In this day of broad familiarity with Philip Guston’s figurative paintings, it’s hard to comprehend the shock of his 1970 show at Marlborough. Remember, though, that by then Guston, first a muralist and then a part of the New York School, had been painting his gestural liquid masses to much acclaim for over twenty years. The lead-up to Guston’s return to representational painting in the U.S. was marked by political assassinations at home and a rising death toll in the American Vietnam War abroad. His new approach to painting was not well received. In the face of this broad rejection, the self-assured Guston left the states for a seven-month trip to Italy to reconnect with Italian masters (Giotto, Masaccio, Tiepolo) and settled at the American Academy, where the Roma paintings emerged. In some paintings, Guston’s Ku Klux Klan hoods (repeatedly used in his politically aware paintings) crossed the Atlantic as stowaways, and in others, new subject matter started to become visible out of the rubbled mounds of Western antiquity.

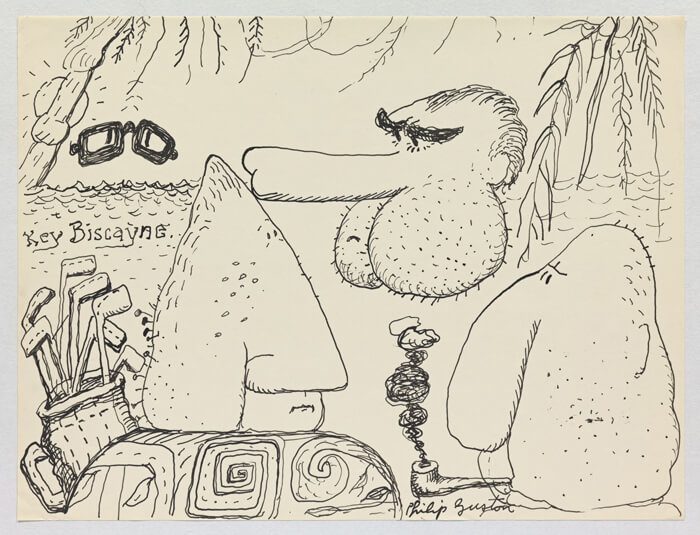

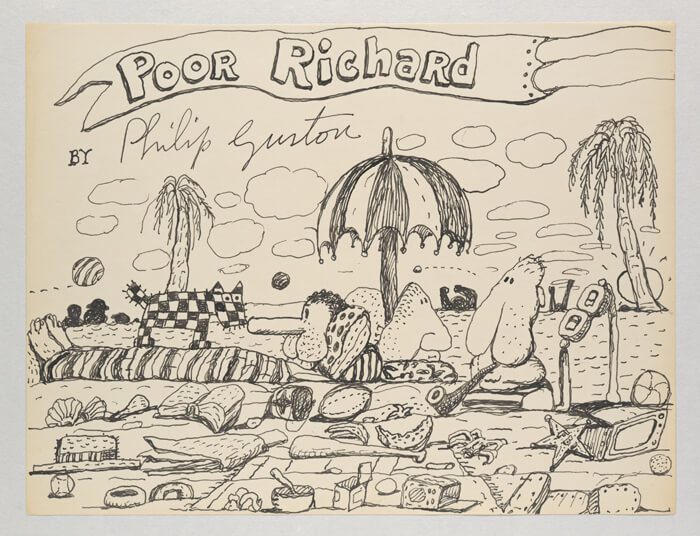

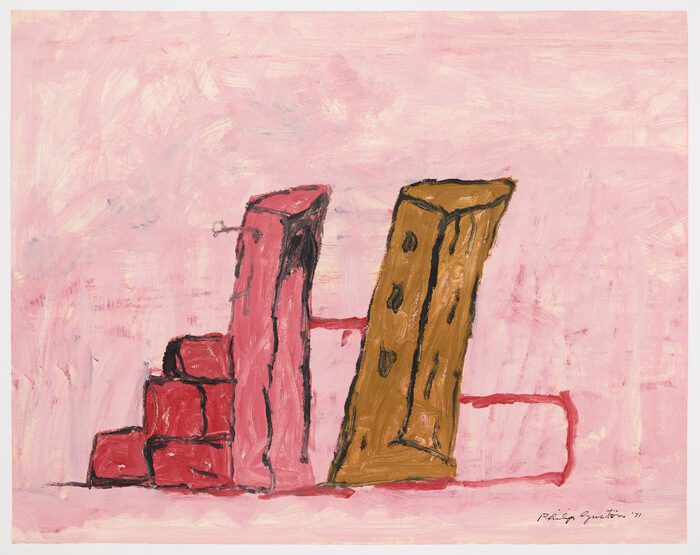

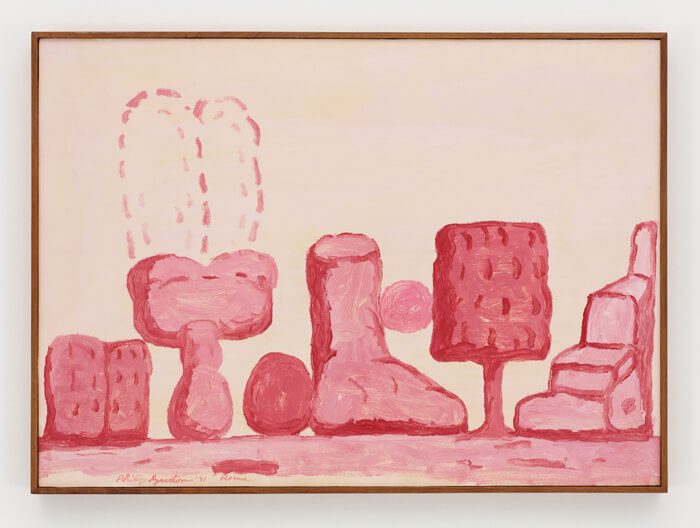

The Roma paintings, all works on paper and occupying the first two galleries of Resilience, feature garden scenes, stacked bricks, isolated feet, and neatly arranged objects rendered with the weighted charm of Guston’s hand. The Colossus of Constantine body fragments at the Musei Capitolini come to mind immediately as I stand in front of a sequence of foot paintings. Three of the paintings are squarely flat-footed, one with heel raised and weight shifted to the front, all with a mix of Guston’s red-tinted hues, larger-than-life scale, and deliberate, searching cross-contour brushstrokes. The ghost of Giorgio Morandi occupies a number of still-life arrangements featuring a line-up of cascading fountains, bisected ziggurats, stony feet, balancing balls, and manicured trees. A documentary filmed in Guston’s Woodstock studio with poet Clark Coolidge shortly after Guston returned from Rome was telling, but forgive my amnesia, as I was in a trance studying the neatly arranged boxes of oils, bundles of brushes, full painting racks, and his painting set-ups. And Camel Lights. Guston was definitely puffing on Camel Lights throughout his conversation with Coolidge. Also up are a dizzying number of satirical ink drawings critiquing the life and policies of Richard Nixon that Guston made in response to regular visits with Philip Roth. In an imaginary presidential tour of Beijing, Nixon, illustrated as a leaky hose and scrotum, darts across the Forbidden City in a convertible with Kissinger, represented as a floating pair of blocky eye glasses. This museum-grade exhibition captures a distinct pivot in Guston’s studio and lays the foundational approach to his final decade of painting.