood and classic film. The dancers engage in a cloak and dagger chase through changing set designs and projected scenery from both real and “reel” locations. Other pieces are far more abstract. “We’re creating this puzzle that just keeps unfolding for the audience to play with,” says Hampton. “If they know where we’re going before we get there, why would they come?”

Technology is also aptly applied to the transmission and preservation of dance. As with performance, this area of the dance world is very much not post-biological. But media are being used in innovative ways that breathe new life into dance history.

The Martha Graham Dance Company has an extensive archive, which Tobin oversees. Relevant materials from the archive, including interviews, video, photographs, and notation, are compiled into “digital toolkits” used for reconstructions. “If a ballet company or a university is going to do a Graham ballet, they receive this packet of materials dating back to the earliest incarnation of that dance, all the way up through the generations to the present day,” says Tobin.

“The personal element is key,” he emphasizes. Despite the company’s trove of reference materials, Graham’s legacy is still transmitted primarily in person. “If there is no one who had contact with the work, an alum of the company or school, we send a regisseur to work with them, with the understanding that that person will pass the baton to someone at the institution. But the toolkit allows the school or company to get started and continue the rehearsal process without a Graham representative,” says Tobin.

“Dance is this storytelling from generation to generation, person to person. That’s always in the air, that sense that you are passing down this personal memory,”

This is typical and reflective of a long tradition of ballet masters and mistresses, rehearsal directors, and répétiteurs. These are usually dancers who had close, personal experience with a choreographer and their oeuvre. These artists become living vessels and transmitters of the work. “They are invaluable in every type of way,” says Kate Lydon, former American Ballet Theatre ballerina and artistic director of their studio company. She is now the director of dance at Saint Paul’s School in New Hampshire. “They connect you to generations.”

That connection is crucial. “It’s a relationship built on trust, a responsibility to try to understand, an empathy,” says Fiona Lummis, a master teacher and stager of the works of Jiří Kylián. She performed with Kylián’s company, Nederlands Dans Theater, for two decades and is described as one of the choreographer’s muses. Many iconic Kylián pieces and roles were created for her during her performing career.

“You have the whole background of how a work was built,” says Lummis of her role as a stager. “You bring everything with you—what was the piece that he made just before, what led into this or was in total contrast to that. There is a rich language and landscape around any given piece, so much more than ‘this step is on count six’ or ‘you angle your wrist like this.’” For example, she continues, “I’m about to work on Whereabouts Unknown. In this piece, Jiří gave us the image that it was as if we were dancing on sand, like we were tracing our footsteps. He always worked with such rich imagery and vivid visual ideas.” Kylián, who is alive but no longer actively working with Nederlands Dans Theater, has a website where he provides context for his creations through various media. Inevitably, for the luminary choreographers of the twentieth century, there will come a time when artists’ only point of contact is such digital collections.

“Dance is this storytelling from generation to generation, person to person. That’s always in the air, that sense that you are passing down this personal memory,” says Lummis. In a fascinating way, the legacy of a choreographer becomes a living thing as it is transmitted through generations of dancers who go on to remember and restage the work. The stewardship Lummis mentions takes an active, creative role through interpretation and the subjectivity of memory.

Digitally preserved historical reference material aids répétiteurs in their mission to preserve and pass on a legacy. But dance archives are not fossils. “We want to use the archive as a living library,” says Tobin. Technology is helping to revive dance history as an active part of new creative processes.

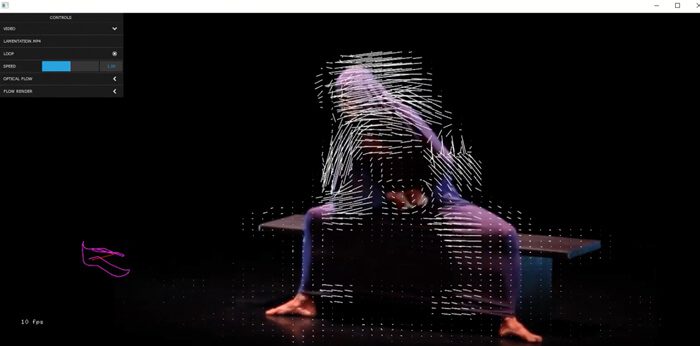

To this end, the Martha Graham Dance Company participated in a Google residency last year. In one especially moving experiment, computers were connected via cameras and sensors to a dancer performing Lamentation, a solo expressing grief. A camera photographed the dancer to create a real-time trail of images following the movements. The computers also learned to pair each moment of the dance with an image of Graham dancing the same part of the solo from the archives. These images were cast on a scrim, appearing to perform with the soloist to a ghostly, time-blurring effect.

This experiment was so successful that it was integrated into a performance in North Carolina in September. “We wanted to experiment and generate questions,” says Tobin, “but we were also hoping that the idea would make its way outside Google’s walls to the theater. And that’s what’s actually happening now.”

Where is this all heading? “Where I hear the most energy is around immersive environments and user-experience design,” says Stoppiello. “But at the same time, there’s also pushback against the digital curation of our lives, a resurgent interest in physicality and the embodied.” This gives dancers a new creative opportunity moving forward, she hopes. “I want my students to understand that their embodied knowledge and way of consciously moving in space, as dancers, is special. My goal is to give them vocabulary and tools so they can be part of the creative force that invents whatever comes next.”