Santa Fe’s fifteen-year Rubber Lady project was a master class in fugitive—and funny—social subversion. At Vladem Contemporary, the artist unmasks herself.

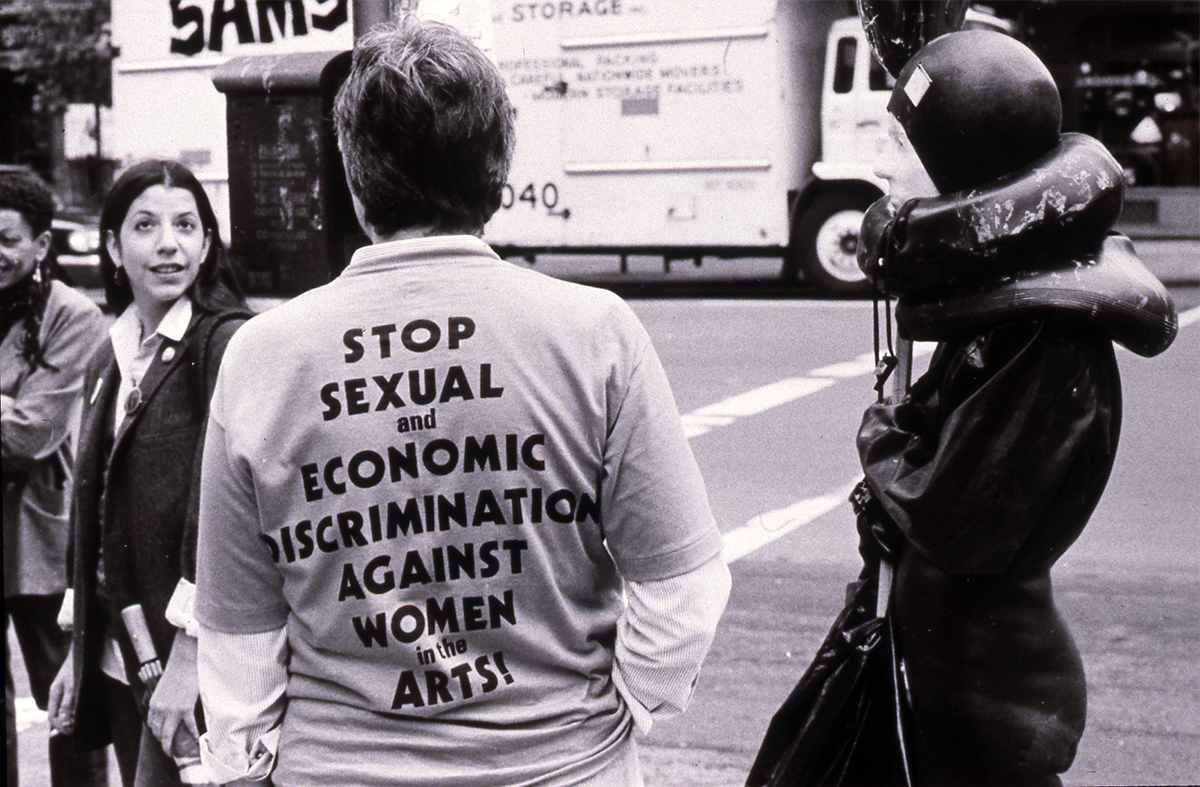

Anonymous art collective Guerrilla Girls donned gorilla masks in 1985 to criticize MoMA’s lack of representation for women artists. Leap back one feminist wave (from the third to the second), and Jacqueline Melega first shimmied into her own protest gear—a black rubber suit with an eerie white mask—in 1978.

Melega, better known as Jackie M, was a young museum worker in Santa Fe determined to oppose an act of censorship by her employer. Her daring first action launched about fifteen years of anonymous performances as the Rubber Lady, a social experiment that cast her as an avant-garde performance artist, children’s entertainer, and pretty much everything in between.

The Rubber Lady project ended in the early 1990s, but her mask has resurfaced in Off-Center, a group exhibition at New Mexico Museum of Art’s Vladem Contemporary—part of the institution she originally protested. In our current era, ruled by anti-DEI policies and arts funding cuts from an empowered “woke Right,” the Rubber Lady is a case study in playful and elusive social subversion: art as moving target.

I wanted to take on the characteristics of the material of rubber.

Jackie M revealed herself to be the Rubber Lady long ago (once in the 1980s, she told the press it was “Santa Fe’s worst-kept secret”), but my downtown meeting with her still feels a bit illicit. The Rubber Lady used to only talk to the press by phone, after they requested interviews through the local Grapevine Answering Service. She sports sleek gray hair, chunky frames, and an elegantly understated outfit—a perfect Santa Fe disguise. But she offers vast evidence of her bizarro alter ego: a blue file folder of press clippings and photographs, crowned by the Rubber Lady’s extensive CV.

Near the top of the CV is the Rubber Lady’s inaugural public performance, Meditation in Front of a Hidden Bomb Shelter, enacted during a reception at Santa Fe’s Museum of Fine Arts (now called New Mexico Museum of Art). The Rubber Lady entered the event with a basket of white chrysanthemums and laid it before a particular wall, which had been hastily erected to obscure an art installation of a 1950s-style bomb shelter by Roger Sweet.

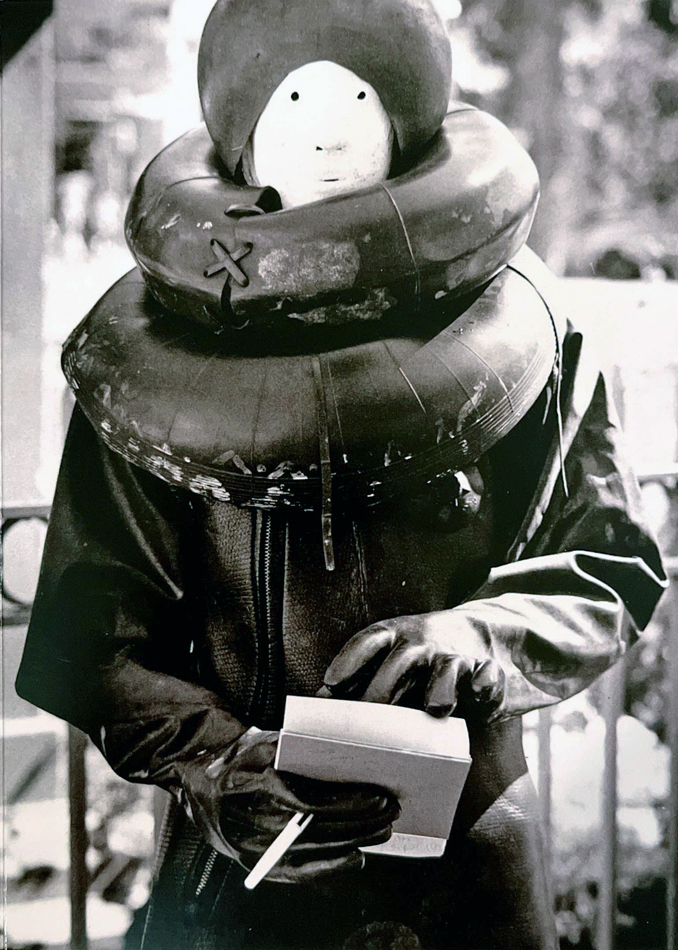

The hidden artwork was part of a cancelled show that museum leadership had attempted to edit due to an artwork by Bradford Smith that they deemed sexually explicit. The Rubber Lady’s action could thus be interpreted as a protest against the suppression of art, or sexual expression, or critiques of war and the Atomic Age. Jackie M tells me that the rubber suit, crafted by Smith from neoprene and airplane tire inner tubes, could also have been a Vietnam War commentary: “They always called it a war [against] communism, but it was a war for rubber—for natural resources.”

Whatever she may have meant, the Rubber Lady wasn’t talking: she was mute while performing, instead communicating through gestures or scribbles on a notepad with a black Flair pen. For the first performance, maintaining a secret identity was a protective measure: Jackie M was a part-time clerk in the Museum of Fine Arts’s gift shop.

“I wanted to take on the characteristics of the material of rubber,” Jackie M tells me. “In terms of the feminist thing, being flexible and responsive was considered to be a feminine quality at the time—we were supposed to be passive and creative, where men would be more out there, assertive.” The Rubber Lady would act as a vessel and mirror for society’s kaleidoscopic interpretations of her, nodding and miming along as spectators reacted to her with shock, desire, disgust, or joy.

And react they did, as Jackie M leveraged the interest generated by her inaugural performance into a flurry of appearances that at times filled a forty-hour workweek. The Rubber Lady surfaced in art contexts like galleries, museums, and the now-defunct Shidoni Foundry’s sculpture yard—but was also spotted on parade floats, at funerals, in department store windows, and at the Santa Fe Children’s Museum. She was a big hit with kids, who theorized about the origins of her squishy rubber skin and the contents of the black garbage bag she filled with props and merch (one boy deemed the latter “the Rubber Lady’s home,” and would grow distressed on garbage day).

Is Santa Fe weird, or just bored? [The Rubber Lady] must be some kind of Dadaist practical joke.

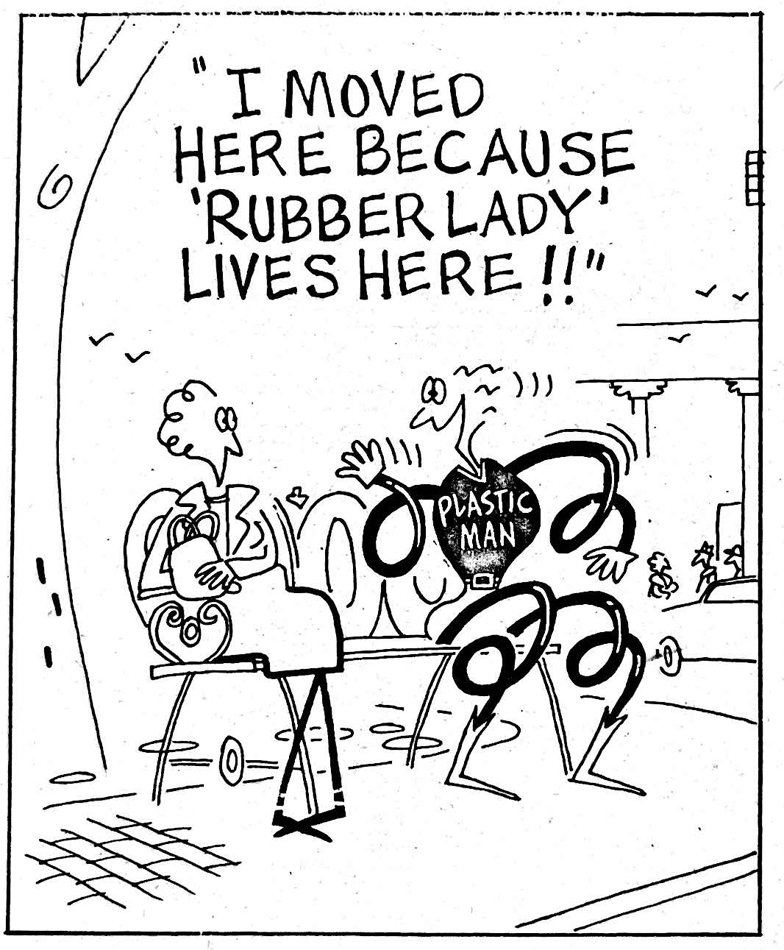

“Is Santa Fe weird, or just bored?” wrote Albuquerque journalist Ray Abeyta. “[The Rubber Lady] must be some kind of Dadaist practical joke on the artist’s exhibitionist tendencies.” Abeyta wasn’t the only person to ponder the Rubber Lady’s sexuality: she once met a rubber fetishist, who gifted her a rubber cape and told her about his loneliness. In another potentially covetous incident, Jackie M briefly misplaced her suit and it turned up in a bus station locker with a split seam, suggesting someone else took it for a spin.

In her anonymous interviews, Jackie M embraced it all, telling Pasatiempo on the Rubber Lady’s tenth anniversary in 1988, “I’m a reaction to a reaction. I’m seen as child-like, creative, a kook or as a walking rubber fetish. I wear many faces, it’s up to people to figure out which one fits their attitude.” By then, she had taken the project on the road, traveling to multiple U.S. states and across Mexico. She toured Elvis Presley’s Graceland and the Venice Beach boardwalk.

Jackie M’s wide-open stance on how to interpret the Rubber Lady, which was already feminist commentary in itself, allowed her to spin all sorts of other political content into her work. She handed out free artworks in the middle of a major exhibition; protested postal rate increases by distributing three-cent stamps on the street; dispensed condoms and HIV/AIDS prevention literature to University of New Mexico students; parodied American perspectives on developing nations from the front window of a bank; and attended a screening of a Billy the Kid film at the Santa Fe Film Festival. And she was still considered apolitical enough to grace children’s birthday parties.

The Rubber Lady petered out as social attitudes shifted in the early ’90s. “People used to cross the street to see the Rubber Lady, to bring their children,” Jackie M tells me. Suddenly, they were striding the other way. Jackie M shifted her focus to museum education; she had an award-winning tenure as the founding director of education and public programs at Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

However, the Rubber Lady’s spirit still hangs around—at times quite literally, as in Vladem Contemporary’s current exhibition Off-Center. Casts of Jackie M’s index and middle fingers dangle from a flattened Rubber Lady mask, literally placing her fingerprints on the project, and on a legacy of subversive conceptual art in Santa Fe. The Rubber Lady’s motto was a John Cage quote, after all: “Art as play and affirmation of life should wake us up to the very life we’re living—which is so excellent.”