Gutiérrez Hubbell House spotlights life-sustaining New Mexico acequias and reimagines museum practice with a new guest-curator program.

ALBUQUERQUE, NM—You can see a ditch on the east side of the main boulevard that carries you to Gutiérrez Hubbell House in Albuquerque’s South Valley; and, if it’s spring or summer, it’s full of flowing water. It’s a somewhat peculiar sight, though not uncommon in Albuquerque, or much of New Mexico.

These ditches—in New Mexico known as acequias—are part of an intricate network of irrigation canals that divert water from rivers to private residences and farmlands. The acequia system, which came to this region by way of Spanish settlers in the 17th century, is integral to sustaining life in an arid desert climate. The channels allow water to flow to crops and gardens, creating an ecosystem that supports plants, animals, and the people who have stewarded the land, all while passing down traditions, both cultural and life-sustaining, through community.

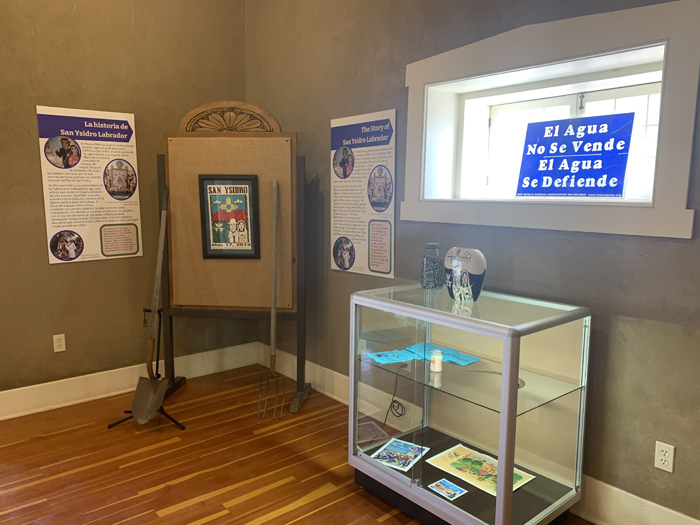

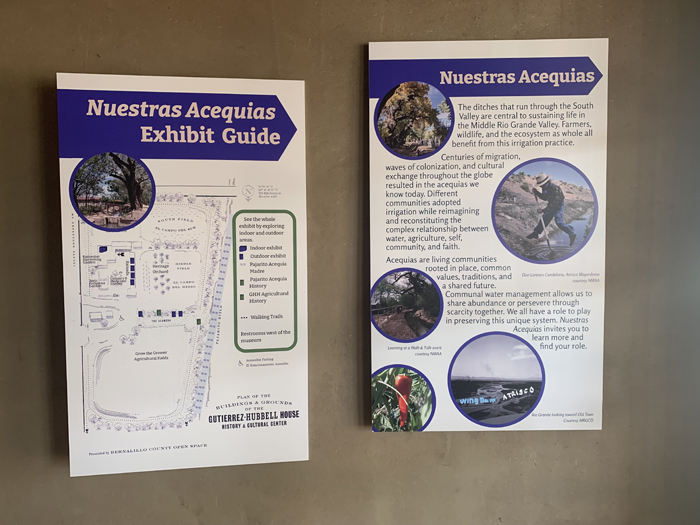

In Albuquerque, community-led and -organized groups continue this tradition of sharing education and knowledge, which is fundamental to sustaining this way of life, especially in a time of outsourced agriculture. This is what inspired Nuestras Acequias: Remembering Our History, Irrigating Our Crops, Nourishing the Future of Our Community. The exhibition at Albuquerque’s historic Gutiérrez Hubbell House—located on a route once known for commerce and cultural exchanges—is the first show in GHH’s pilot guest-curator program that is reimagining how knowledge is produced, circulated, and shared with the public. GHH site manager Elisabeth Stone says the program seeks to provide a container for the community wisdom of acequias that has been honed for centuries in local and regional areas.

The culture around water-sharing began shifting in the 19th century after the United States acquired New Mexico as a territory. Instead of being seen as a resource, water was commodified—the typical custom of U.S. public utilities. While traditional irrigation continued to thrive amid this lifestyle shift, a considerable number of people living on the land were not irrigating their fields and thus not maintaining or learning the complexities of the ditches. Today, the water systems of arroyos and acequias engineered throughout Albuquerque tend to blend into the background—without tending to them every day, season after season, people become accustomed to the vital waterways to the point of nearly forgetting about them, but this is perhaps even more of a reason to celebrate and integrate them into daily life.

Nuestras Acequias—a collaboratively curated exhibition organized by the Center for Social Sustainable Systems, American Friends Service Committee, South Valley Regional Association of Acequias, and Bernalillo County Open Space—brings Albuquerque’s crucial life-sustaining ecosystem front and center, both inside of the museum space and outdoors. Some information is mounted alongside the backdrop of the historic house, but most of the interpretive signs hang along the outdoor portal guiding visitors toward the acequia madre (“mother ditch”) on the property.

The property’s ten acres have been cultivated as farmland thanks to the irrigation of the Pajarito Acequia. Placing most of the information outside of the house, which directs visitors to the Pajarito Acequia, was an intentional decision for the curators and GHH staff because it gives visitors a firsthand experience.

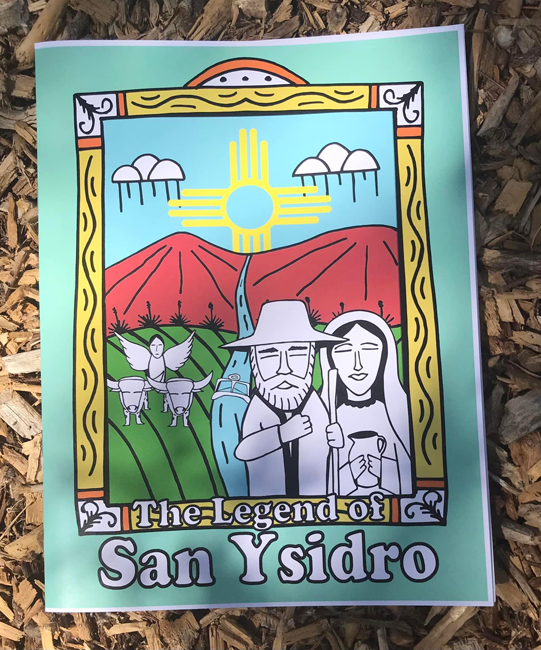

The scope of the exhibition, which closes on July 9, 2022 with a day of walking tours, music, and poetry, discusses the multidimensional nature of acequias, from the historical significance of how the water-sharing system came to New Mexico; to the environmental impact of agricultural cultivation in a desert; and to the cultural influence that the acequias have had on New Mexicans’ way of life for centuries.

A major part of the show that drives these themes is the robust calendar of public programs, which has included panel discussions on water and environmental justice, workshops on rainwater harvesting, acequia walking tours, and community celebration days. Stone explains that the programming is meant to be interdisciplinary and address a wide range of topics to reflect “acequia-based life.”

“If you’re not an irrigator, the acequia is an important factor in your experience of place,” says Stone, referring to how integral the acequias are to everyday life in Albuquerque. Indeed, while the smaller, lateral ditches that irrigate individual properties are on private land, the acequia madres serve as neighborhood walking trails covered in shade from 100-year-old cottonwood trees. A community benefits from the wealth generated by an acequia-irrigated farm, and an individual’s physical and mental health can improve just by living in proximity to an acequia.

Stone says that she wants community members to feel like their knowledge is given the same kind of attention that a large museum institution would offer to conventional scholarship and research. The history of museum practice is mired in problematic methods that involve extracting cultural wisdom and wielding the knowledge as a commodity, separating the culture-ways from the people of that culture. The GHH guest-curator program offers remediation to this exploitative precedent by reaching out to the people and communities who have upheld their own practices and asking them to expound on the wisdom of their lived experiences for the sake of enlightening the general public. When it comes to acequias specifically, this practice is even more valuable as this water-sharing system is unique to this area but is still somewhat obscure, especially to newcomers to the state.

Built in the 1860s, the GHH is a historic landmark that sits on the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, the oldest European roadway on the continent established by Spanish settlers, which is both celebrated because it enabled cultural exchange and criticized as a tool of settler colonialism. The GHH was a private residence until 1977, at which point the upkeep of the property fell to volunteers in the neighborhood. In the mid-1990s, the house, which has also served as a post office and mercantile, was sold to a community organization after a “Save the Hubbell House” campaign. Bernalillo County eventually contracted the committee that rescued the house to create interpretive signage and manage the archives. Today, the property is recognized for its historical value and serves as a cultural institution and education center.

After decades of hyper-local care and maintenance, Stone now oversees the guest-curator program, among other projects, as the first full-time employee of Hubbell House. After Nuestras Acequias, there will be more guest-curated exhibitions, hosted by GHH youth education programs, and an interactive Day of the Dead altar. The museum plans to continue trailblazing this method of public, collaborative knowledge-sharing and setting an example for a new precedent to take shape among cultural institutions.

Nuestras Acequias: Remembering Our History, Irrigating Our Crops, Nourishing the Future of Our Community is scheduled to remain on view through July 9, 2022 at Gutiérrez Hubbell House, 6029 Isleta Boulevard SW in Albuquerque. A closing ceremony will take place Saturday, July 9, 11 am-2 pm.