Michael Gadlin, an artist and the executive director of PlatteForum in Denver, talks about the influence relationships and community have had on his creative practice.

“I couldn’t have gotten to where I am without all my connections,” Denver-based artist Michael Gadlin says while sitting in his studio and reflecting on the inspiration, encouragement, and support he’s received from others throughout his professional art career.

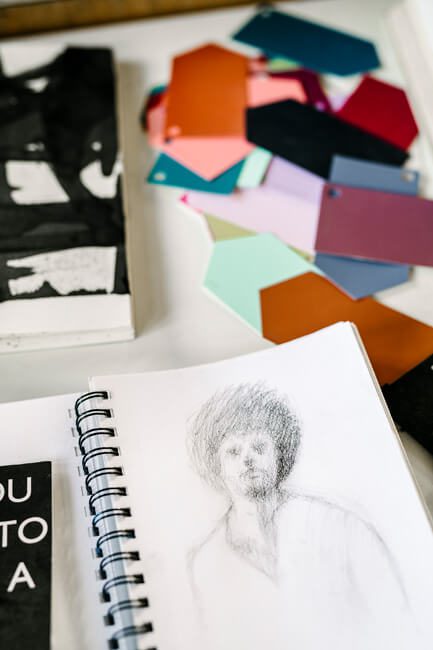

Located in an industrial area of the Globeville neighborhood, his ample, high-ceilinged workspace is filled with art books, completed paintings, works-in-progress, and various ephemera he has collected over the years. The room boasts wall-to-wall, south-facing windows that offer ideal, natural lighting for illuminating the space.

Two in-process, unstretched paintings adorn the western wall. The artworks—which also contain paper elements collaged into their surfaces—are portraits that employ abstraction in order to “disrupt the figure.” Always one to pay homage to those who preceded him and to highlight his aesthetic inspirations, Gadlin notes, “I was really influenced by Francis Bacon early on [and] seeing Picasso’s collage” work. Just as these past masters found idiosyncratic ways to abstract the human form, Gadlin explores his own visual idiom that traffics in the tensions between representation and abstraction. He also names African art, de Kooning, Motherwell, and Pollock as historical touchstones that have guided him throughout his artistic development.

The connections Gadlin fostered over the years are not just historical; they are, in fact, deeply personal. “My mother was a writer. And my dad was a junker—very industrial, very blue-collar. [She] exposed me to art and museums, and [he] exposed me to scrap metal and how to pull apart an engine. There is this natural ability for me to meld those two worlds together.”

Of the CNC-fabricated, modular sculptures he designed for Shades of Significance—his 2019 solo show at K Contemporary—Gadlin notes, “It dawned on me as I was making these elements—as they fell from the wall, and we set them up so they were kind of everywhere—how much it reminded me of [my father collecting] scrap.”

“What started out as an aesthetic need to do something different,” he explains, was actually “drawing on the familiarity” of his personal life. The installation, which at first seemed to him “chaos and elements in piles,” transformed into an homage to his “dad’s truck stacked and tied down with junk.” But more than just fusing fine art with junking, Gadlin believes his upbringing allows him to connect cultural divides. “Being bi-cultural and bi-racial, I have consciously thought of my work… as being a bridge that brings [disparate] worlds together. It is an amalgamation, if you will, of these opposing experiences.” To this extent, he says, “My figures are disjointed and culturally ambiguous on purpose. Because that’s how I grew up, felt, and navigated the world.”

As a young artist, integrating into Denver’s art scene was another exercise in cultivating connections. Gadlin reminisces about the mid ’90s when he returned to Colorado from New York City after earning his undergraduate degree in fine arts from Pratt. He developed relationships with established Denver artists such as Roland Bernier, Quang Ho, Jeff Wenzel, Emilio Lobato, and Phil Bender; likewise, he connected with gallerists and curators such as William Havu, Sandy Carson, Mary Mackey, and (more recently) Doug Kacena of K Contemporary.

We bring in artists, and I get a chance to learn about them, talk about their involvement and influence in our community, and create programs with them. [It helps me] never to forget what’s going on. What’s new? What’s fresh? —Michael Gadlin

“I needed to dig my heels in and find out what [the art world] was about. How I could survive. If I could survive,” he says. After nearly thirty years of practicing art, he credits his survival to “a lot of great mentors and involving myself ” in various local communities.

It’s no surprise, then, that Gadlin gives back to the community just as much as he’s received support from it. For years, he taught at the Art Students League of Denver and in the Denver Public Schools.

“I work with young artists whom I now mentor,” he says. Although the city has become financially untenable for most young artists, Gadlin strives to “maintain pockets of artistic and creative opportunity and diversity so that [Denver] doesn’t completely [disappear] into the landscape of winter sports, cannabis, breweries, restaurants, and tech.”

His new role as executive director of the art non-profit PlatteForum is his most recent effort to support younger artists. The organization “is a safe place to express, a caring place to give and meet needs, a place for resources, a place for discovery—both self and beyond—and also a place to contribute,” he says. “These kids usually don’t have opportunities or communities they can relate to or lean on,” so PlatteForum provides them with a support system helmed by “different kinds of leaders and makers.”