Name: Pablita Velarde

Tewa name: Tse Tsan (Golden Dawn)

Born: Santa Clara Pueblo, September 19, 1918

Died: Albuquerque, January 12, 2006

Known for: Murals and earth paintings depicting Pueblo life

On a survey taken outside a 1993 exhibition of Pablita Velarde’s work at the Wheelwright Museum, one visitor wrote, in awe: “that a woman of her time would be able to find her creative life and explore it until her seventies and be recognized… to know her life and work in all its richness, pain, and joy.” How does any woman in this world, how especially does any woman of color in this world, find her creative life? As a moment for women, this one, November 2018, makes such a feat seem, at least to me, even more incredible, and even more worth celebrating.

Velarde, who became known for making earth paintings, grinding minerals and rocks into pigments using metate y mano, was the first female student to attend class with Dorothy Dunn at the Santa Fe Indian School full time. In school, they experimented with using charcoal for blacks, clay for whites, sand for browns, and reds from La Bajada. Velarde also worked with Pueblo artist Tonita Peña, who became her mentor and encouraged her to pursue painting as a profession, which was then considered by her Pueblo to be a masculine pursuit. At the time, only male artists were supposed to include living people in their work, roles which both Peña and Velarde worked against. Velarde would go on to use earth pigments from her travels, insisting on using pure colors found in nature instead of mixing colors. As a child, she and her sister had both been blinded by an eye disease, similar to a cataract. Velarde was blind until age four and a half and has said that the experience “helped me more or less pay attention to detail and store it up here so that I’ll never forget.” Her paintings later in her life came to her in what seemed like dreams but were, she insists, “just my memory waking up to something that I hadn’t thought of for a long time.” Her paintings focus on daily Pueblo life with close attention to detail, emphasizing not a vision of an idealized world but a recognition of life and people as they are.

Passionate about her artwork and committed to being self-sufficient, she worked a variety of jobs—a nanny, a switchboard operator—and sold her paintings at the portal of the Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe for a few dollars each.

Velarde painted murals in Houston, Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and at Bandelier National Monument, using her earth pigments, oil, and watercolors. For Bandelier, she was commissioned for a WPA project to paint eighty-four scenes of Pueblo life. The painter was in her twenties when she made these works between 1939 and 1946, and the pieces have been in storage since the forest fire of 2011. Velarde married Herbert Hardin in 1941, and he was soon drafted into World War II. Passionate about her artwork and committed to being self-sufficient, she worked a variety of jobs—a nanny, a switchboard operator—and sold her paintings at the portal of the Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe for a few dollars each. She and her husband separated in 1959, in part because of Hardin’s resentment of Velarde’s fame. Eventually, Velarde was called “the greatest woman artist in the Southwest” by Clara Tanner and won the Ordre des Palmes Académiques (1954) and the New Mexico Governor’s Award (1977).

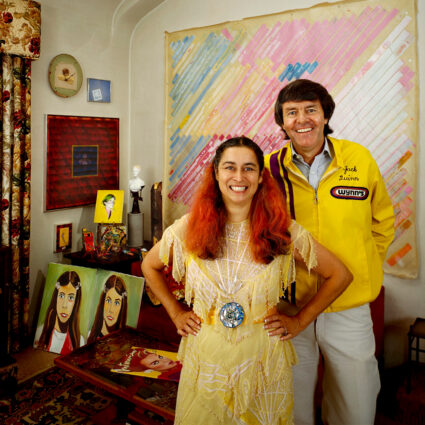

Velarde’s daughter, Helen Hardin, and granddaughter, Margarete Bagshaw, followed in her footsteps to become well-known artists in New Mexico (though Velarde initially discouraged her daughter from pursuing a career in art). While Velarde’s work served to document Pueblo life and record its details, Hardin’s acrylic paintings became increasingly abstract and expressive, rebelling against her mother’s style and a more traditional school of painting. Hardin died in 1984, at age 41, after battling breast cancer. While Helen Hardin broke tradition with her style of paintings, her mother’s fight was to be allowed to paint at all, pushing against gender roles and expectations for women artists in her time. When she was commissioned to paint a mural at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque later in her life, Velarde painted in a self-portrait, breaking with Pueblo painting tradition.