Shonto Begay: Eyes of the World and Indigenous Women: Border Matters at the Wheelwright in Santa Fe foreground connections to place.

Courtesy Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian.

Shonto Begay: Eyes of the World and Indigenous Women: Border Matters

April 10–October 3, 2021, and March 20–October 3, 2021

Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, Santa Fe

Centering artists’ voices, two current exhibitions at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian foreground connections to and experiences of place. Engaging historical consciousness, cultural memory, contemporary politics, and personal agency, Shonto Begay: Eyes of the World and Indigenous Women: Border Matters work together to reorient the viewer to alternative perspectives and narratives in the Southwest.

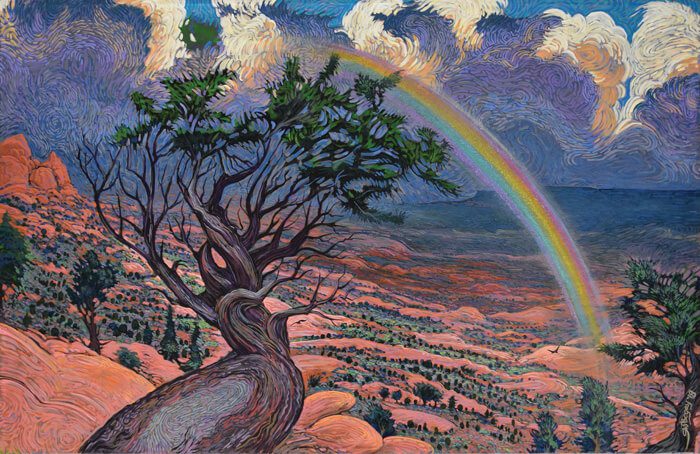

Curated by the Wheelwright’s 2019-2021 Andrew W. Mellon Foundation curatorial fellow Zachary Miller (Chickasaw), Shonto Begay: Eyes of the World highlights Begay’s uniquely Diné way of seeing. An exhibition with more than forty works from the “Navajo Neo-Impressionist,” Eyes of the World seamlessly moves between discussions of Diné sense of place, cosmology, and history.

Each gallery introduces the viewer to a different side of Begay’s work. The first room deliberately situates the visitor within the artist’s worldview—stunning images of Dinétah are put in conversation with portraits of Navajo individuals and communities, demonstrating the ways in which Diné life is shaped by and through connection to landscape and home. In this area, the striking Promise of the Coming Storm (2018), brilliantly depicts the Shonto Plateau:

This land carved features into my character. This land gave me lessons on life and how one should speak with her. It is the land where I smell rain days away, a curtain of dust miles off in the distance as a dry wind sweeps the valley floor below me. […] This is the land I know well.

As shown here, one of the exhibition’s core strengths is the way in which Miller leads with the artist’s voice and interpretations of his own practice. This strategy, alongside the organization of the exhibition, urges the visitor to view the body of work as an expression of worldview, rather than an exhibition of a particular subject.

From here, the show turns to Diné cosmology and ways of knowing. This space provides the viewer a unique perspective on the trajectory of Begay’s practice—the ink on paper Hero Twins Series (1980) is next to the monumental acrylic painting, Hero Twins on the Edge of Creation (2016).

After situating the visitors within both Navajo landscapes and origins, the exhibition moves to portraits of everyday life in Dinétah. In particular, Drawn by the Light (2018) provides a stunning glance into the beauty and centrality of Navajo ranching. Seamlessly alternating between these landscapes and portraits to frank discussions of historical trauma and settler-colonial violence—boarding schools and Bosque Redondo in particular—this section makes Diné histories and ways of knowing accessible through clear and honest curatorial interpretation.

Aptly named, Eyes of the World is a profound glimpse into the way an artist sees their surroundings. And foundationally situated within a uniquely Diné sense of place, the exhibition asks us to reflect on our own trajectories within landscape, home, and community. How did you come to be where you are?

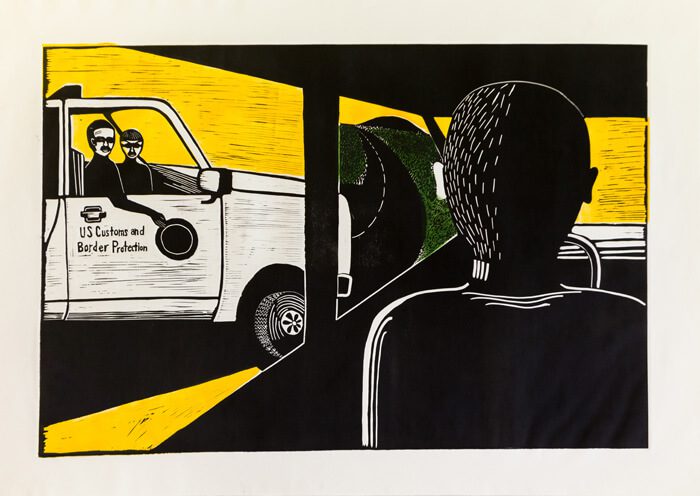

In the following gallery, Indigenous Women: Border Matters brings the narratives, voices, and lived experiences of four women artists on both sides of the United States-Mexico border to life.

Curated by Andrea Hanley (Navajo), Border Matters provides a lens from which visitors are prompted to think critically about the construction of the so-called United States and the violence inherent within. Reflecting on their individual experiences living in the borderlands, the artists collectively move between celebrating survival and the realities of suffering within this landscape.

Opening the exhibition, Makaye Lewis’s (Tohono O’odham) monotype and linocut pieces reflect on immigration, belonging, and the ongoing effects of settler colonialism on her O’odham homelands. In the striking Remembering When They Laughed at My Dad’s Disability (2019), the viewer is asked to shift their perspective and tangibly feel the daily violence inherent within the systems and actions of the United States Border Patrol.

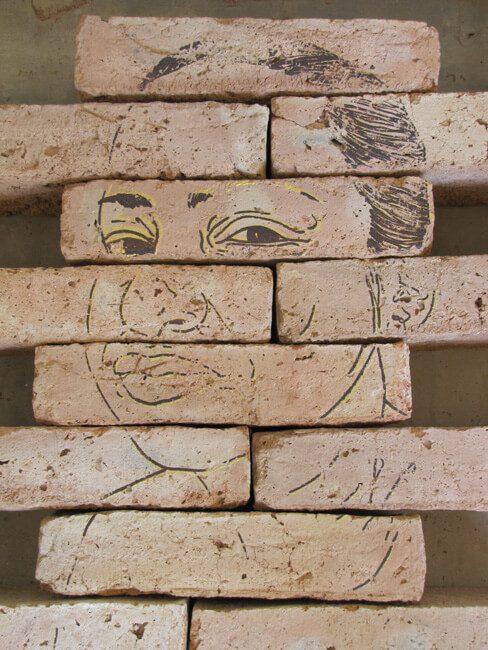

Anchoring the exhibition is Gabriela Muñoz (Latinx) and M. Jenea M. Sanchez’s (Latinx) Labor/Retratos 1 and 2, Mujeres de DouglaPreita Trabaja (2016), a serigraph on handmade Mexican bricks. This installation “[d]epicts Indigenous women who are a part of DouglaPrieta Trabaja (DPT), a women’s collective in Agua Prieta, Sonora, México. The sculptural portraits pay homage to the ways in which women of color can lead horizontally. The bricks reference the collective’s power to build their own futures, both figuratively and physically.”

Also from Muñoz, the Brown on Brown Series, Licha, Lonrena, Josefina, Rosalinda, Doña Trini, Maty (2018) again celebrates the women of color who are embedded within and lift up their communities. This collection of serigraphs was created with breast milk and Mexican earth on handmade paper made from saguaro, cholla, yucca, and migrants’ clothing, reminding viewers of the unique spatial and physical contexts these women are living within. Together, these two bodies of work celebrate the agency, power, and leadership of women of color along the border.

These energizing works are juxtaposed with Daisy Quezada Ureña’s (Mexican-American) Arbol de Violencia, 2nd Series, No. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10 (2020). Translating to “Rape Tree,” this incredibly poignant and immensely provocative installation of porcelain and acrylic sculptures again asks the visitor to shift their perspective—what particular types of violence do women experience when crossing the border? In the audio guide, Quezada Ureña describes her process and intention—“the piece once held by a body now holds itself, evoking the absence of the individual.”

Leaving the visitor wanting more, Border Matters is a call to action—urging us to think critically and reflect deeply on the realities of la frontera, and own our place within settler colonialism, imperialism, and the structures of harm.

Engaging politics, historical narratives, and personal experiences of identity—all while staying grounded in a sense of place—together, Eyes of the World and Border Matters mark a key moment for the Wheelwright.