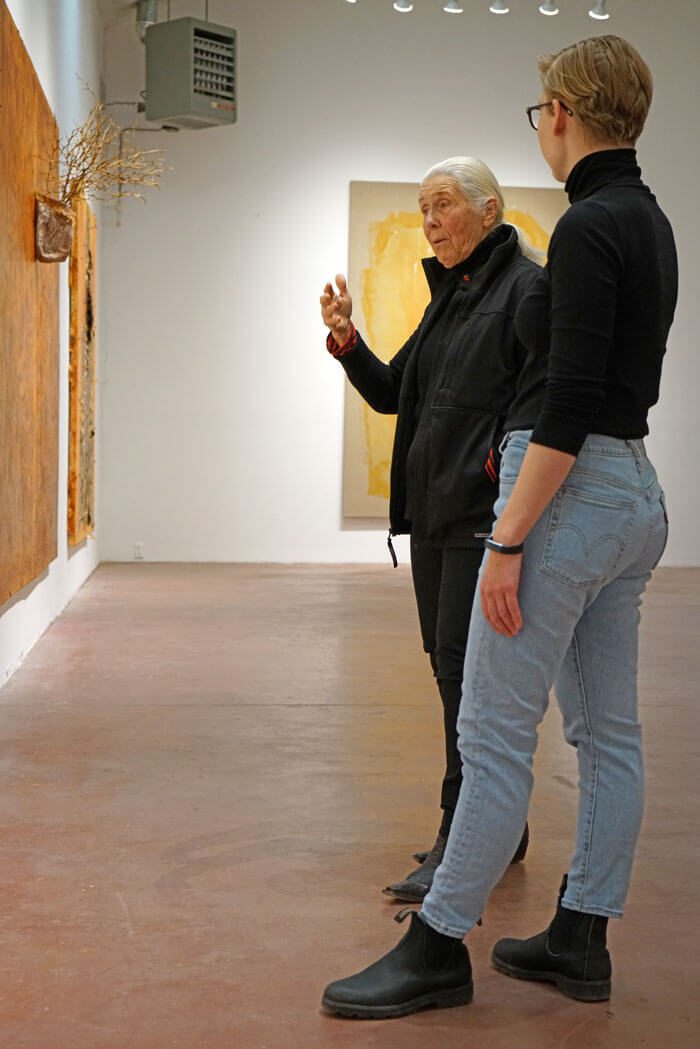

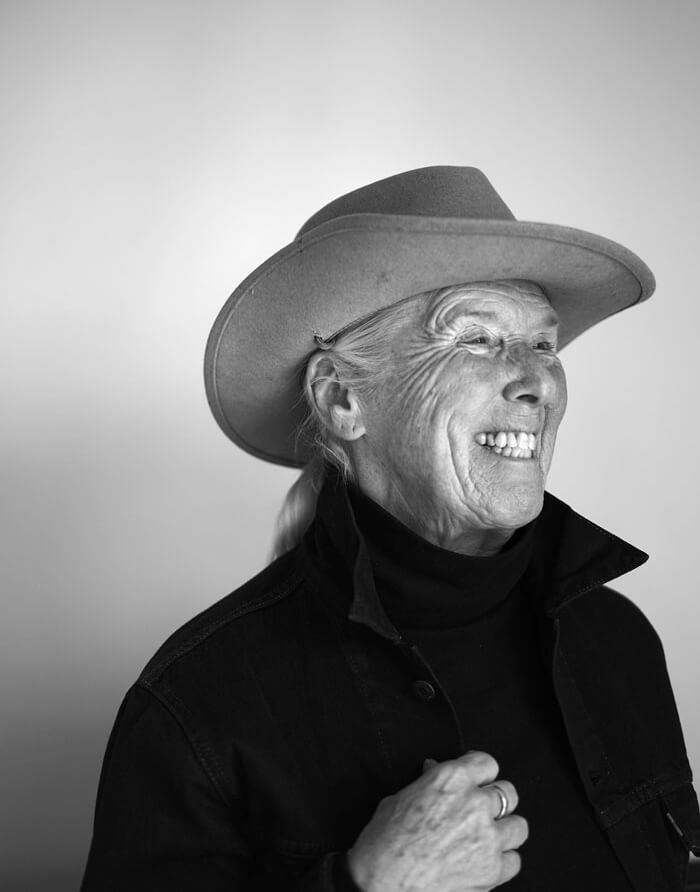

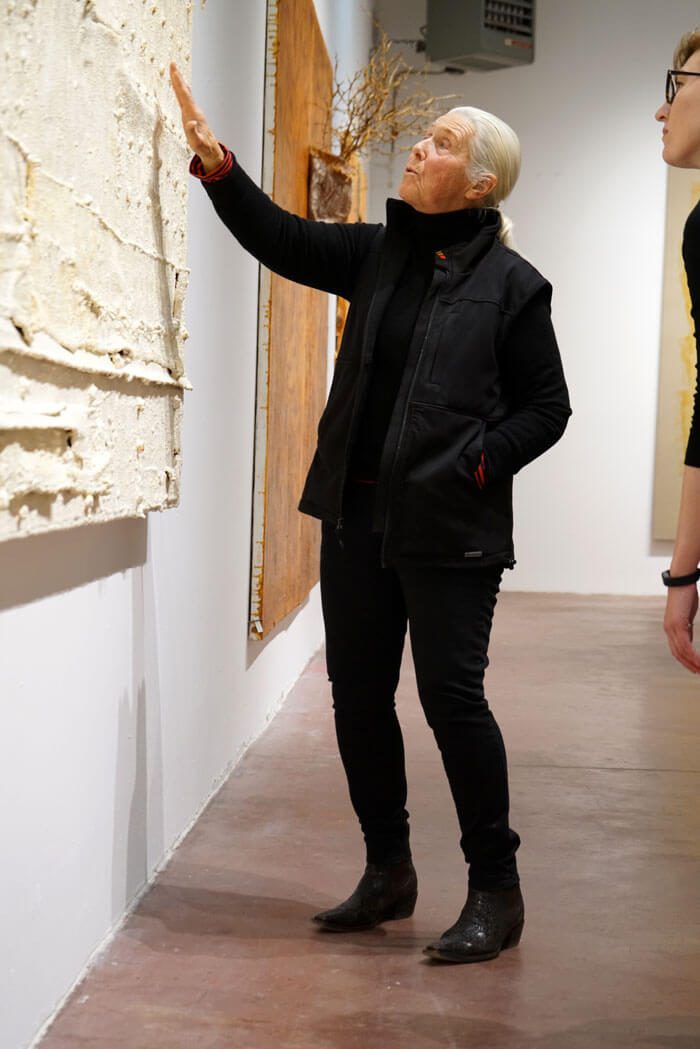

Harmony Hammond is lying on the floor beneath one of her paintings, craning her neck within inches of the canvas. “I’m doing edges,” she tells me. I first heard of Hammond when I came across the catalogue for Out West, a 1999 show she curated at Plan B Evolving Arts in Santa Fe that brought together 41 lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and two-spirit artists from the Southwest.

I was living in Texas at the time, but soon enough I had moved to Santa Fe and was working for Hammond as an ersatz archivist, cataloguing and tracking her works in a database from the office connected to her massive Galisteo studio. I did my best not to interrupt her while she was in the studio, wincing as I heard the bangs, booms, and scrapings from the next room—sounds of her highly physical painting process.

It was apparent to me immediately, and became even more so over the time I worked for her, that Hammond’s life and work are utterly continuous with one another. For several months, her series Presences, over six-foot high sculptures made of acrylic, dye, cloth, rope, metal, and wood, hung in her living room, some beneath sheets. She called them “the girls.” They were “hanging out,” and needed space to resume their full embodiments. Originally from Hometown, Illinois, a land of “duplexes, nothingness, and bland sameness,” in high school Hammond took the El to the Saturday School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the bowels of the museum, classes full of “beatniks, nude models, and rotten still lifes—I loved it. Very different than Hometown.” She studied dress design and fashion illustration, and after class could walk the museum for free and look at the collections. This was her first real encounter with the art world, and the beginning of a lifelong artistic practice that today encompasses her home, studio, and small orchard in Galisteo.

Clayton Porter and I visited Hammond in her studio on the eve of a major survey show of her work at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Material Witness, Five Decades of Art, which is on view from March 3 to September 15, 2019, in Ridgefield, CT. A solo exhibition of her work at White Cube in London opens September 5th. This year her work will also be included at a number of queer-themed exhibitions, which mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall riots. the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall riots. Hammond moved to New York just after Stonewall, where she co-founded two foundational second-wave feminist institutions: A.I.R. Gallery, the first women’s cooperative gallery in New York, and Heresies: A Feminist Publication of Art and Politics. An activist, curator, and teacher, Hammond went on to write Lesbian Art in America: A Contemporary History (2000), and is known for her use of materials that mingle content with abstraction.

Jenn Shapland: How do you choose your materials?

Harmony Hammond: I think materials and how they’re used, how they’re manipulated, is one way of bringing content into abstract work. I don’t have an idea and then go seek the materials. I respond to a material for its formal properties, for what the material is like physically, and then I begin to work with it, manipulate it to see what I can do with it. As I work with the material, I begin to think about what I’m getting. But in the beginning, I try to just be open. As I’m working with the materials, I begin to think about what’s going on here, and how does the history of that material—be it traditional or not—and what I’m doing with it, how does it suggest meaning in the artwork.

In these paintings from the 1990s, latex rubber calls up skin and body. It would be pretty hard to use this material without body associations. They were done at the time when the AIDS epidemic was devastating the New York art world. In this painting, Codes of Meaning, the body reference is further emphasized, because I’m bringing the hair of two people together in the latex which suggests body fluids: it’s both sensuous and dangerous, very charged. This is blonde hair; this is dark hair. For this painting called Endangered, I used a zebra skin that a friend gave me. I just could not put it on my floor, so I placed it, a real animal skin, in a field of latex rubber suggesting or simulating human skin.

Can I backtrack for one second and ask whose hair is in this piece?

I don’t remember.

Someone you knew?

Probably, yes. I used hair on and off for years, and when I first did it in the ’70s I got some hair from a hair salon—that was not my thing. I usually use hair of people I know; I ask for their hair. Or I use my own hair, or my daughter’s hair.

And where does the metal piece come from in this work, [Untitled, 1991]?

Oh, who knows? It’s from 1991. These latex pieces with 3-dimensional elements came out of the earlier Farm Ghosts series where I scavenged old rusty corrugated roofing tin and metal gutters from abandoned farms between here and Tucson, where I was teaching. I think of gutters as circulatory systems: they’re supposed to be moving life fluids like water, but in my paintings there are no life fluids. There may be a little dribble of flesh or blood, but no water. Usually I use materials as I find them. I don’t alter them much. I found the gutter this way, bent, pieced, and repaired. Somebody mended it. Also, I like ladders; I like tools, they all have histories; I like gutters; I like water troughs, things that have a purpose.

Useful things.

But people have also altered them. Or personalized them. Going back to materials, especially found, repurposed, or recycled materials, they always bring their history, their stories, their narratives into the work with them. And in this case, one could even say they bring in other bodies, other peoples. We don’t know who, but somebody repaired this gutter. Occasionally, I use natural materials. Hopefully, by juxtaposing materials such as hair, straw, metal, or fabric with materials such as latex rubber or paint, I initiate new feelings, thoughts, or conversations. That’s why I recycle materials. To bring content into the work.

Talk about New Mexico and how living here has changed your work.

Well, I’ve always worked with found materials. When I lived in New York, my work was made out of the rags that women friends gave me—thereby literally putting my life in my work—or fabric I found on the streets. My daughter and I would pick rags. We would go to the garment district and collect the end cuts of bolts of knit fabrics that were discarded in dumpsters or left at the curb in big plastic bags. Here, it’s different. There’s not much thrown out in Santa Fe. But I do find different things in different places, both urban and rural. And these things reflect place. Not landscape but place, which I define as a peopled space. It either is peopled now or it was peopled in the past, but now there’s no one there, like on those abandoned family farms—where is everybody? What happened to them? So it is the materials from the farmsteads, fabric from the garment district, or an old quilt left by a friend, that engage narratives of place.

I think I’m here because I like the big, open space. I can’t say that it changed my work, but the very fabrics and textures around me have changed and those have found their way into my work. Rusted roofing tin and straw pieces used in adobe are examples. I paint with oil on canvas (of course canvas is a material, too, as is paint—and they each have their histories). We were talking about martial arts before the interview. In some of my work, I’m using canvas that used to be an Aikido mat cover. Aikido, a Japanese martial art that I studied for thirty-six years, is practiced on woven straw mats called tatami that are covered with canvas. When those mat covers wear out, they have to be replaced. I was given the old canvas covers, which I used in place of traditional painting canvas, thereby calling up the bodies that had traversed that canvas for years, including my own.

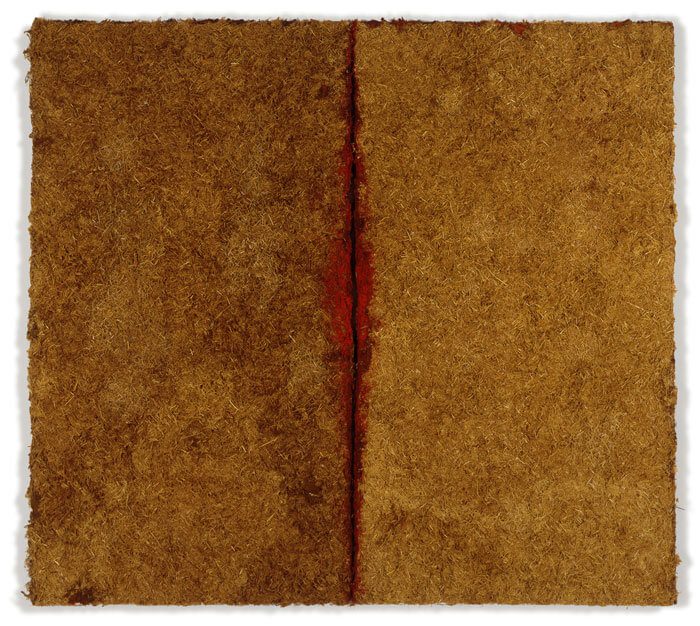

In the most recent paintings, I’m using burlap from recycled coffee sacks, which I get here in town. I cut them up, and collage them onto canvas in order to build a textured surface. In the Chenille paintings, like the one hanging over there, the texture and warm white color suggest the comfy softness of tufted chenille bedspreads, but with an edge as under layers of color push up through splits and tears in the burlap, ooze out of grommet holes, or seep into the white paint making it a little brownish gold. It’s a question of what is hidden, what’s buried underneath and how does it assert itself? I try to give agency to what’s hidden or buried underneath the comfy white cover.

It’s intentional that the seams show, that we see things are pieced together. I don’t like digital seamlessness. Piecing, patching, fraying, layering, suturing are loaded with meaning.

When I say something’s bleeding through and asserting itself through the whiteness, I mean that metaphorically and not just formally. That’s how I work. The physical functions metaphorically to provide content. That’s why all the seams: the frayed edges are important to me. It’s intentional that the seams show, that we see things are pieced together. I don’t like digital seamlessness. Piecing, patching, fraying, layering, suturing are loaded with meaning.

Do you feel a part of a legacy of artists, specifically women artists, working in New Mexico? What about a legacy of queer artists or lesbian artists? Or a queer or lesbian community?

There’s a long tradition of artists coming to New Mexico. I’m one of those artists, and I’m one who didn’t just come and go but who came and stayed. I see myself in multiple artistic traditions such as abstract painting, expanded painting, feminist art, or queer art, just like I think any artwork participates in multiple narratives. The art and artist can be addressed within any of those narratives. In terms of New Mexico, I am very aware of being part of a tradition of women artists, photographers, anthropologists, and writers, many of whom identified as lesbian or bisexual, who came West because of the wide, open space. It’s outlaw territory. You’re free to be who you think you are or want to be. For women who couldn’t fit in where they grew up on the East Coast, or who didn’t want to be what the social mores of the time expected of a young woman, what she should be, or who just wanted to do something else, but didn’t have money to go and carve white marble in Italy; they went west. I love that that legacy as well as the history of strong creative women who have always lived here.

What made you choose Galisteo?

Once I had made the decision to permanently settle in New Mexico, I walked around all the places that I liked, and it just had to feel right. I looked at empty land; I looked at existing structures. I liked old buildings, but a lot of them were fixed up and expensive. You paid a lot of money for someone else’s taste, which I usually hated. I would walk the land in different weather, different times of day. I liked many villages up north, but I realized that I wasn’t really welcome there. This was in the eighties. As much as I wanted to think that people would see me working on the property—working does count for a lot—and I would fit in and be accepted, I slowly realized that I shouldn’t be living there. Here, in Galisteo, it felt very good. The land felt good. The mix of people felt good. I had seen this old stone structure, the lanera or wool barn, from the highway, but I had never walked back here to check it out, because it was on somebody’s property. For the most part it had not been lived in, so it was pretty rough going at first. Many people rolled their eyes when I bought it. Everyone except Lucy [Lippard]. Like me, she had lived in raw industrial lofts in New York, so could imagine how the rough interior space might be fixed up for living.

As an artist, do you feel like you have to be selfish, to protect your time or insulate yourself from the world?

Selfish isn’t the word that I would use. Of course I protect my time. I’m very structured about my time, or I wouldn’t get anything done. I learned to do that early on as a single mom. Because I was the only one in my group of women artist friends in New York who had a child, I used time very differently than they did. As a single parent, I learned to use little bits of time productively. You can’t wait to have long uninterrupted stretches to work on your art, because that time never comes. I could do certain kinds of work when my daughter Tanya was around, but for other stuff, I had to wait until she went to bed. Then I could focus. I also chose to have a half-time job (and half a salary) in order to have regular time in the studio.

I don’t separate what I’m doing outside and what I’m doing inside, or what I do in the house from what I do in the studio. For me, they just kind of flow together and feed each other.

I remember being here working at the computer and seeing you outside dragging a huge piece of metal across the yard. You are so active. And your work really involves your body. It’s really physical. Can you talk about that a little? About how you use your body in your work?

I am very physical. Manipulating materials is what I do. It’s obviously very important to me and I get pleasure from it. Oh, I know what I was going to say about your word, “selfishness.” I think what I’m more aware of in relation to time (other than there is never enough of it), is “privilege.” I have an awareness of privilege. To be able to work, even as a single mom, or when I was commuting and teaching, to somehow be able to do my work, to be able to do what my passion is, and be recognized for it, is a real privilege. Yes, I have to set boundaries; yes, I have priorities, and the work is the major part of my life, for sure, but other things, like teaching or the martial arts that I did for so many years, they’re part of the work too. I don’t separate what I’m doing outside and what I’m doing inside, or what I do in the house from what I do in the studio. For me, they just kind of flow together and feed each other. And normally it feels pretty good, unless I get too anxious about something. The multitasking can get out of hand.

And so you feel like your garden space, your house, is all continuous with your practice?

It’s all “the work.”