Amid the escalating climate crisis, a dozen artists explore the impacts of human activity on the natural world during the Anthropocene era in Temporary in Nature at Lisa Sette Gallery.

Temporary in Nature

October 9–December 31, 2021

Lisa Sette Gallery, Phoenix

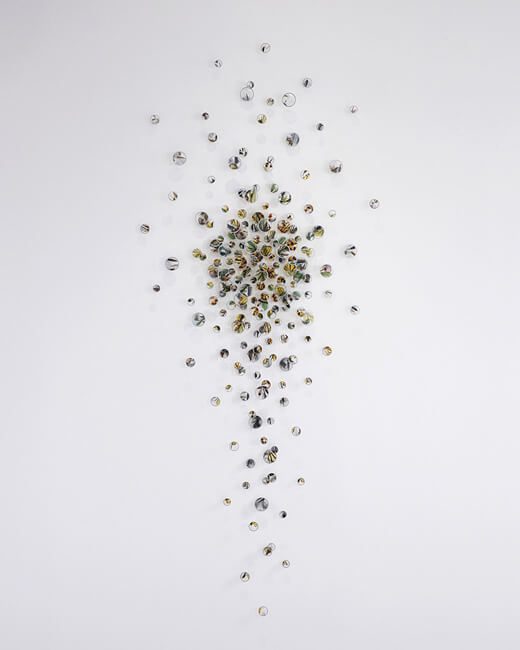

An orb within a human form signals the impact of human activity on the environment in Alan Bur Johnson’s a flock, a swarm, one of several works featured in the Temporary in Nature exhibition at Lisa Sette Gallery in Phoenix, Arizona. The installation comprises 183 photographic transparencies of bird, butterfly, and insect wings set in circular forms and mounted with dissection pins to allow for gentle movement reminiscent of collective flight.

The orb also speaks to the impact of the earth on human existence, suggesting the interdependence that’s often devalued or ignored by those living in the Anthropocene era, thought by many to have begun with the atomic bomb detonation in 1945.

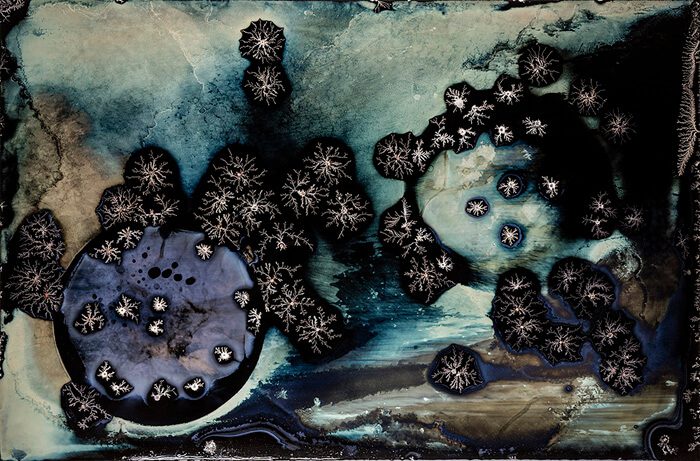

For Michael Koerner—an artist and chemistry professor whose collodion-on-tin photographs channeling mysterious biological forms are also part of this exhibition—that date holds particular significance. His mother was twelve years old and living in Nagasaki, Japan at the time. His father served on a United States Navy ship near the site of numerous nuclear experiments.

With his crystalline blooms on black lacquer backgrounds for a series called Cherry Blossoms, Koerner tells the stories of his parents and siblings, each of them deceased due to cancer or genetic disorders. Here, the exhibition amplifies the real-world impacts of human decisions and actions rather than offering a merely theoretical construct, or simply elevating a sentimental, romantic view focused only on nature’s beauty.

Collectively, these artists offer a quiet meditation on what’s at stake while prompting reflection on ways individuals and communities can work toward shifting the perilous trajectory of the current geological epoch.

Several exhibited photographs examine physical changes in the natural landscape wrought by human intervention, conveying the myriad motivations behind them.

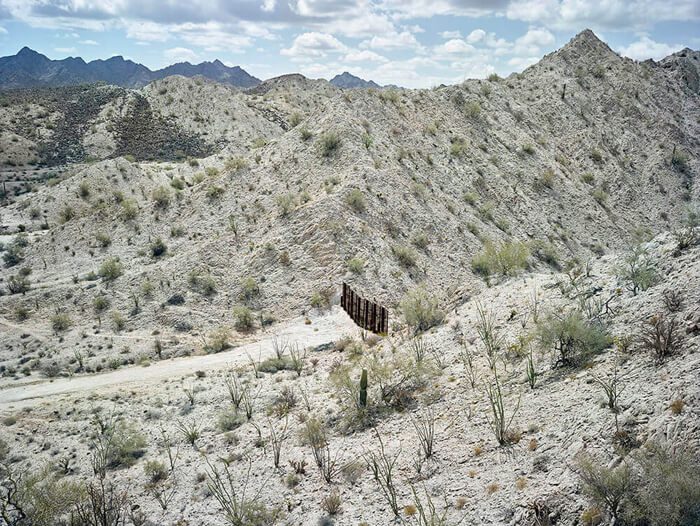

Mark Klett highlights the absurdity of attempts to exert control by creating artificial boundaries with Fence Separating the US/Mexico Border South of the Gila Mountains, May 2015, a 2015 pigment print showing a solitary gate in a vast expanse of desert.

Matthew Moore’s Rotations: Moore Estates 3 suggests the ways development is encroaching on farmlands. Moore is both an artist and a fourth-generation farmer, and his c-print shown here provides an aerial view of a thirty-five-acre project planted with sorghum and wheat.

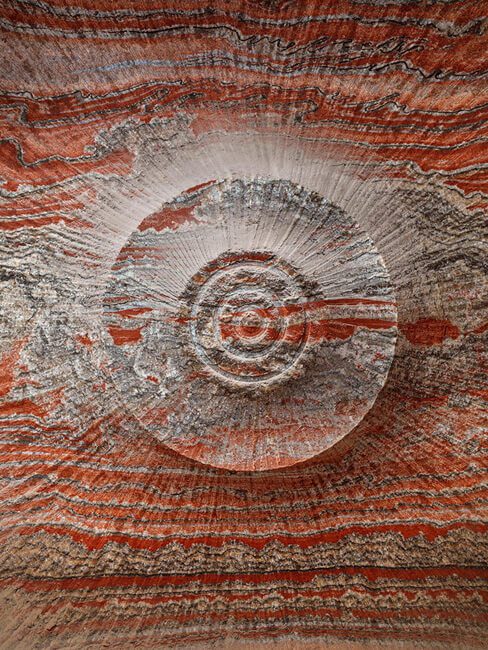

Concentric rings of multi-hued earth resulting from extraction appear as a stunning design in Edward Burtynsky’s Uralkali Potash Mine #3, Berezniki, Russia, yet the rings captured in his aerial photograph allude to destructive forces behind much of the world’s manufactured beauty.

Similarly, Yao Lu’s photo collage (New Landscape part I-06 View of waterfall with rocks and pines) featuring industrial refuse piles covered by green netting, presented in the style of traditional Chinese landscape paintings, critiques consumption-based culture. The piece also compels viewers to bring a critical eye to observations made both within and beyond the gallery walls.

Some works explore the human impulse to leave a literal mark on the world, focusing on the creative drive that fuels artistic endeavors.

For example, the exhibition includes an aerial survey and site plan for James Turrell’s Roden Crater, a monumental work he’s been developing in the Arizona desert for more than four decades. Photographs of Robert Smithson’s 1970 earthwork Spiral Jetty, taken in Utah by artists Michael Lundgren and Binh Danh, are shown here as well.

Other pieces elevate familiar elements of the natural world such as leaves or drops of water.

Photo constructions by Marie Navarre present tear-shaped forms that suggest both raindrops and tears, alluding to emotional connections in nature, while Binh Danh’s photogram centering the haunting image of a leaf speaks to the transience and the fragility of life.

Kim Cridler’s sculptural tree stump created with steel, twenty-two-karat gold, and silver includes concentric lines that reference interior growth rings. But these lines also appear as a metaphysical entry point into the cosmos or a human fingerprint, speaking to connections that transcend temporality.

Despite the poignancy of particular pieces, Temporary in Nature falls short of conveying the growing sense of urgency at the heart of contemporary conversations about the demise of the natural world at the hands of humankind.

There’s one notable exception: a trio of works by Mayme Kratz, whose art practice includes foraging for natural elements she meticulously arranges and sets in resin.

The exhibition includes two pieces from her new Vanishing Light series, in which plant materials are arranged into circular forms. Dark circles at the center of each botanical design resemble pupils of the eye, seemingly witnessing both minute and monumental changes in the environment.

Inside a small alcove within the gallery, viewers encounter Kratz’s Ghost Forest with suspended vertical branchlike forms resembling barren trees. Like the exhibition as a whole, the haunting forest serves as both a cautionary tale and a call to action.

Temporary in Nature continues through December 31, 2021 at Lisa Sette Gallery, 210 East Catalina Drive in Phoenix.