Abstract painter Agnes Martin sought isolation in New Mexico to stoke her obsessive practice. She found vibrant community.

The news spread through the small town of Taos: Agnes Martin was free for lunch dates. The Canadian American painter had cultivated an air of mystery in New Mexico for decades, having left New York City just as her art career was skyrocketing in the late 1960s. Now it was the ’90s, and the octogenarian lived in a retirement home and painted in the mornings, but presided over a table at the Trading Post Café each afternoon. She regularly picked up the tab.

“Once the word got out—you could have lunch with Agnes Martin—people started literally flying in from New York City,” says Karen Yank, a sculptor who was Martin’s unofficial protégé. “This one woman came up and kissed her on the lips and said, ‘I just love you.’”

Martin’s openness felt miraculous because her public image was so stark. Years before, following a series of creative breakthroughs in New York and an epic road trip, she’d landed atop a mesa near Cuba, New Mexico. She was halfway through her fifties and had finally established herself as a focal point of New York’s burgeoning art market. In the Southwest, she gave up painting—and, in her telling, people—for seven years.

I thought I would withdraw and see how enlightening it would be. But I found out it’s not enlightening.

“A lot of people withdraw from society, as an experiment,” she said later in a 1989 interview with art historian Suzan Campbell. “So I thought I would withdraw and see how enlightening it would be. But I found out it’s not enlightening. I think that what you’re supposed to do is stay in the midst of life.”

And yet, even after her wildly successful return to painting, exhibiting, and lecturing, Martin’s reputation as solitary and sage-like only deepened. The legend was fed, in part, by her obsessive practice: she’d burned most of her early work at the end of her near-decade in New York, devoting herself to the grids and stripes that seemed to flow beyond the edges of her mature canvases. She’d fill pages with equations, painstakingly plotting each six-by-six-foot composition, but the softly hued results were transcendent—“very like the relationship of rain to the ocean,” wrote artist Ann Wilson.

“If a painting wasn’t going well, Martin would quickly take a knife to her canvas,” reports Prudence Peiffer in The Slip (2023), a history of Martin’s New York circle. “She could not stand to have things around her that didn’t work. A term that comes up in her own writing, and for many that knew her, is perfection.”

Like any unattainable absolute, perfection melds with opposing ideas: chaos, desolation. Martin stoked such contradictions, sending strange impressions of herself and her artwork into the world like coins that still spin beyond the grasp of biographers and critics. But for those New Mexicans who knew her in the last decades of her life, the interplay between Martin’s exacting practice and her vibrant, late-blooming social life held its own exquisite internal logic.

Collective Solitude

“Asceticism is a mistake / sought out suffering is a mistake,” wrote Martin not long after her post-New York road trip, which swooped around North America (including her birth nation of Canada) starting in 1967 and ending in New Mexico in 1968, where she’d previously held a teaching post at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque.

As Nancy Princenthal chronicles in her biography Agnes Martin: Her Life and Art (2015), the journey wasn’t as lonely as Martin later described it. It included a two-week hangout with the sculptor Lenore Tawney, a friend and likely lover from her New York years, through Big Sur and Flagstaff and fabulous Las Vegas.

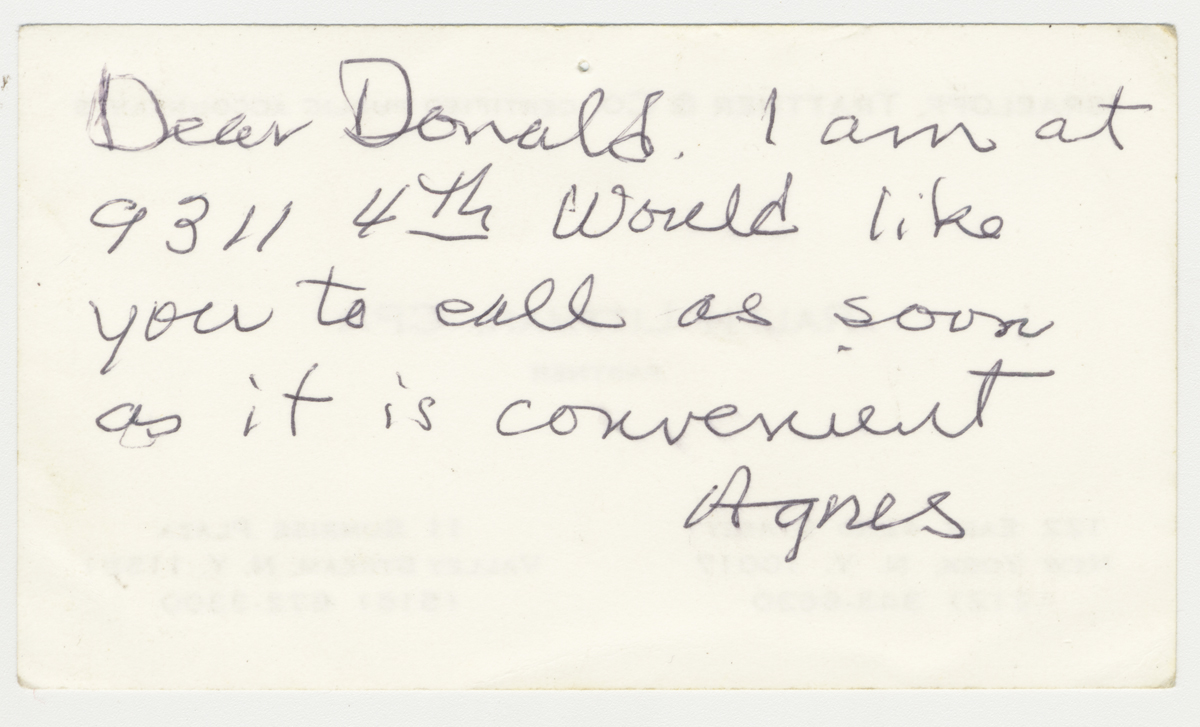

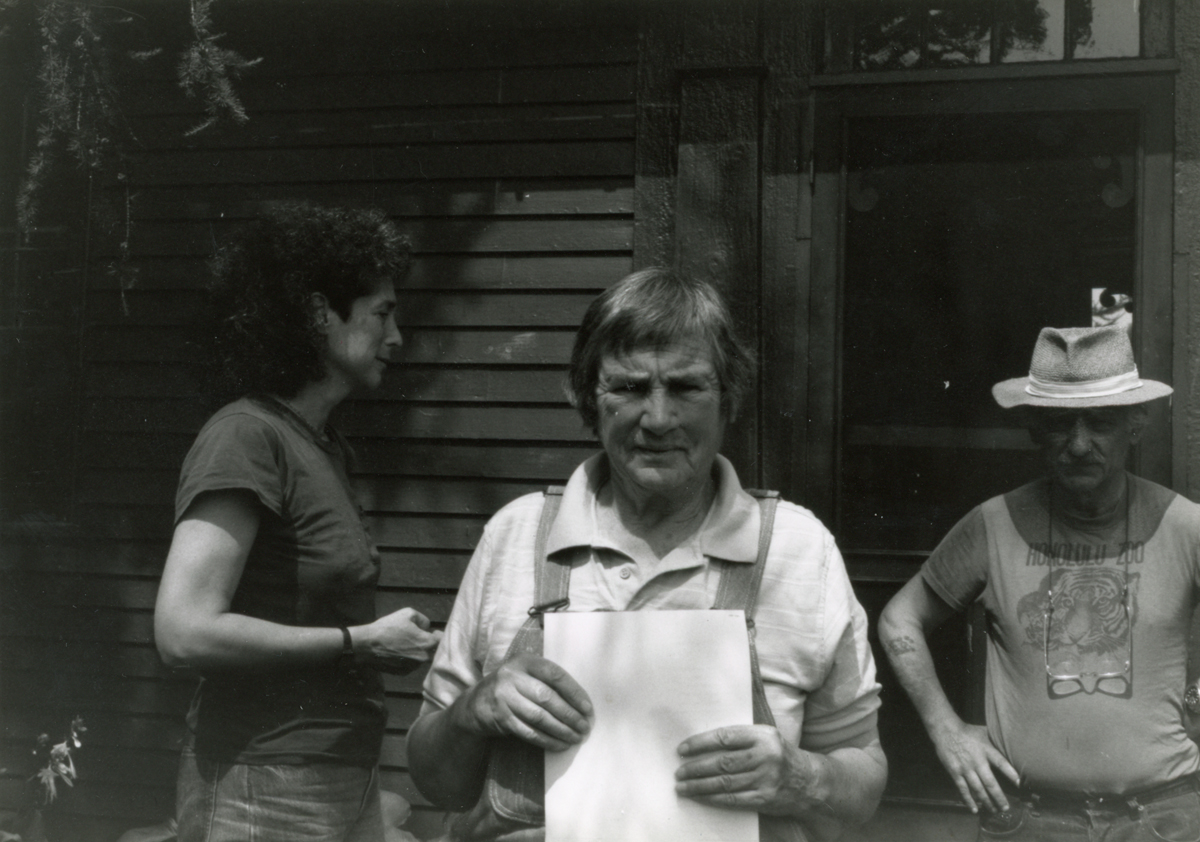

Martin embarked on her most punishing adventure years later, but again sought companionship in it. Following her time in Cuba, she moved to Galisteo, New Mexico, which is a short drive from Santa Fe, to live on the property of a young photographer named Donald Woodman (who would later marry the artist Judy Chicago). In 1978, when Martin was sixty-six, the duo cruised the Mackenzie River in the Northwest Territories of Canada, near her hometown of Saskatchewan.

“[It] was one of those things that sounds like an interesting trip—‘Wow, let’s do it,’” says Woodman. “Not thinking about: Oh, we’re going over the edge of civilization here.” They traveled in a janky motorboat, following a course plotted by the voices in Martin’s head. Her schizophrenia, which was diagnosed in her forties and helped drive her from New York, was waxing. They experienced moments of true mortal danger on the journey, but also stopped at a Chinese restaurant and the movies.

When you paint, you don’t have time to get involved with people, everything must fall before work.

“She was always under the voices, she could never escape them,” Woodman says of this time in Martin’s life. Later, he examined some of her earlier compositions featuring fluid scribbles and tallies, as she was transitioning away from biomorphic abstraction and toward the straight lines of her mature style. “I realized: the lines weren’t just lines. You could interpret them as writing—as a way of getting control over the story in her head.”

Woodman’s ethereal photography from the voyage (a glittering ice field, a portrait of Martin peering out at a far shore) seems to converse with Martin’s work and build another thesis: that her glowing abstractions, which increasingly incorporated horizontal bands, are distilled from nature. Martin vocally took issue with both concepts—her art as communication system, or organic reflection—instead emphasizing the “purely retinal and sensual prospects” of her marks, as Princenthal puts it.

Martin’s enlisting of Woodman, which echoes other tense-but-steadfast attachments throughout her life, likewise conjures a more relational portrait than she might have preferred. In her New York days, during which she mostly resided in the queer art enclave of Coenties Slip, Martin spoke about the necessary push-and-pull of living with other artists—a dynamic that Peiffer labels “collective solitude” in The Slip.

“Painters must live together because other social contracts are barred to them,” Martin told a reporter from Cue in 1958. “When you paint, you don’t have time to get involved with people, everything must fall before work.”

Queen Bee

Woodman lived with Martin for seven years, at the end of which she purchased his Galisteo property. She lived there for fifteen years in all, an era of intense productivity and new conviviality. Martin forged links with a growing array of wayward art-star neighbors including curator and scholar Lucy Lippard, and artists Bruce Nauman, Susan Rothenberg, and Harmony Hammond.

“In Lippard’s words, by the end of the eighties, Martin had become ‘a real queen bee,’” writes Princenthal. Hammond recalls that she loved parties (although never danced), and there are conflicting reports of her favorite drink: “Martin-is” or sherry. Princenthal notes, “Increasingly over the years, Hammond recalls, younger women artists came to Martin on ‘pilgrimages,’ to pay homage.”

I didn’t know there were a lot of other people… I thought she was just talking to me.

One of those artists was Susan York, who caught one of Martin’s legendary lectures, mailed her a show announcement, and then picked up the phone. The Santa Fe–based sculptor says, “I called that first day, and she was like, ‘Come for tea. Tea at three.’ And then every time I’d come—‘Come again.’ So I did.” They lunched for years, and Martin would visit her at the Zen center where she lived at the time. She’d also show York new works, leaving her “gobsmacked.”

“There was such a generosity with her… she showed me what her life as an artist was,” says York. In the spirit of “collective solitude,” such friendships seem to have been siloed: York was surprised to hear about Martin’s other connections. “I didn’t know there were a lot of other people… I thought she was just talking to me. Obviously, a lot of other—probably women—artists.”

Martin’s most intense and poignant mentorship was likely with Karen Yank, a Wisconsin-born sculptor who met Martin in 1987 when the latter was a faculty artist at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine. “She was like the sage of the summer… she’d say something so simple and then leave, and everyone would just gasp,” Yank says. She remembers a particular critique from Martin that “cut through my soul”—they just understood each other.

Back in New Mexico, where Yank had recently moved, they met every Wednesday or Sunday in Galisteo. Martin introduced Yank to her method for emptying the mind and allowing imagery to flow into the void. “I would meditate—start five minutes a day, added and added… a good ten years I struggled with it,” Yank says.

Martin and Yank’s artworks are currently paired in the exhibition Abstracting Nature, on view through October 12 at Albuquerque Museum. At the start of the show, one of Martin’s stripe paintings is framed by a free-standing Yank sculpture: a two-toned disc of welded steel with a square cutout.

You are going to have a baby girl. I had a vision. Stop worrying. It’s fate.

Their bodies of work engage in an aesthetic wrestling match of sorts: Martin’s horizontal lines versus Yank’s verticals, Yank’s metallic scribbles against Martin’s crisp lines on canvas. Yank recalls “analyzing [our differences] to death” with Martin, but feeling certain of their common subjects: “energy and excitement and happiness and joy.”

Yank meets me at the exhibition with her twenty-something daughter Alix, who was another ambivalent force in their relationship. Martin had initially opposed the idea of Yank getting married, but bonded with her husband-to-be and came to approve. But motherhood was a step too far—Martin wanted her to stay focused on her artwork.

“She said, ‘You’ve made such headway—not now,’” Yank recalls, but she was approaching forty and seriously considering it. “A couple months later, I came up to see her in Taos, and she said… ‘I’m giving you the BMW to keep the baby safe.’ I said, ‘I’m not even pregnant.’ And she said, ‘You are going to have a baby girl. I had a vision. Stop worrying. It’s fate.’”

Grandma Agnes

Martin dubbed herself Grandma Agnes, and allowed Yank’s daughter unfettered access to her studio. “She said, ‘Let her touch my materials, touch my paintings,” says Yank. “At one point Alix went up and kissed [a] painting, and Agnes was overjoyed.”

In Martin’s Taos years, Yank vividly remembers her physical vigor (especially for someone who “never ate vegetables”) and her congeniality with other elders at the nursing home. That was when Yank “saw her really open up… she could be around more people instead of just one-on-one.” Yank recalls a particularly decadent picnic with Martin, and she often socialized with another young family: Abiquiú-based artist Richard Tuttle, poet Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, and their baby daughter, Martha.

“I experienced her complete transformation,” says Yank. “I started with her when she was very much about isolation… and [by the time] she was on her deathbed, there were all of these messages on my landline: ‘Agnes wants to see the baby.’” Martin died of congestive heart failure in 2004, at ninety-two years old.

She contradicted herself often, seeming to enjoy how this continually unraveled any narrative thread about her life.

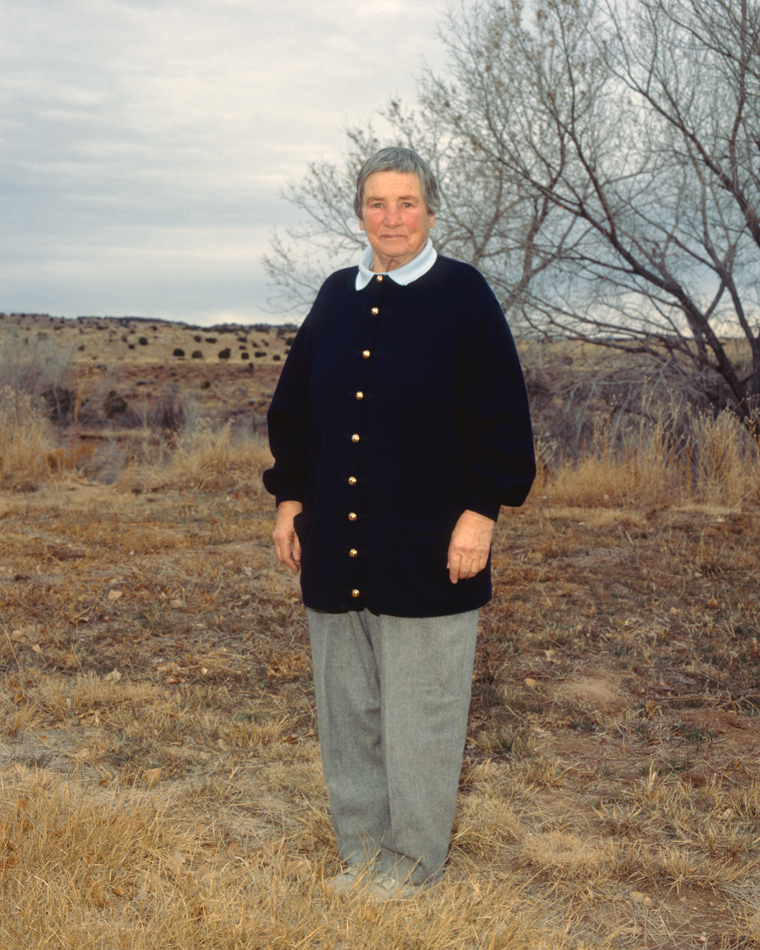

Like her contemporary Georgia O’Keeffe, Martin’s desert tenure was an artistic retreat that doubled as a tightly controlled project of 20th-century self-iconography. But unlike O’Keeffe, who engaged famous photographers to portray her as a crisp, monolithic form against New Mexico’s wide-open skies, Martin trafficked in mirage-like autobiographical diversion.

“She contradicted herself often, seeming to enjoy how this continually unraveled any narrative thread about her life,” writes Peiffer. One portrait from Martin’s later years somehow intensifies and lays bare all of the incongruity. Taos-based photographer Paul O’Connor captured Martin in her studio in 1996 for his ongoing photo series Taos Portraits. (Disclosure: I contributed an essay to his 2024 book Taos Portraits II and received a copy in return.)

The photograph is a tight closeup of Martin’s wrinkled face and glistening eyes, her expression telegraphing a vast and ambiguous arc of emotion. O’Connor recounts the precise moment: “She just very matter-of-factly said, ‘You know, I haven’t always been this overweight.’ And I understood that as a crop decision, so I quickly switched lenses and came right up to her face… and she loved it.”

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this piece stated that Agnes Martin was sixty during her Mackenzie River voyage in 1978. She was sixty-six.