Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, the renowned New Mexico-based poet, opens up about her personal poetry process and collaboration across artistic disciplines.

While hidden away in rural Northern New Mexico, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge has made a name for herself in the writing world and become somewhat of a local legend. Her most recent book, A Treatise on Stars, was awarded the 2021 Bollingen Prize for Poetry and was a National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize finalist.

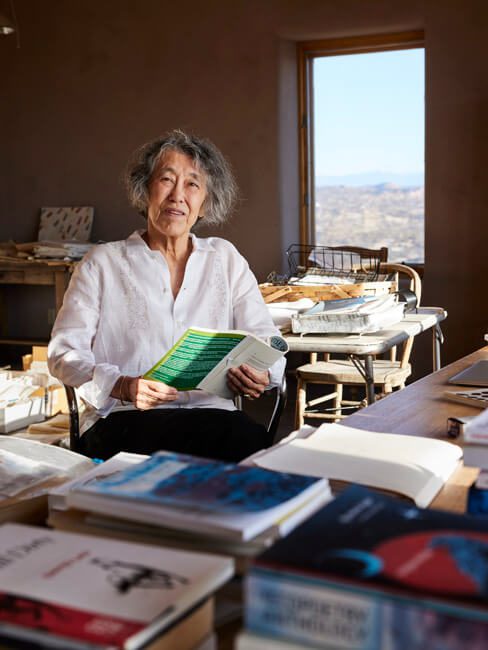

On a brisk, autumn afternoon I headed north, driving through dense cloud formations and stark high desert terrain to speak with the renowned poet. Looking out from her property, which is located atop a mesa that offers undisturbed vistas for miles around, it was easy to see how the natural world seamlessly makes its way into her poetry.

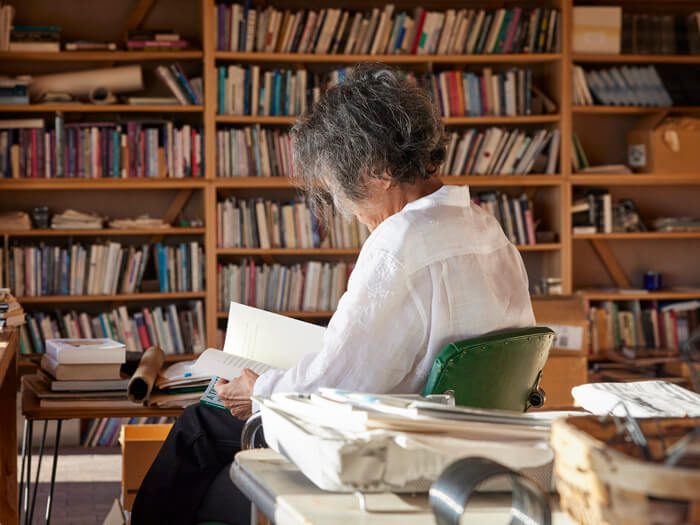

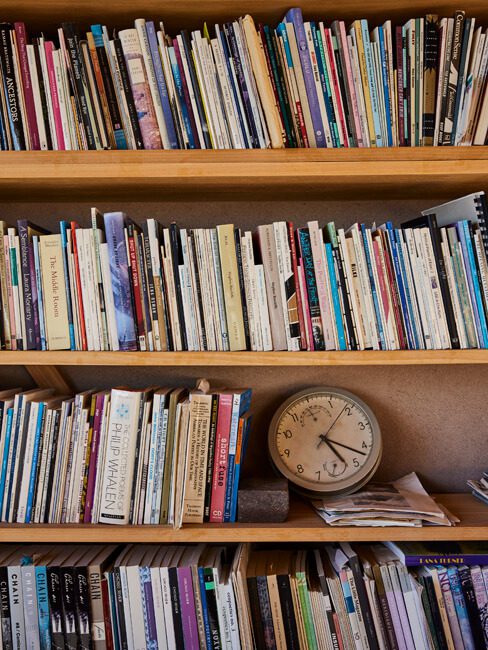

We sat and conversed at a long wooden table in the main sitting room, with generous picture windows on one side and a wall of books on the other. Berssenbrugge, who was deeply attentive and quick to smile, carefully considered her responses while gazing out at the expansive view of Abiquiú basin, the Pedernal, and sprawling mesas and mountain ranges. This interview has been edited for clarity.

What first drew you to New Mexico?

I first came to visit with a friend from Reed College, during school holiday in 1970. We drove all over, and it was love at first sight. That is a story many people will tell you. After that, I visited often. When I finished graduate school in ’74, I moved to El Rito, and I’ve been in this area ever since.

What has kept you here?

I think what has held me is the way the land and the people live together. And also the light, the way sunlight moves across the land, articulating a wide space, every day differently. I sometimes feel that I’ve had a history or a relationship here from before, from another lifetime.

Do you feel like this is your community?

I was part of a wonderful community of poets and artists in the ’70s, who worked for the New Mexico Arts division teaching poetry in public schools and prisons. We traveled all over the state, wherever we were invited. The two people who directed the program were former rodeo riders as well as writers and there was a deep love for New Mexico and its communities. One of the most talented students I ever encountered was from the New Mexico Boys’ School [now the Springer Correctional Center], in Springer. Even though I’m a solitary person, I appreciate and am grateful for the depth of spirit of the creative community in New Mexico and its diversity. I like that crafts interweave with and flow into the “fine” arts. I like that spiritual qualities are widely acknowledged.

I know that you went on to teach at the Institute of American Indian Arts. What was that experience like?

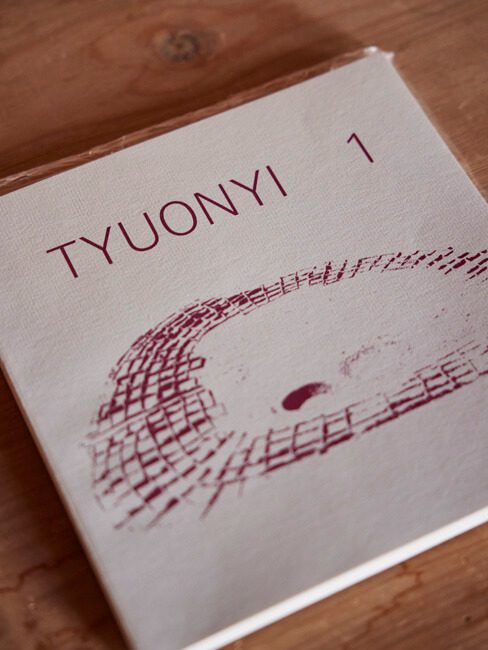

I taught at IAIA in the ’80s. It was another very free-wheeling, open, inclusive institution at that time. I remember IAIA hosted an Iranian architect who had developed a way to construct affordable architecture for a town, hardening the mud houses all at once by setting them on fire. There was a residency of Tibetan lamas teaching sand painting. There were Native American scientists and anthropologists and fashion designers teaching. So many were pioneering in their fields, so it felt adventurous and creative as a community. And the students were talented. Perhaps IAIA still has some of this feeling today. We founded a magazine called Tyuonyi in ’85, focusing on experimental poetry from diverse cultures. I worked with Philip Foss and Joy Harjo and Arthur Sze, among many others. I was very grateful to work there.

Is place important to your work—that is, not just the geographical location you reside in, but also your physical workplace?

I’ve often said my long lines evolved from the wide horizons of the high mesa country, and also from the arc of the sun across the landscape in front of me. Physically, for my workspace, I need a window where I can watch this light. In the morning I work in a small room with a south window, and move to a west window in the afternoon. When I compose, I use a large table for my notes. Walking and looking out from the mesa are also part of my work process.

I’ve heard you talk about your process when you work, which involves cutting out and arranging lines, and sometimes photographing them. Can you say more about that?

Yes, it’s a way of getting outside of my own head and into a wider area to compose from. I choose four or five books on a subject or question I’m interested in. Right now, I’m going back to the subject of plants, and I love to read books about people communicating with plants or listening to what plants have to say and how plants help us. Then I underline lines or sections that strike me. In a way I’m reading with my unconscious. I copy everything I’ve underlined into my laptop and print it out and cut out lines that interest me and spread them out on this big table and arrange them, often including visual images. I compose from my arrangement of notes, like a map. This used to be closer to a kind of appropriation, but lately the notes have become more of a scaffolding for the poem, and the actual words are changed a great deal.

If I can think of a poet who toes the line between poetry and art in their work, it would be you. Even your creative process feels like creating art. For you, is there a distinction between poetry and art?

I’m visually transforming the field of composition by physically placing the notes across the table. It does resemble an art process, because I use the notes as physical materials, and it’s a kind of collage method. The visual arts have always been a source of inspiration and energy for me, because I think of what one sees as extending outside the confinement of self.

Friendships with visual artists have been important. One of my books is called I Love Artists. I think this discourse and engagement that was separate from my own field gave me more freedom. When I was young, the field of poetry was conservative, and artists were engaging with newer ideas of culture and philosophy, which I could assimilate into writing. In the Akashic field, the arts are all continuous with each other.

You have collaborated with other artists, namely your husband Richard Tuttle and Kiki Smith. How has collaboration informed your work?

I lived in El Rito by myself into my forties. Collaboration became a kind of community for me. I immerse myself in the artist’s work, and then try to create a space in front of me for that artist to come into. I’ve collaborated in theater with Frank Chin, Alvin Lucier, and Tan Dun; in dance with Blondell Cummings and Theodora Yoshikami; as well as the visual arts. It was a way to have a family, or have relationships when I was at the same time living as a solitary person.

The experience of reading your poems in a book is rather hypnotic, partly due to the way the long lines pull the eye across the page. It makes me think about our changing relationship to reading through the infinite scroll of the vertical screen. Have you thought about the horizontal effect your poems have on the reader versus the vertical effect we seem to be moving toward?

That’s really interesting. I’m still very attached to the process of reading from the physical object of the book. It has something to do with the three-dimensionality and object-ness of words and the way information comes into my brain. I think there’s also a difference in how information comes to me—if it’s backlit or if light falls onto the words.

The physical object of the book has always been wonderful to me. Richard also works intensely in the book arts, and we share a dialogue of graphic design, materials, print qualities, layout, the sequence of your experience of poetry or art as you turn the pages. He has talked about the book as a kind of a body. My first collaboration with Kiki Smith was about the endocrine system. She used a Nepalese handmade paper that was somewhat transparent, so you could see through to other images, as you turn the pages. In that case, it was like seeing organs through the depth of flesh of the body. The cover is like the skin.

Your poems feel highly meditative, especially in A Treatise on Stars. Do you engage in a meditative practice?

I’m an anxious person, so I don’t meditate as such, but I need a lot of time to think. Walking and solitude are my way of meditating. I try to connect with the spirit of where I live.

Are you working on anything now?

After finishing Stars, I’ve returned to explorations from my previous book, Hello, the Roses, immersing myself in the spirituality of plants.

I have this idea that my generation was involved in an East-West cultural axis when we were young, for example, our interest in Asian philosophies. That has slowly transitioned to a North-South cultural and energetic axis. This energy has been calling to me through plants and forests from the Pacific Northwest to the Amazon. When Richard exhibited in Lima, we made several trips to Peru. The vast forests, the plants, the relationship between plants and weaving, the structural use of color in textiles—those kinds of ideas along with the way other peoples and cultures live with plants interest me. I’m trying to connect the beauty of fractals with the beautiful energy of growing. I don’t know how I’m going to interweave this research with my experience here, living with extended drought in New Mexico.

Green plants are a vehicle for me to express a way forward from the intensity and struggle of this period. I want to acknowledge the struggle, while connecting the openness of Stars with this force of great change that has introduced itself.