Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver

September 21, 2018 – January 27, 2019

I went to Denver and had an out-of-body experience. Walking into the MCA Denver, a David Adjaye–designed museum, I was immediately met with the presence of a radiant, sun-gold screen that I soon understood to be a mosaic of rolled mirrored mylar embedded between two galleries. Untitled dissolves the contours of a body standing across from the viewer in the other room as the mosaic patterning carves into the passerby’s form. For reference, imagine standing in front of a steamy mirror to see a blurry version of yourself staring back. Only here, the installation bonds two separate rooms in a way that feels like a respirator circulating light and air through spaces. Even without bodies in space, the installation is constantly activated by natural light.

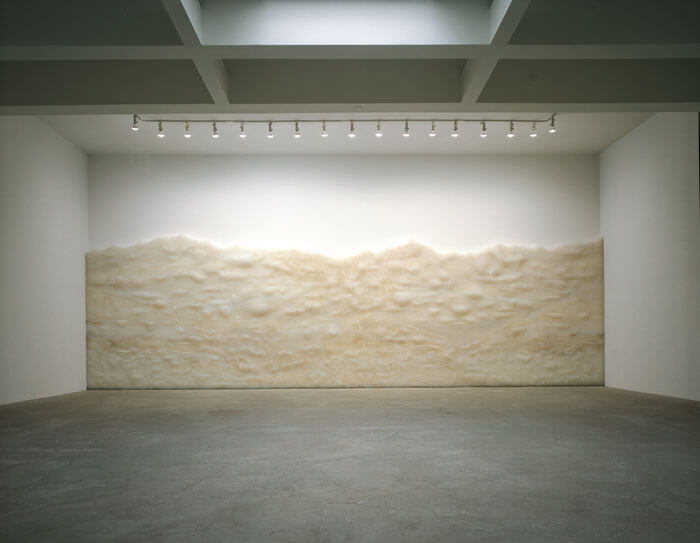

Facing this small work is Haze, a wall-to-wall installation of thousands of plastic straws cut to various lengths that call to mind everything from topographical maps to blistered skin.

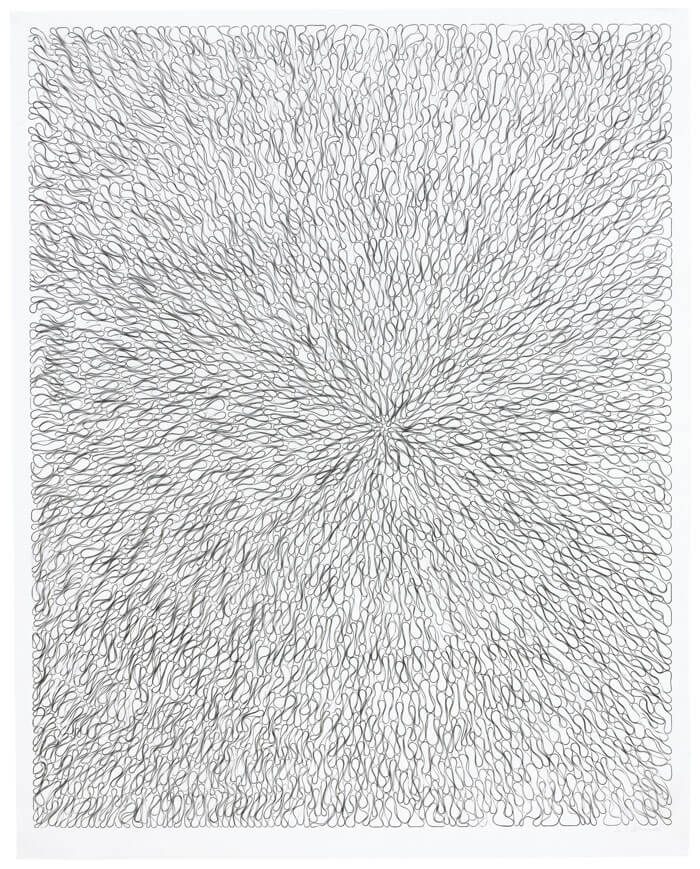

The gallery to the immediate right of Untitled displays two works, Haze and an early sculpture on a plinth that, at first glance, I thought was Eva Hesse. The show frequently calls out the styles of Hesse and Sol LeWitt by echoing industrial materials through process and repetition. A small cement pad, Untitled (1991), is an antiform and lies like a pillow. Looking at this early work, it’s remarkable to consider how clearly defined Donovan’s interests have been, from the start of her career to now, through her consistent use of repetition and multiplicity to elevate common objects. Facing this small work is Haze, a wall-to-wall installation of thousands of plastic straws cut to various lengths that call to mind everything from topographical maps to blistered skin. Look up Rosalind Krauss’s Sculpture in the Expanded Field and you’ll find a picture of Haze. While many viewers stand mouths agape at the idea of clipping and adhering hundreds of thousands of straws, I’m indifferent to labor and duration. The work takes time: so what? Instead, I lose my mind over the honeycombed waves with optical clusters of tan and ochre that emerge from what I understand to be uniformly opaque white straws. The texture and translucency of the combined straws create a visible soft surface with the density of soapstone.

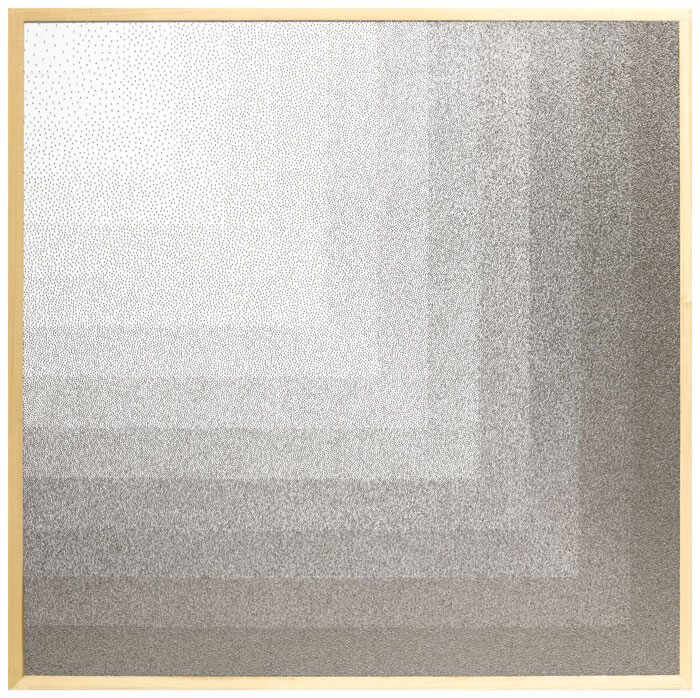

Donovan’s floor sculpture, Untitled (Plastic Tubes), speaks to LeWitt’s Variations of Incomplete Open Cubes—also a floor piece of painted wood cubes missing sections—through geometry, process, and material and then pushes the needle even further. Untitled is a grid of sixteen variations on a cube comprised of clear plastic tubes on a Corian base. There’s an impossibly clean transition from white to cool gray where the density of clear plastic tubes is greatest. It’s like materializing a motion blur, lifting it off a screen and pulling it into three dimensions. One cube alone takes my mind a minute to process, but the grid forms a field of objects that kept short-circuiting my vision and internal problem solving. I leave considering Donovan’s choice of materials, including plastic straws, mylar, tar sheeting, Slinkys, and plastic tubes. Because manipulating light is her priority, her options among everyday objects narrow down quickly to modern materials, thanks to technological achievements from the ’70s forward. This material progress is a defining way Donovan carries the post-minimal baton forward. The materials reference science and technology, and with this, the sculpture is embedded with the pathos of modern life. What a world.