Spirit of the Land is a love letter to the Southern Nevada desert: a series of exhibitions opening in late March across three venues celebrates the East Mojave landscape.

Land acknowledgment for Spirit of the Land:

“This mountain and the lands surrounding it are considered sacred to at least twelve different local tribes, including the Mojave, Hualapai, Yavapai, Havasupai, Quechan, Maricopa, Pai Pai, Halchidhoma, Cocopah and Kumeyaay, Nuwuvi (Southern Paiute) and Hopi. For the ten Yuman-speaking tribes, Spirit Mountain is considered their origin place.”1

•

“It’s the artist’s job to teach us to see.”2

—Lucy R. Lippard

•

The ability artists have—to make the unknown visible—is realized this spring in the Spirit of the Land exhibition series, a wide-ranging celebration of the East Mojave landscape of Southern Nevada. The main exhibition at the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art in Las Vegas, combined with two satellite venues in Searchlight and Laughlin, is intended to raise awareness about public land issues around these small communities located south of Las Vegas while highlighting the ecological importance, community ideals, and cultural assets of place.

Led by three curators—Kim Garrison Means, Mikayla Whitmore, and Checko Salgado—and in collaboration with townspeople, tribal members, land administrators, and conservation organizations, the culmination of each exhibition could only be attained through individuals confident in the work of others for whom conservation of these lands is paramount.

Lippard’s statement resonates with the ideas driving Spirit of the Land on multiple levels. Means says, “Artists communicate place to people who sometimes can’t see the land for themselves. Multiple voices can provide facts, but when art is used to tell stories about a place, one is transported.” Means, Salgado, and Whitmore characterize the work they are generating with Spirit of the Land as a love letter to the desert. The hopefulness of their message—we can save this, we can share this—presents a community approach centered on gaining strength in numbers and utilizing the power of art.

Each exhibition venue engages the public with art as a call to activism, inviting communities to see, value, and protect their shared land. The celebration of Spirit Mountain—Avi Kwa Ame in the Mojave language—and surrounding landscapes is the exhibition’s main objective, including raising awareness of current efforts to designate this region as Nevada’s fourth national monument. The 380,000 acres that form the proposed Avi Kwa Ame National Monument are comprised of a biologically diverse ecosystem amidst several mountain ranges, Joshua tree forests, grasslands, and natural springs. Monument status would protect Native American ancestral lands and preserve the surrounding lands for residents in the small towns of Southern Nevada.

This objective extends into a web of important issues, including past and present land use, community engagement, industrial encroachment, Indigenous sovereignty, and eco-activism. Their questions are geographically specific, yet reflect many of today’s concerns. What resources are found in our public lands? How do we protect them for the future?

The Curators

The exhibition’s curators have ties to University of Nevada, Las Vegas’s art department, and deeper ties to the lands of Nevada. UNLV professor Wendy Kveck is a common link, who began visiting Means’s Mystery Ranch in Searchlight in 2019 with students and artists, helping create a network that moves effortlessly between Las Vegas’s art communities and the lands and artistic events taking place further afield. Each curator has experience working in social activism and relishes engaging multiple individuals, groups, and institutions in their efforts. Their collective expertise supports efforts to share their profound experiences, while their nonhierarchical methods permit others to tell their own stories.

Each curator carries unique strengths. Checko Salgado is a known catalyst and conservationist in Nevada. He creates photo-based works and has curated land-themed exhibitions to help raise awareness regarding lands needing protection, including Basin and Range (2015), which toured statewide through Nevada Arts Council, and Home Means Nevada (2019), a photographic homage to the state’s federally protected lands, which was shown in Nevada and Washington D.C. He’s worked with conservation groups and politicians, including the late Senator Harry Reid, to successfully gain monument designations in Nevada: Basin and Range National Monument in 2015 and Gold Butte National Monument in 2016.

In early 2021, Salgado conceived of Spirit of the Land to support the work that his colleagues had been engaged in at Avi Kwa Ame, reaching out to Kim Garrison Means and the Searchlight Mystery Ranch to connect with local artists.

The ranch is a mystery in many ways: it doesn’t have an address; it’s not open to the public; the townspeople of Searchlight only recently learned of its existence. So, too, the town of Searchlight is an enigma; even the name of the town is a mystery. The aforementioned Senator Reid was born in Searchlight, his life and early struggles recounted in his autobiography.3 One chapter is devoted to unsuccessful attempts to uncover the origins of the town’s name. For Means, though, the most potent mystery is the way the land—its flora, fauna, seasons, and connections—unfolds and teaches the mysteries of life to those who will listen. It is only through time and observation that discoveries can be made in the landscape.

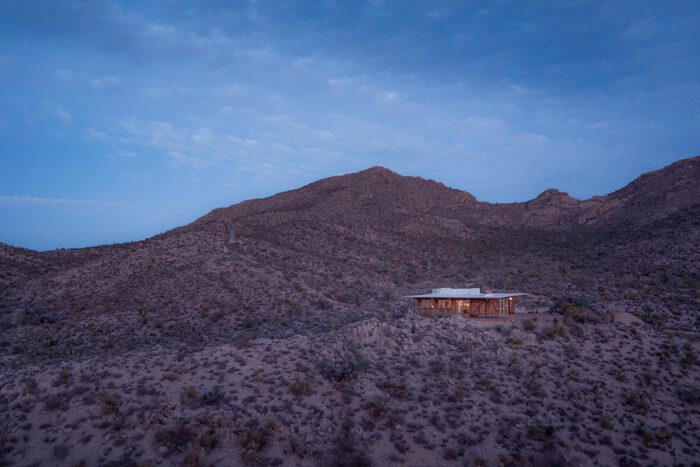

The Mystery Ranch was built in the early 1960s on sixty acres of mining claims by Means’s grandparents. Means inherited its stewardship in the early 2000s and began drawing inspiration from its desert ecosystem for her work with United Catalysts, a conceptual art collaboration established in 2001 with Steve Radosevich. Their creative approach to engaging systems and connections led Means and Radosevich, while MFA students at UNLV (where they were the first artistic team to apply to and graduate from a graduate program in the country), to invite artists and researchers to the ranch.

“People told us they had always thought the desert was a wasteland, but this desert was a paradise,” Means says, recalling some of the first visitors to the ranch who couldn’t believe the lushness of the environment. “Those reactions really moved us. We wanted to shift that mythology and give the desert a chance to speak to people directly, because when people are moved by connecting with nature, they feel more like protecting it.”

The third curator, Mikayla Whitmore, is an artist, writer, curator, and photojournalist whose identity as a nonbinary person working publicly across many spheres provides generative experiences. They speak with pride as a fourth-generation Nevadan with deep ties to the land. Their artistic and personal practice often refers back to the desert or landscapes on the outskirts of Las Vegas, where installations and images reflect both real and imagined worlds. Activism and community practice run throughout their efforts, including participation in the artist collective GULCH, comprised of six friends with long-time connections to the Las Vegas area.

The Community

Whitmore and their colleagues push back against the notion that the desert is a place where there is “nothing out there.” For them, it’s a heart mission to tell stories about the land. Whitmore and Means discussed the value of monument status in the Avi Kwa Ame area for Searchlight residents amidst conversations regarding overall regional changes. As Means states, “National monument designation would allow our local towns and tribal communities a seat at the table in developing an overall management plan for the area, and a structure for our continued input in the future, while maintaining all our current public uses of the public lands, including camping, hunting, and off-highway vehicle exploration on back roads, which Searchlight residents hold dear.”

Residents had previously not had a seat at the table but managed to fight off several ill-sited industrial projects, like wind turbines, with help from conservation groups.4 Means and her husband, Leland Means, have helped battle energy projects for fifteen years. When asked what more could be done to stop the encroachment of energy projects (that lend little positive impact to the fragile ecosystem or local community) the answer was to develop a regional national monument designation. The Mystery Ranch team helped spread the word in Searchlight to discuss issues, outing their own work to the community in the process. Their efforts helped the Searchlight Town Advisory board reach a unanimous decision to support the monument proposal. Means’s approach to working with the monument coalition team is in the same manner she works with Spirit of the Land: include every part of the web, from community to creatives to scientists, and listen to the stories.

A crucial part of that web is the curatorial collaboration with the Fort Mojave Indian Tribe, focused on visual stories from Indigenous voices. The Mojave are caretakers of Avi Kwa Ame for the twelve native tribes who hold this land sacred, with collaborations realized in part through ceremonies and pilgrimage. Monument status would assure the whole mountain is protected for Indigenous tribes. The eastern half of Avi Kwa Ame is protected, designated as Traditional Cultural Property on the National Register of Historic Places (1999) while the western half is claimed by all ten Yuman-speaking native tribes through their creation story. Acknowledging the vital role of Avi Kwa Ame by listening and working in tandem with the Fort Mojave Indian Tribe is ongoing and realized through community dialogue and inclusion in Spirit of the Land.

The Exhibition

By engaging Indigenous voices, community members, and professional artists, the diversity of the work provides entrée to the magic of these lands. Each curator worked with artists on their experience on the land, gauging process, continuing dialogue, and providing access to research, scientists, and historians.

More than forty artists, writers, and musicians created work in a variety of media for Spirit of the Land including painting, photography, sculpture, and video. To channel voices from the land, artists were required to spend time in the proposed monument area, often working collaboratively in their research with the curators and other artists.

One artist is Alan O’Neill, who spent his career with the Department of the Interior, at one time in the position of superintendent of Lake Mead National Recreation Area, situated on the eastern portion of Avi Kwa Ame. He is also a stained-glass artist, casting light with items found on and from the land. His Tiffany-style lamp incorporates mining-era bits of glass found at the Mystery Ranch along with quartz crystals and slabs of regional minerals.

Collaborative works are found across the exhibition’s three venues. Salgado has been working with local musicians who performed original music in the monument area. Their performances are presented as video, including footage from the region. Interspersed between Salgado’s videos is a series from United Catalysts: images of animals captured on the Mystery Ranch’s pond cam turned into video shorts as evidence of their existence. This is one example of the depth Spirit of the Land reaches: music and landscape can often be found together, while glimpses of animals that are rarely seen in person due to ongoing drought conditions add poignancy and a subtle call to action.

Artwork by community members from Searchlight, Cal-Nev-Ari, Nelson, Fort Mojave, Laughlin, and Las Vegas was encouraged so that their favorite aspects of the Avi Kwa Ame landscape could be reimaged as postcards. Workshops took place in Searchlight to help the community generate artwork for the exhibition, involving schoolchildren and seniors to create desert plant cyanotypes and animal block prints with materials funded by the local non-profit, Searchlight Betterment Organization. Workshops, performances, and panel discussions will continue during the exhibitions, with a public postcard-writing station housed at the Barrick, where visitors can write to their local and national representatives to share thoughts on Southern Nevada’s public lands.

After Spirit of the Land closes, the work continues, although it’s more accurate to call it a lifestyle or a calling. Collaborative and generative processes and projects are the way Means, Salgado, and Whitmore live and work. They embrace visual stories of beauty and import, where seeing a place means engagement in that place. The lens they—and we—see through is the lens of experience and the stories we tell and share. As artists, they expand the capacity for us to see.