The 2021 Texas Biennial explores cross-sections of identity and project optimism in A New Landscape, A Possible Horizon across five venues in San Antonio and Houston.

2021 Texas Biennial: A New Landscape, A Possible Horizon

September 1, 2021–January 9, 2022

McNay Art Museum, San Antonio

August 19–December 5, 2021

San Antonio Museum of Art

Other 2021 Texas Biennial Dates and Venues

September 2–November 13, 2021

Fotofest, Houston

August 5–December 26, 2021

Artpace, San Antonio

August 5, 2021–January 31, 2022

Ruby City, San Antonio

When viewing Roni Horn’s The Gold Field in 1990, Félix González-Torres was moved by the reflective and uplifting qualities in the work, proceeding to describe it as “a new landscape, a possible horizon…” The simple gesture of Horn’s flat gold mat sparked González-Torres to ponder the prospect of transformation in a seemingly hopeless social and political climate amid the HIV/AIDS crisis.

This poetic utterance, borrowed from González-Torres in the title of this year’s Texas Biennial, serves as a stimulus for approaching the work of fifty-one artists, bearing visual testimony to recent demonstrations to protect Black, transgender, Asian-American, Pacific-Islander, and immigrant lives.

Sponsored by Big Medium and curated by Ryan N. Dennis and Evan Garza at five different venues in San Antonio and Houston, 2021 Texas Biennial: A New Landscape, A Possible Horizon presents works by Texas-based artists and “Texpats” selected for their ties to the Lone Star State. The biennial is dispersed across five venues, including Fotofest in Houston (which closed its 2021 Texas Biennial exhibition on November 13) and Artpace, Ruby City, San Antonio Museum of Art, and the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio.

A triptych of paintings entitled Sad Girls (2021) by Jasmine Zelaya along with When He Believed She Could Never (2021), Abhidnya Ghuge’s large sculptural installation, greet visitors at the SAMA entrance. Both artists explore organic forms, playing with existing contrasts between the natural and artificial worlds. In her paintings, Zelaya depicts the faces of three women, their eyes red and brimming with tears, while the remainders of their facial features are erased or masked by flowerlike forms. Ghuge’s sculpture—constructed of 8,807 paper plates and eleven saris in a fiery palette held together by wire armature—blooms into otherworldly foliage.

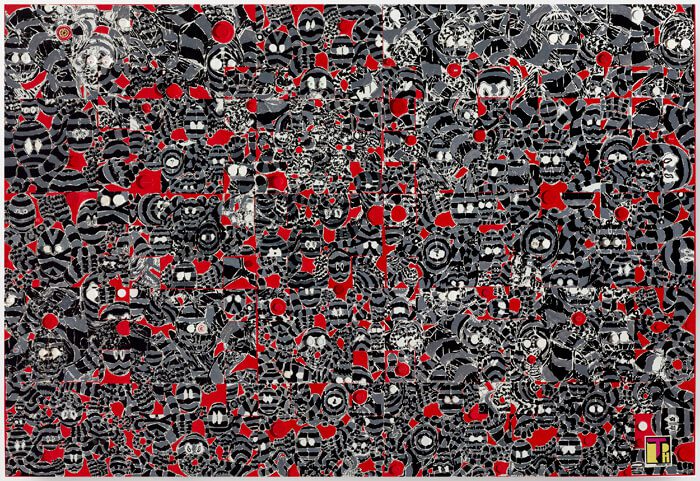

Upstairs, the main gallery space displays prints, photographs, a video, and paintings from a group of artists including Rick Lowe, Tomashi Jackson, Trenton Doyle Hancock, Vincent Valdez, and others. These works frame a central installation by José Villalobos, an upcoming 2022 resident at the Joan Mitchell Center in New Orleans.

The title of Villalobos’s 2021 work Los Pies Que Te Cargaron translates to “the feet that carried you”—a pair of dirty concrete feet appear in the center of a neatly compacted soil base. Ropes extend from the ghostly appendages and, in an impressive act of trompe l’œil, appear to support the weight of a rhinestone saddle. Five plaster hands, tied to the ropes attached to the feet, extend to each corner of the dirt platform. The fingers grip the earth in response to erotic stimuli or as an act of self-preservation driven by fear. The work plays with gender expression with a rugged leather saddle bedazzled in pink and purple sparkles, asserting a different declaration of Norteño experience rejecting machismo.

At the McNay Art Museum, three extensive galleries display artworks and installations by a large roster of artists and art collectives, including Donald Moffett, John Gerrard, Steve Parker, and Filipinx Artists of Houston. In addition, emerging artists Ari Brielle, Xavier McFarlin, and Irene Antonia Diane Reece installed large-scale mixed-media works highlighting personal experiences of family, gender, and race.

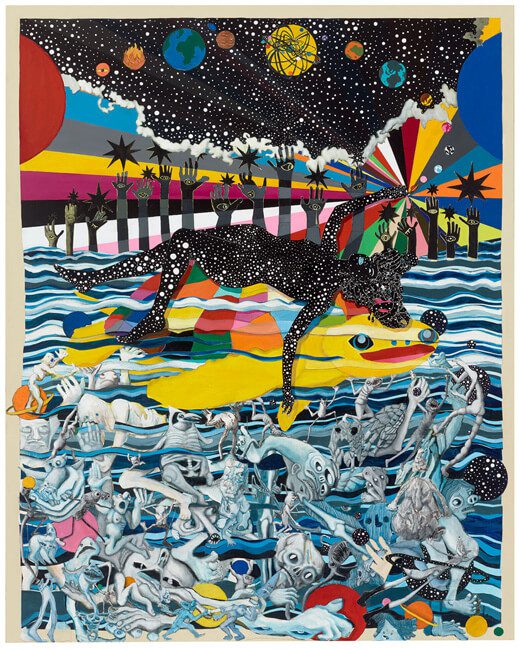

Similar themes emerge in the work of multimedia artist JooYoung Choi in her video installation Journey Vision 5000-Pangolorian Edition (2018) and painting Tourmaline the Celestial Architect (2019), both proposing an alternative reality of imaginary friends and childhood utopic escape. Both works belong to the Cosmic Womb, a world built by Choi to reconcile the autobiographical with the fantastical. Her painting Tourmaline the Celestial Architect (2019) includes a technicolor turtle ferrying a stellular passenger across waters infested with undesirable ghouls—the sky torn open, revealing this setting as an alternate life-supporting planet in the same universe as Earth.

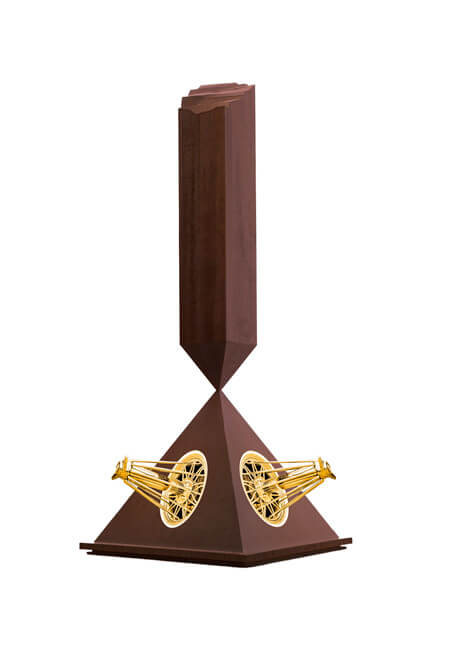

In addition to works serving as a means of worldbuilding for “a new landscape, a possible horizon,” other artworks propose or offer reimaginings of monuments. For example, Houston artist Phillip Pyle, II updates Barnett Newman’s pillar at the Rothko Chapel in his print Broken Obelisk Elbows (2018). Pyle’s digital rendering includes gold swanger rims, a crowned icon in Houston car culture and a revered reference in Southern hip hop music. In amending the original work that Newman created under the context of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, Pyle proudly asserts a twenty-first-century proclamation of Black excellence thriving.

Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello’s Teeter Totter Wall (2019), a video contained at the beginning of the McNay exhibition, perhaps best encapsulates the title of this year’s Texas Biennial. The hot pink seesaws pierce the United States-Mexico border wall. Between El Paso and Ciudad Juárez, children activate the installation on both sides of the political boundary. While the teeter-totter may operate as a byproduct of the innocence of childhood play, the gesture punctuates current issues in the concept of national borders and refutes deductive assumptions about identity to transcend the present—and envisions a future where people treat each other with more compassion.