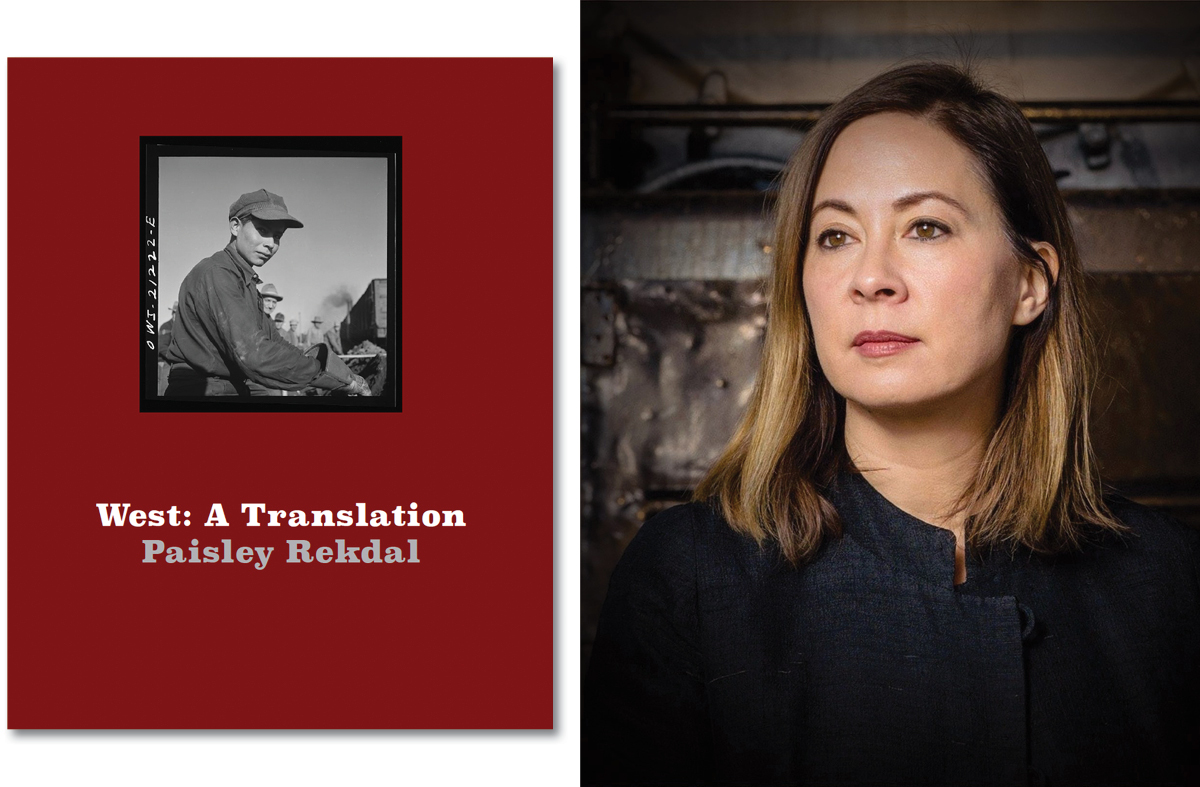

Salt Lake City–based writer Paisley Rekdal discusses poetry as an archive and cultural connecter in the history of the transcontinental railroad.

Paisley Rekdal, who served as Utah’s Poet Laureate from 2017 to 2021, is the author of seven books of poetry, two essay collections, and a hybrid memoir. Her latest poetry book, West: A Translation, which was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2023 and longlisted for the National Book Award, imagines the untold stories of transcontinental railroad workers. A culmination of extensive research, West investigates absence to reveal a shared humanity and surprising cultural connections. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Readers can engage with West: A Translation in book form and through an interactive website made of video poems. How did the website project come about?

When I was given this commission, the first thing I thought about was doing a multimedia performance. I knew there would be images and text together so that people would have a multi-sensory experience. I feel that one of the benefits of a website is that anywhere in the world, someone can access these kinds of stories, these images, and have their own experience with this history. But I also really love the fact that the interactive experience of a website allows readers to take control of their own reading experience.

In a recent Lannan Foundation reading and conversation, you posed the question: what is it that poetry does as an archive? Any thoughts on that?

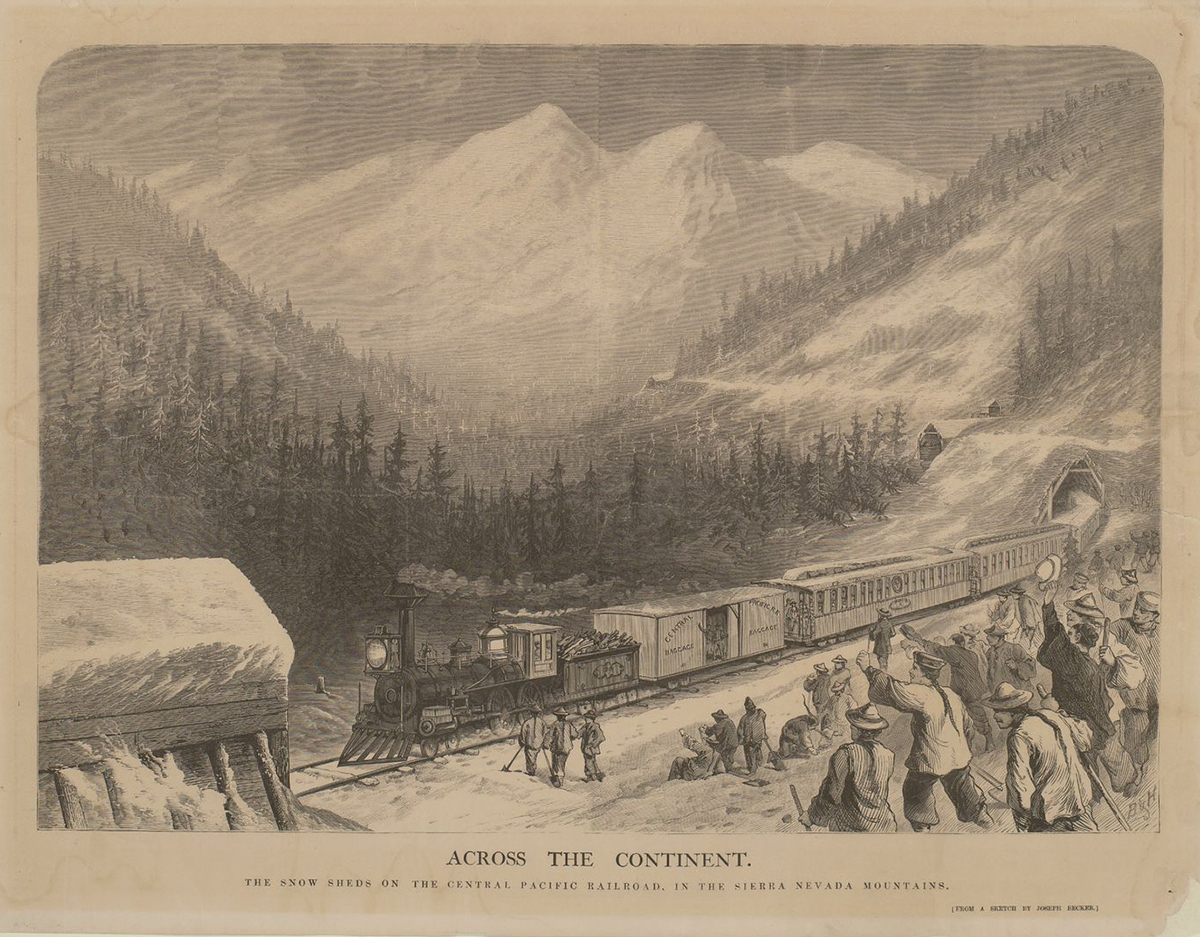

The benefit of poetry as an archive is that it allows us the imaginative space and opportunity to answer what the actual institutional archive refuses to give us. And what I mean by that is if you go into the transcontinental archive and you say, “I want to learn about Chinese workers,” you will find an immediate absence. There are no readers, no diaries, no journals that have been preserved, for whatever reason. The archive as it exists registers only the fact that these men were there and worked on the railroad, but we have absolutely nothing else about them.

Poetry allows us that imaginative space to try and enter as many of these stories as possible. But if you want to do an ethical imagining of the past, I think you have to ask yourself all the time: “Am I writing these poems to please myself in the present moment, or am I writing these poems to actually recapture something that may be slightly beyond me and my own desires about the past?”

That was the biggest concern for me in writing West. I knew I was trying to write a history even as I knew it was going to be a failed history. And I don’t want readers to think, “Oh, this is official history,” but I want people to know this is one way of reading the facts.

What is the most surprising thing you discovered in your research for this book?

I remember in my research I was listening to a conference that had been taped. An African American woman got up in the audience and asked this group of panelists of white transcontinental experts, “What were the relationships between the Chinese and the Native Americans?”

It was a question I had, too. I found out through footnotes, in fact, there were a series of Paiutes and Shoshone tribal members who had either adopted or intermarried with Chinese railroad workers. One of the stories that really haunts me, and I write about it in the book, is a story of one Chinese man who became fluent in Ute and memorized all the stories of the Ute and the Paiute in their own language. When he died, sixty Ute and Paiute elders went to mourn him at the Indian Agent’s office in Cheyenne.

I write in the book it’s startling to me how one culture can carry the memory of another inside it. I think that was the thing that really impressed me about the transcontinental research, finally. Which is that the official archives and records might not contain these stories. But if you go to oral histories and you go to these cultural narratives that are maybe family narratives and private narratives, they keep other people’s stories deeply alive within them. They tell these stories, and they tell their own stories too, to the point where they start to intermix together, and I thought that was so beautiful.