Three New Mexico–based artists—c marquez, Susan York, and Judy Tuwaletstiwa—reflect on their relationship with the material that has defined their practice.

Material—

“a physical substance or thing that can be made into other things”

Monogamy—

tall tumble mustard

In 2017, c marquez decided to make art with only one material, tall tumble mustard. They intended the commitment to last one year, but eight years later, it continues.

In a 2023 interview with the Taos Abstract Artist Collective, marquez (who uses they/ them pronouns) explained, “When you take everything else away and you work with one material, it feels more open to possibility. To me, it’s almost overwhelming to have every material at my disposal, because it’s hard to make decisions.”

•

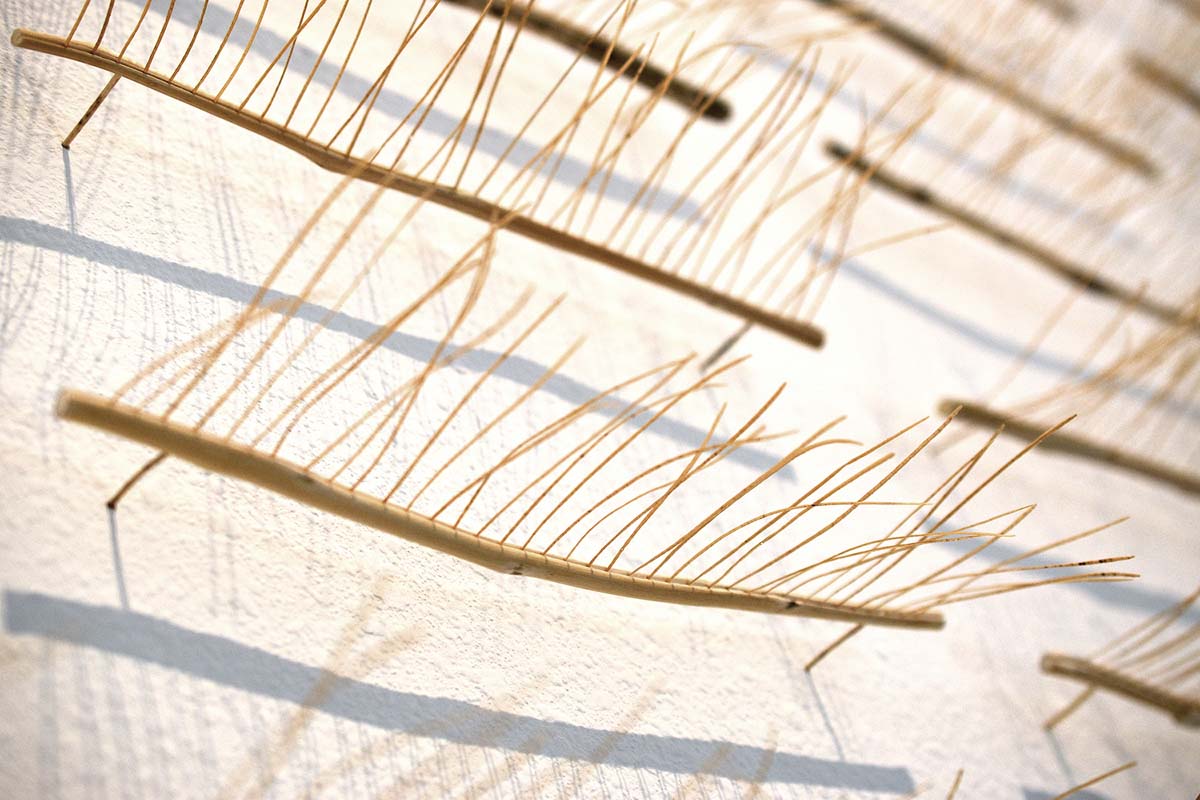

Tall tumble mustard hangs from the ceiling of the artist’s studio in El Prado, New Mexico. I enter the room and immediately tilt my head back to see better. The light from a central skylight gently illuminates the dried plants in its path.

“If you look up here, this color has been out in the seasons longer. The blond, the super blond is fresh. If tall tumble mustard winters outside, it can get grayer, even sometimes black. This is the natural color, you see how it changes?”

They say they know at a glance if a tall tumble mustard, often called tumbleweed in the Southwest, will work for an installation.

“Different projects need different strengths. I can even tell if the plant was not fully developed before it broke off, because then it has a really thin outer wall and isn’t as strong.”

They tell me the crown is the most vulnerable part of tall tumble mustard, the easiest to cut. The plant grows increasingly strong near the root.

•

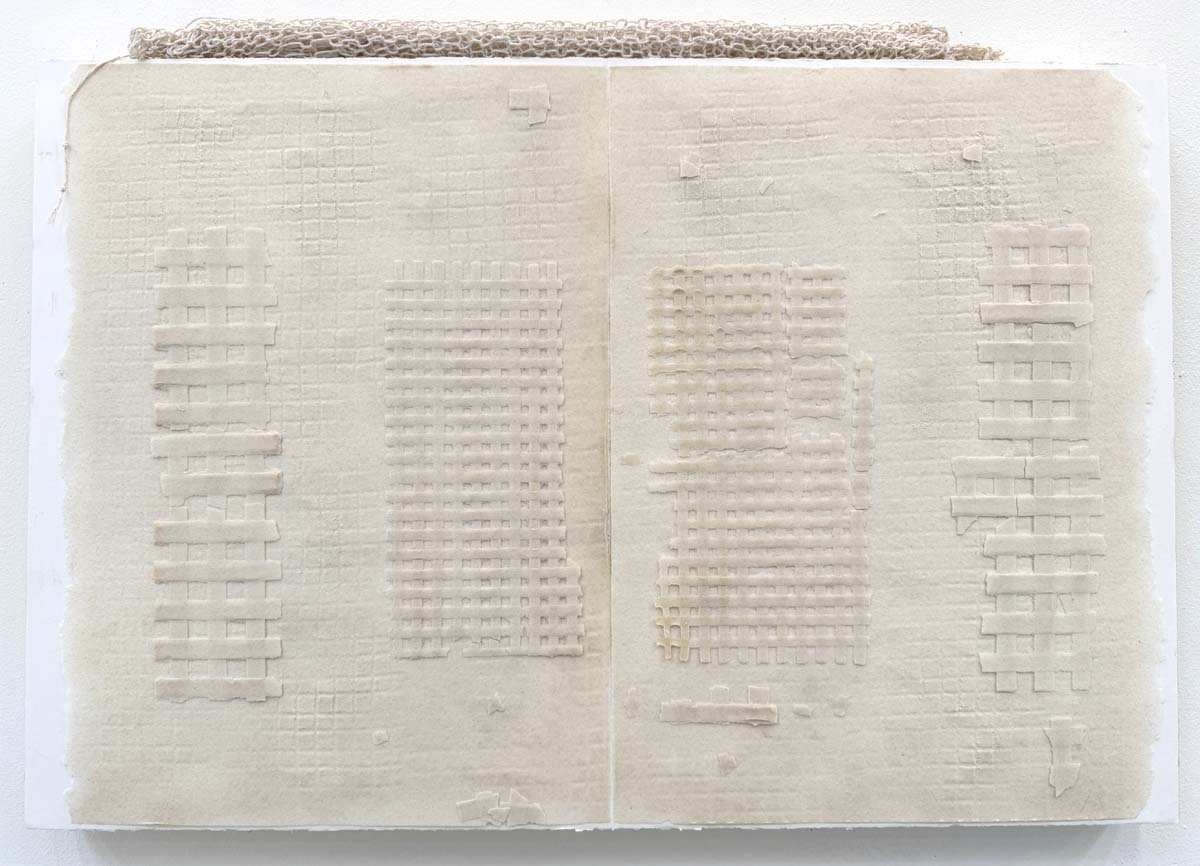

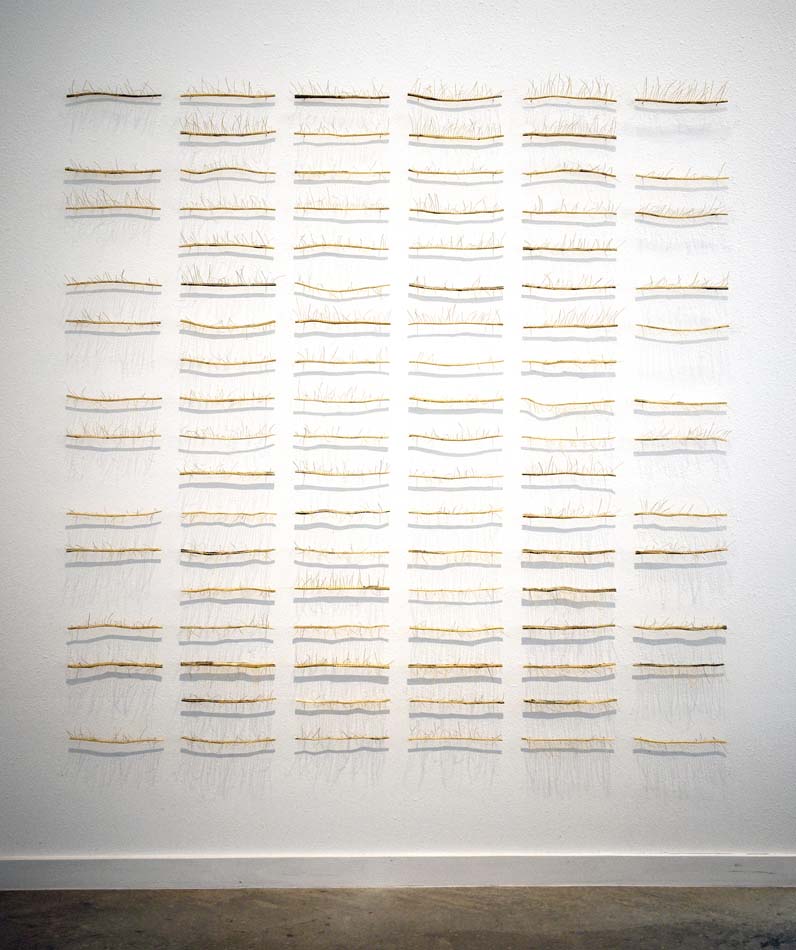

I turn toward a sculpture that hangs opposite the studio desk. In it, horizontal sections of tall tumble mustard hang in a grid. However, unlike a traditional grid, this one includes spaces that intentionally break up the pattern and give the material more room to breathe.

“You see how the plant is. It has a lot of air. I mean, it lives on air. It disperses itself by flying through the breeze. So, the form remains true to the plant.”

I ask the title of the piece. “3653.”

I learn that numerology often distills any group of numbers to a single digit. Later, I notice all of marquez’s titles reduce to eight, which in numerology characterizes a balance between the spiritual and material aspects of life.

•

They like to live with the work, watch it move, fall, age over time. Most of their walls are filled with sculptures or holes from previous sculptures.

On one wall full of delicate forms, they point out the shadows.

“There’s another relationship happening there. They’re not touching, but their shadows are. It’s this sense of… close but no contact.”

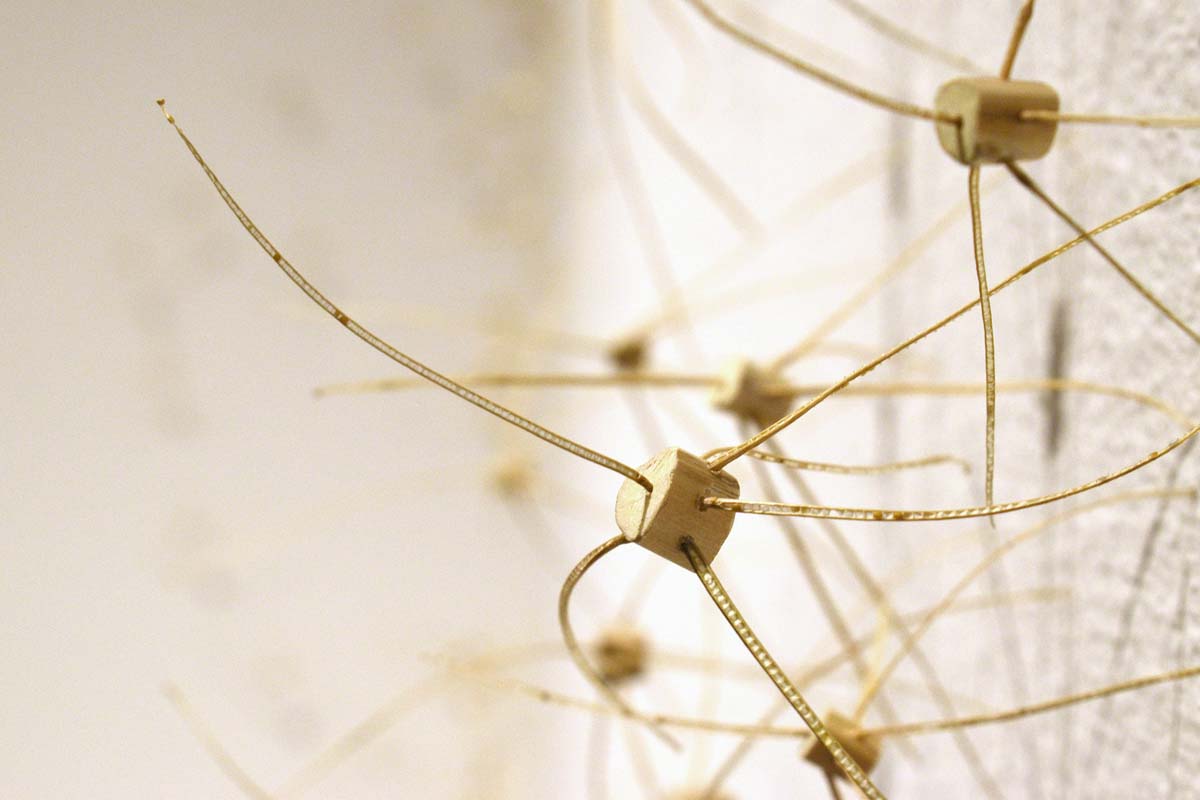

They step forward and reattach a fragile, threadlike leg into the wall.

“I learned it will unravel if you don’t leave enough overlap. When I put them together, I try to make sure these legs don’t come out. The way they’re all inserted, they’re kind of holding each other.”

•

I ask marquez if they think they’ll ever stop working exclusively with tall tumble mustard.

They answer without hesitation.

“Why would I? I love it… there are a lot of meditations where they tell you to think about a being, a person, an animal, something that gives you joy and love, and to allow yourself to feel that feeling. And it’s always this plant. Always.”

graphite

Susan York opens the door of her studio off Siler Road in Santa Fe. As we walk from a room full of equipment to one with a small round table and two chairs, we pass a large ceramics wheel.

“I took ceramics every semester I was at University of New Mexico. I took beginning three times, intermediate three times, advanced three times. Repetition is, I guess, a common denominator in my work.”

She worked in ceramics for over two decades, then began to work with graphite “in the same singular way.”

•

York shows me a few sculptures she is in the process of polishing and refining. The varying shades of gray have surprising depth.

“It’s more like looking at the surface of a pond. This piece needs to get polished, but it’s easier to see, because there’s a little bit of shine. When you look at a pond you can see into it—it’s not like a painted wall that’s opaque and just stops right there.”

I see her examine the surface of the graphite, then slightly nudge the piece to better catch the light.

•

We walk over to a framed graphite drawing. I raise my arms to take a photo and York tucks both her hands gently into her pockets.

“It took quite a long time, because when you start with a really small line, you know, every line [that follows] is really narrow. For me, I can’t change it. A line creates a certain kind of presence. You have it that first day, and then some days you almost need to copy it, to maintain the continuity.”

York sometimes draws as many as fifty layers, as she did in this piece, to convey the density and luminosity of graphite. I follow the lines from left to right, tracing the movement of her hands over time, deliberate line by deliberate line.

In the drawing, white and black are separated by a liminal space. The gradient reminds me of dust that has not (and will not) settle, of how what’s past sometimes lingers in the air.

•

Near the end of The Unfolding Center (2014), York’s collaboration with poet Arthur Sze, she notes:

[I work] by layering on, layering on, and layering, and then rubbing away, so that the paper falls off, and then layering, and layering, and layering. So there’s this constant dance between the material and the material falling away.

glass

In Glass (2016), Judy Tuwaletstiwa writes,

This is a book about glass.

It is also a book about finding my way to glass,

a medium that synthesizes concepts

that I have explored, over the past forty-five years, in fiber, paint, and writing.

As I turn each page, I think of the breadth of that movement—from fiber to paint, paint to writing, writing to glass.

•

I follow Tuwaletstiwa’s written directions to her home and art studio in Galisteo. A large dog follows my heels with his head low. Tall grass bends in several directions.

Tuwaletstiwa is sweeping as I walk in, so I look around for a moment while she puts away the broom.

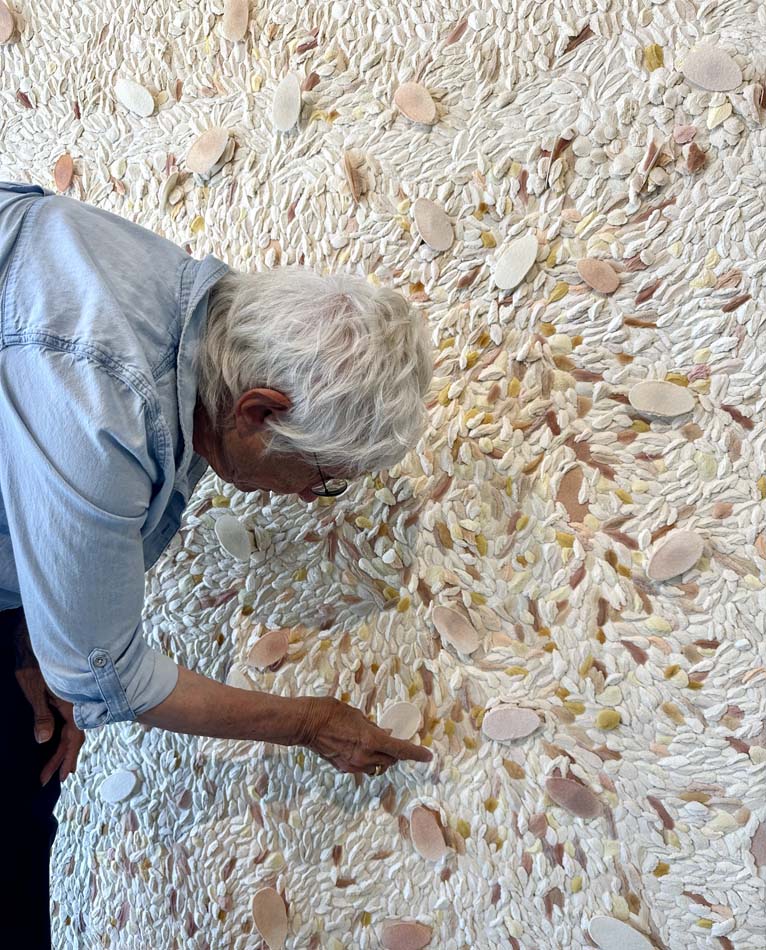

On the wall next to my shoulder, I notice a set of five panels composed of thousands of small irregular oval fragments. The colors vary from moss green to pale blue. The texture is like a fine powder with subtle indentations. At first, I assume the pieces are made of fiber, but as I lean in closer, I realize they are glass.

Around the corner I see several color tests pinned to the wall. On one of the sheets, she has written a quick note to herself, “Work with the brokenness to see what happens. Do not refine.”

•

We sit in chairs under one of several generous skylights, near a red and black triptych propped against a wall. The outer sections mirror each other, but the center is unique.

Tuwaletstiwa follows my eyes.

“I lifted a two-by-four-foot piece of glass out of a kiln, and it broke. So I just kept breaking the glass, and it became something [that] would never have been if I had applied it directly.”

The fragments resemble thin shards of paper charred by fire. I think about the conditions that cause sand or rock to take this form.

Glass always begins as something else.

•

I comment that her practice seems to be in dialogue with her material, each adapting to the characteristics of the other.

Tuwaletstiwa nods graciously, but pauses.

“Glass is an amorphous solid. It’s always moving, even if we can’t see it.”

I ask what it’s like to interact with a material that is always moving.

“When I was a kid and I spent the night at my grandma’s house, I would get up to go to the bathroom at night. There was a long hallway and it’d be dark. We didn’t have night lights then, and I’d lift my arms out in front of me. To walk in the dark that way… this is what it feels like.”