Three San Antonio arts organizations leverage a land trust and other strategies to literally hold space on the rapidly growing city’s Westside.

A vibrant cluster of brightly painted one-story residential and commercial buildings, once three separate properties, occupies the northeast corner of Guadalupe and South Colorado Streets in San Antonio’s Westside. Outside the chain link fence that encircles the buildings, there’s a small raised-bed garden filled with native plants and a hand-painted aqua-blue Little Free Library. White text on the library door reads, “Take What You Need. Give What You Can,” a simple phrase that embodies the ethos of the Esperanza Peace and Justice Center.

At Rinconcito de Esperanza, the nonprofit’s headquarters, staff, volunteers, and community members mobilize. Under the shade of tall oak trees and large fabric shade sails stretched between rooftops, people tend to the garden and work on clearing land, which will soon be home to newly renovated casitas.

Inside the buildings, a handful of people share a meal in the kitchen, a pair meets to discuss community matters at a long dining room–style table, and women are in various stages of production in the MujerArtes ceramics studio. The interior is an explosion of creativity; its walls overflow with piñata-style sculptures, papel picado banners, garlands of artificial flowers, hand-crafted pottery and tiles, and curated spaces that speak to the neighborhood’s rich history of resilience.

Can [art] protect and uplift a community, instead of importing outsiders who only see the monetary value and potential of the land?

Rinconcito stands in stark contrast to the towering four-story apartment complex across the street, a neutral-toned monolith built in 2022. The Esperanza team and residents advocated for a building half the height that could house an equal number of units by dedicating less space to parking lots, which now sit mostly empty. Graciela Sánchez, who has served as executive director of Esperanza for thirty-six years, remarks, “Everything they promised, they didn’t do.”

Witnessing the uprooting of families and bulldozing of homes galvanized the community-focused, social justice–oriented organization to work strategically to ensure that neighborhood residents’ voices are heard in the ongoing development of the Westside. With the area facing economic struggles and San Antonio ranking as the U.S. city with the largest population growth in 2023, gentrification seems inevitable. A 2021 report from the University of Texas at Austin’s School of Law found that in five years “the City issued close to 1,000 orders to vacate and orders to demolish single-family homes,” more than half of which were occupied.

Gentrification often follows when artists and arts organizations enter lower-income neighborhoods. Affordable rent attracts creatives and, in turn, their artistic interventions generate new interest in the area, ultimately displacing long-time residents.

But can art be a force against gentrification? Can it protect and uplift a community, instead of importing outsiders who only see the monetary value and potential of the land, rather than the already-thriving culture? Longstanding arts and cultural organizations founded by San Antonio Westsiders, like Esperanza, the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, and San Anto Cultural Arts, are working to do just that.

The most radical approach is being led by Esperanza, an organization founded by Chicana activists and artists such as Sánchez, Susan Guerra, Carol Rodríguez, Gloria Ramírez, and Romelia Escamilla. Though its typical methods of engagement center visual, performing, and literary arts as modes of community building, information sharing, and rallying around social justice issues, more recently, Esperanza has established a sister organization, the Esperanza Community Land Trust.

What is a land trust? The answer is complicated because the terms of any particular land trust will be customized to the needs of those involved. Broadly speaking, a land trust is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization created to protect land, by taking ownership or stewardship of property. In the U.S., where owning property is a cornerstone of “the American Dream,” the framework of a land trust reconsiders longstanding societal ideas about land, ownership, and success by centering community and care over the individual and acquisition.

I said to the board, we either shut the doors or we buy a building, because we will continue to be kicked out.

Sánchez explains that while some speculate that residents may be hesitant to join the trust because they consider the land as an inheritance for their children, the real inheritance would be future generations’ ability to stay in the neighborhood. As a young organization, the board is still working out details of its procedures, but ultimately ECLT aims to own the land while the residents own or rent the homes, keeping properties in the trust affordable in perpetuity.

Esperanza’s founders learned early on the importance of securing property. In 1993, the organization was evicted from its original location following its fifth annual LGBTQ+ art exhibition. Esperanza was renting the space from oblate priests, and the eviction coincided with a leadership shift in the leasing entity, in which a more conservative-minded priest took the helm. Sánchez recalls, “I said to the board, we either shut the doors or we buy a building, because we will continue to be kicked out.”

With support from the community, Esperanza purchased its main office and performance space at 922 San Pedro Avenue, north of downtown. In just six years, they paid off a $200,000 loan, which Sánchez insists could not have happened without the support of residents. “One of my best memories is this viejita catching the bus, which would stop right in front of the Esperanza. She came in with her little handkerchief that was all folded up. Then she opened it and gave us five dollars.”

Those small donations added up, resulting in an organization equally invested in the community that invested in it. That investment is what makes it possible for the arts organizations that comprise the Westside Cultural Arts District, known as El Mero Weso, to be a force against gentrification—they are firmly rooted in the community they serve.

Similar to Esperanza, the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center was established as a direct result of the efforts of artist-activists. A group called the Performance Artists Nucleus—formed in 1979 by Darío Aguilar, Rodolfo Garcia, David Gonzalez, Angela de Hoyos, Juan Tejeda, and others—advocated for municipal funds to preserve Chicano, Latino, and Native American cultural traditions. Ultimately, they secured city support to renovate the historic Teatro Guadalupe.

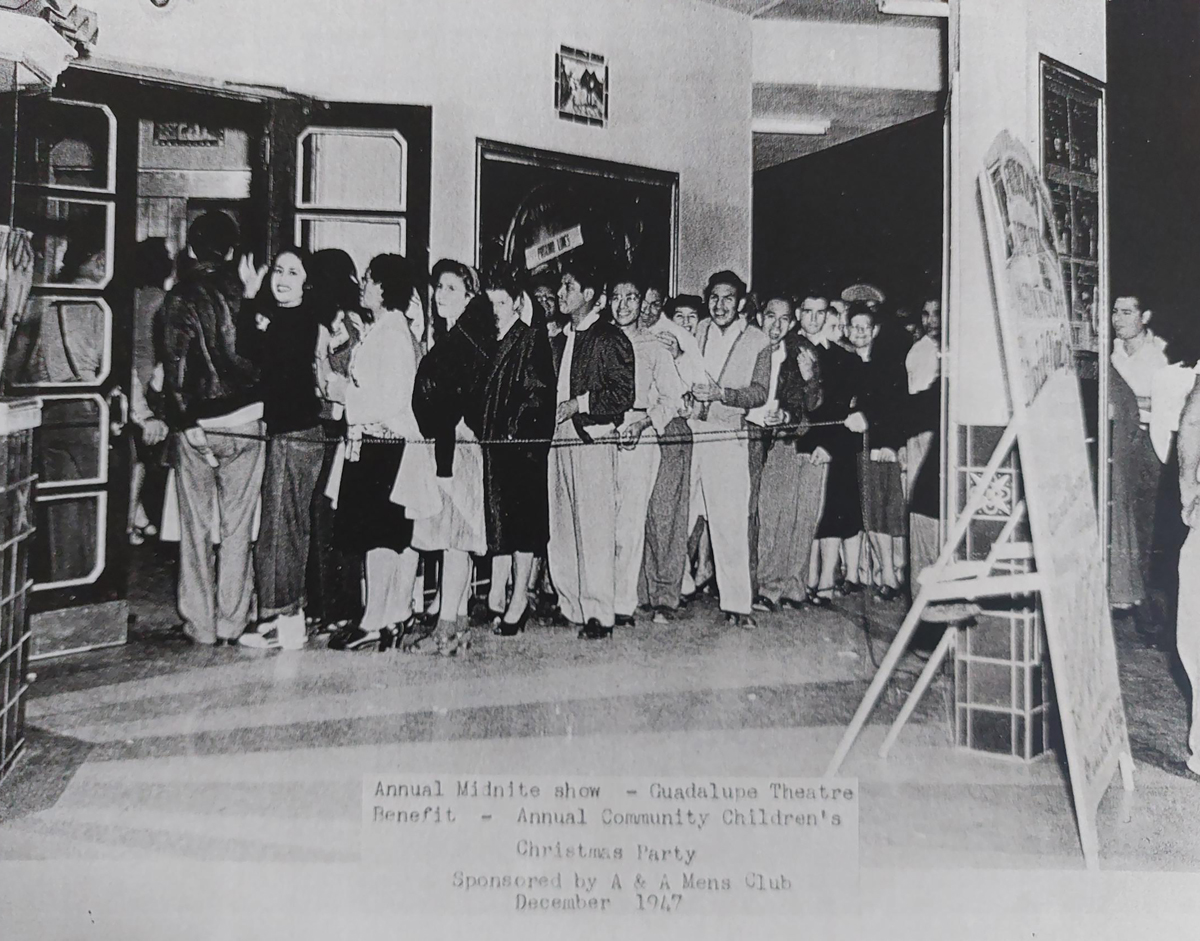

In its heyday, the theater showcased Mexican cinema and was a cornerstone of a thriving entertainment district along Guadalupe Street. But the neighborhood’s economic decline, brought on by systemic policies such as redlining and “urban renewal” projects—like the construction of highways in the 1950s and ’60s that isolated the Westside from downtown—ultimately doomed the venue. Teatro Guadalupe fell into disuse and later abandonment.

The revitalization in the early 1980s launched the cultural organization as it is known today: an active center for performing, literary, and visual arts. The beloved institution not only presents theatrical performances, art exhibitions, and major cultural events like the annual Conjunto Festival, but it also offers educational programming for learners of all ages in mariachi, conjunto music, folklórico, and flamenco.

This neighborhood was economically segregated and neglected for centuries so land was affordable.

“This neighborhood was economically segregated and neglected for centuries so land was affordable,” Cristina Ballí, executive director of the Guadalupe since 2016 explains, speaking to the long history of segregation in San Antonio that dates back to the Mexican-American War. “But more than anything the Guadalupe kept expanding its program offerings so it simply needed more space.” Over the years, the organization’s expanded campus has grown from its first office in the old Progreso Pharmacy across from Teatro Guadalupe to include six properties. “Decades later we understand what an important step it was to purchase land, and we now approach that more intentionally,” she says.

Among the Guadalupe’s properties are the old Progreso building, which houses the organization’s offices and its Latino Bookstore & Gift Shop, and two pastel-pink buildings a block north of the theater: the Guadalupe’s educational space and La Popular Bakery. Staples of the community, both buildings’ exteriors have been painted by local youth through San Anto Cultural Arts, an organization that believes in the power of murals to strengthen and energize communities.

Familia y Cultura es Vida, the mural on the side of the panadería, demonstrates well the struggles and triumphs of the area. It was first painted in 1995 on the wall of a Garachitos, a gas station that also served as a local gathering space. A sketch of a man working on his lowrider, drawn by then thirteen-year-old Debbie Esparza, fueled the imagination of Manuel “Manny” Castillo, an artist and co-founder of San Anto. Juan Miguel Ramos, also an artist and co-founder of the organization, stepped in to co-produce the project alongside Esparza, who had never painted before. The duo expanded the imagery of the mural to include an homage to the store owner, who often sat outside and played his accordion.

In 2008, the city condemned and demolished Garachitos, but three years later the design came to life again, this time on the bakery’s wall. The way San Anto managed this mural highlights its unwavering commitment to the community—trusting a young artist’s vision, supporting the creative growth of local youth, and, in spite of the blow dealt by the city, resolving to repaint a mural so steeped in local history.

The Garachitos mural was only the second one created by the organization that would become San Anto. In 1993, Castillo, Ramos, and fellow artist Cruz Ortiz, launched a community arts program as a project of Inner City Development, a nonprofit operating in the near Westside, where Castillo, who passed away in 2009, volunteered. Castillo drew inspiration from a mural program that transformed the Cassiano Homes, a Westside housing authority project, in the 1970s and ’80s, and a youth summer program run by La Casa de la Cultura in Del Rio.

Castillo, Ramos, and Ortiz focused on involving youth in community development through mural painting and the publication of a local newspaper, El Placazo. Four years later, the trio officially established San Anto as a separate nonprofit entity. In its thirty-two years, the organization has completed more than sixty murals and published over 230 issues of El Placazo.

Beyond the cultural output, San Anto has shaped the lives of countless young people, providing an outlet for creativity and helping them hone artistic, leadership, and community-building skills.

“Our programming is focused on fostering human and community development through community-based arts and that means people and community are the product of our programming more than the art we create,” Cuauhtli Reyna, the recently appointed executive director of San Anto, explains. “While our murals draw the eyes of a San Antonio that might otherwise not see us and El Placazo tells the stories of those often unheard, our programming is meant to strengthen and empower the youth and communities we work with to have pride in their barrio and preserve its culture for a better Westside we can all work towards.”

[These organizations] understand that art is much more than aesthetics. It is a dynamic source of empowerment and social change.

The Westside, often described as “the heart of the city,” pulses with life. Colorful murals adorn its walls and small, family-owned businesses line its streets, and yet, it is also one of the most impoverished parts of town. Community members face a slew of issues such as unemployment, high rates of poverty, poor health outcomes due to lack of insurance and availability of healthcare, low educational attainment, and more.

In this context, Esperanza, the Guadalupe, and San Anto are more than cultural hubs. They are interwoven in the fabric of the community and while each approaches the preservation of their neighborhood differently, they understand that art is much more than aesthetics. It is a dynamic source of empowerment and social change. San Anto has nurtured generations of young creatives. The Guadalupe preserves cultural traditions through its educational programming and purchases commercial property to keep it out of the hands of outside developers. Esperanza empowers the community and works to keep locals in their homes.

In the year since it was officially established, Esperanza’s land trust has saved one family from foreclosure by paying the property’s mortgage. Currently, it is engaging with other residents who need major home repairs and is making plans to update homes to be more sustainable. The trust also owns seven casitas it is currently renovating, with plans to rent to low-income residents.

There is surely a long road ahead for San Antonio’s Westside as development continues to encroach and city funds and priorities are stretched. But amid these challenges, these cultural organizations are a testament to the power of art, activism, and community. They are a reminder that creative community-driven solutions can affect change.

Editor’s note: This article was supported in part by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.