I have been wracking my brain, trying to render seductive the idea of photographic prints made with macerated spinach. Bear with me.

First, let us establish: I have long been a hypocrite when it comes to the use of art materials. In my civilian life, I collect rainwater and ration showers. I rinse baggies and hang them to dry. I sort recycling with stalwart vigilance that irritates my family. But, in artist mode, if I have film to wash, all conservation-impassioned bets are off.

I consider the closet and basement darkrooms I have made over the years, the chemicals washed into city sewers on several continents. Paper (mountains of paper!), bleach, animal-derived gelatin coating acetate surfaces, planned (or condoned) obsolescence of machines, chemicals leaching from lithium batteries, the cooling of terabytes of data in massive banks, rare-earth metals in chips. Here in the New Mexico desert, I cringe at one student’s solitary print swirling in its final wash: twenty minutes of running water down the drain. Neither digital nor analog practice can claim moral high ground; both rely on an extractive and industrial production that is increasingly untenable. I ask, what is the artist’s role in an age of imminent breakdown? Must I shut that water off?

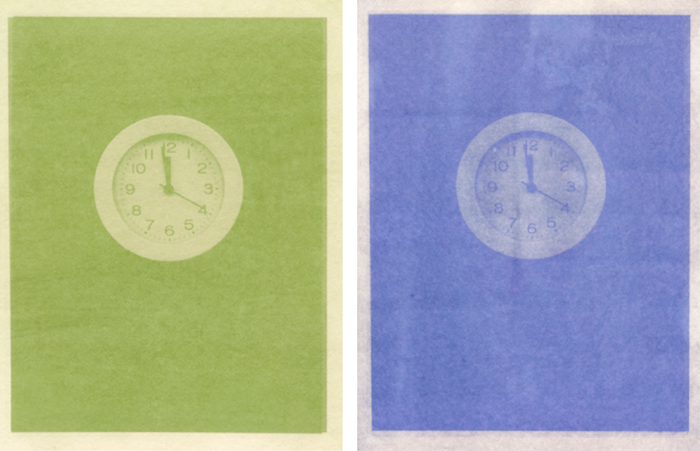

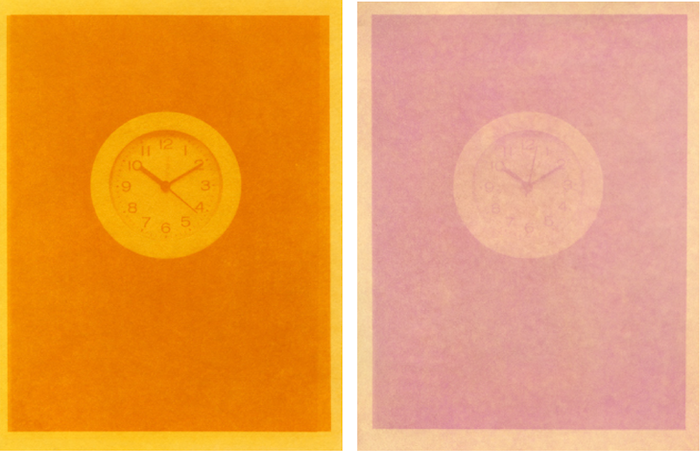

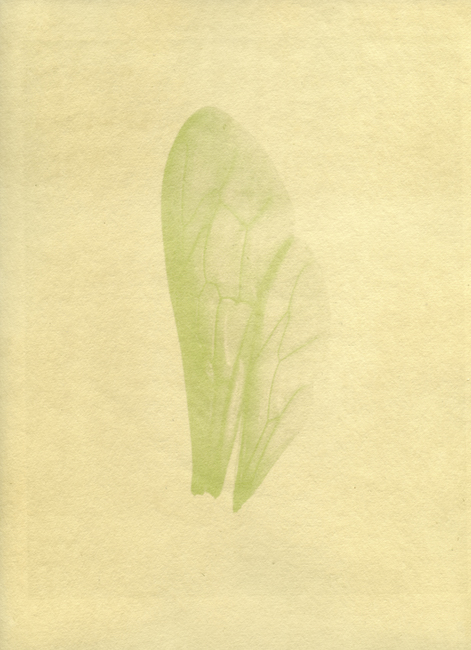

In the scope of the history of photography, the anthotype (flower print) figures as little more than a footnote with a metaphorical pat on the head (endearing, though unlikely to mature!). Plant materials form the emulsions for this crude printing method: berries, petals, or leaves are crushed or pulverized to stain paper. Exposed through transparencies or objects, sunlight slowly bleaches an image into existence on the dyed substrate. The anthotype is both impossible to standardize for commercial distribution and unfixable—two death knells for general embrace. And a third: protracted exposure times—days, weeks, months—make it impractical for most of the medium’s needs, as they have come to be understood.

As they have come to be understood. Our relationship to photography itself, to both the instantaneity of capture and any presumption of permanence, may need to change as we hover on the precipice of environmental catastrophe. Could the humble anthotype represent our future (gentle, fugitive) experience of photography?

Perhaps I have been reading too many novels set in dystopian futures. A collapsed grid is a common plot conceit; the fettering of industrial photographic practice would be inevitable. In repetitive applications of spinach mush, I imagine that I practice for these futures. I nurture seedlings intended for photographic paper-coating pleasure. I forage lichens that might hide lurid color potential. I move wooden contact frames around the yard, chasing oblique rays of sun. A successful print, pulled from its frame after months baking in the desert sun, is both a jolt of pleasure and, perhaps, a vital recalibration of my time-based medium of choice. Can we remake a culture of photography that places more value on the act of making itself, and on more ephemeral, less commodified prints? Do we have time?