From a courtroom to the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Native artists Mateo Romero and Jason Garcia are correcting the records.

A Pueblo elder talked about how she thought about the people of a neighboring Pueblo throughout the day as they celebrated their Feast Day with a Corn Dance. From her village, she looked across to the feasting Pueblo as monsoon clouds released at the end of the day. She celebrated from afar, thinking to herself, “Oh, my goodness, those Cochitis are believing; they danced and they were so intense about their faith that the rains would come, that indeed, the rains did come.” Rains that would nourish not only their own village, but every community in its path.

This anecdote encapsulates Pueblo belief about the interconnectedness of all living things, with the landscape not just representing beauty, but being tied to a larger worldview, one that is centered on the cause and effect of human action on the natural world; in this case, the dancers and singers encouraged the clouds to bring the rain.1

This interconnectedness is something that Cochiti Pueblo artist Mateo Romero thinks about when painting landscapes and other sites. When talking about his Okhua (“cloud” in Tewa) series, he references water-related symbols depicted throughout traditional Cochiti pottery—pots are adorned with cloud, water, and lightning motifs; animal figurines depict frogs and other moisture-loving animals; and vessels are designed to hold water. Romero’s grandmother, Teresita Chavez Romero, was a potter in the mid-to-late twentieth century, and her pottery, like those of other Cochiti potters, reflects the blessing of moisture for a people engaged in subsistence agriculture in the arid Southwest.

P’osuwaegeh Owingeh (Water Gathering Place)/Pojoaque Pueblo, the site where three rivers meet, is where Romero lives with his wife, potter Melissa Talachy, and their children; he has a studio at the pueblo’s cultural center. While Romero grew up in Berkeley, California, his father, Santiago Romero, made sure that he and his brother visited his home, the Keresan-speaking village of Koo-ghe’-te’ (People from the Mountains to the North)/Cochiti whenever possible. After undergraduate studies at Dartmouth College, he received an MFA in printmaking from the University of New Mexico. He taught at the Institute of American Indian Arts for a few years.

In 1992, Romero was one of several plaintiffs (including Native rights advocate Suzan Shown Harjo) to petition the repeal of the trademark of Washington, D.C.’s professional football team, whose name was a racial slur against Native people. Although dismissed due to a technicality, this lawsuit laid the groundwork that compelled the team to change their name and logo in 2020. When asked by the Santa Fe New Mexican about this victory, Romero stated that “art is a tool for activism.” Some of Romero’s earliest artworks depict this activism.

Romero says, “Hopefully, there’s a little bit of education involved” when viewers encounter his artworks and their titles, prompting Natives and non-Natives alike to ask, “Why is this the title? What does this mean?”

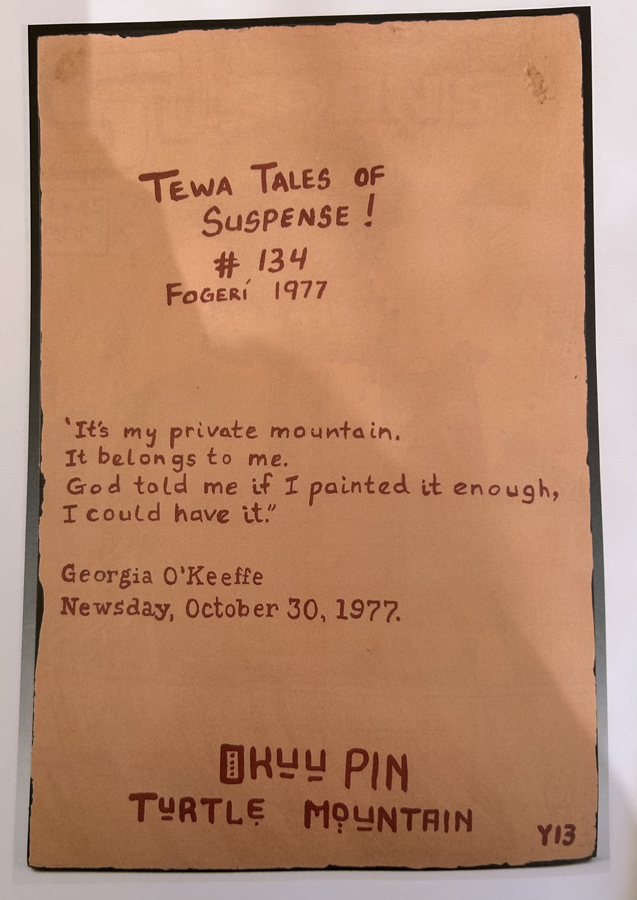

He continues, “I think you [can] take the language of the enemy [landscape painting], and you [can] subvert it. You can use the original Indigenous names… and you [can] talk about Pueblo values. I’m not looking at [the landscape] as some white tourist out here. I’m actually hiking these spaces, taking notes, talking to [Pueblo elders], finding out what the original names are.”

I’m not looking at [the landscape] as some white tourist out here. I’m actually hiking these spaces, taking notes, talking to [Pueblo elders].

An upcoming exhibition at Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country, explores similar concepts of place and identity—more specifically how the outside world routinely associates the Northern New Mexico landscape that O’Keeffe painted with the artist herself, referring to the area as “O’Keeffe Country” despite Pueblo presence that long predates her own.

According to Ka’p’o Owingeh (People of the Valley of Wild Roses)/Santa Clara Pueblo featured artist and co-curator Jason Garcia, “Part of the show is talking about the beauty of the landscape, the significance of the landscape, and that we [Tewas] have been here since time immemorial.” He continues, “We have names for all of these places, we are still stewards of those places.”

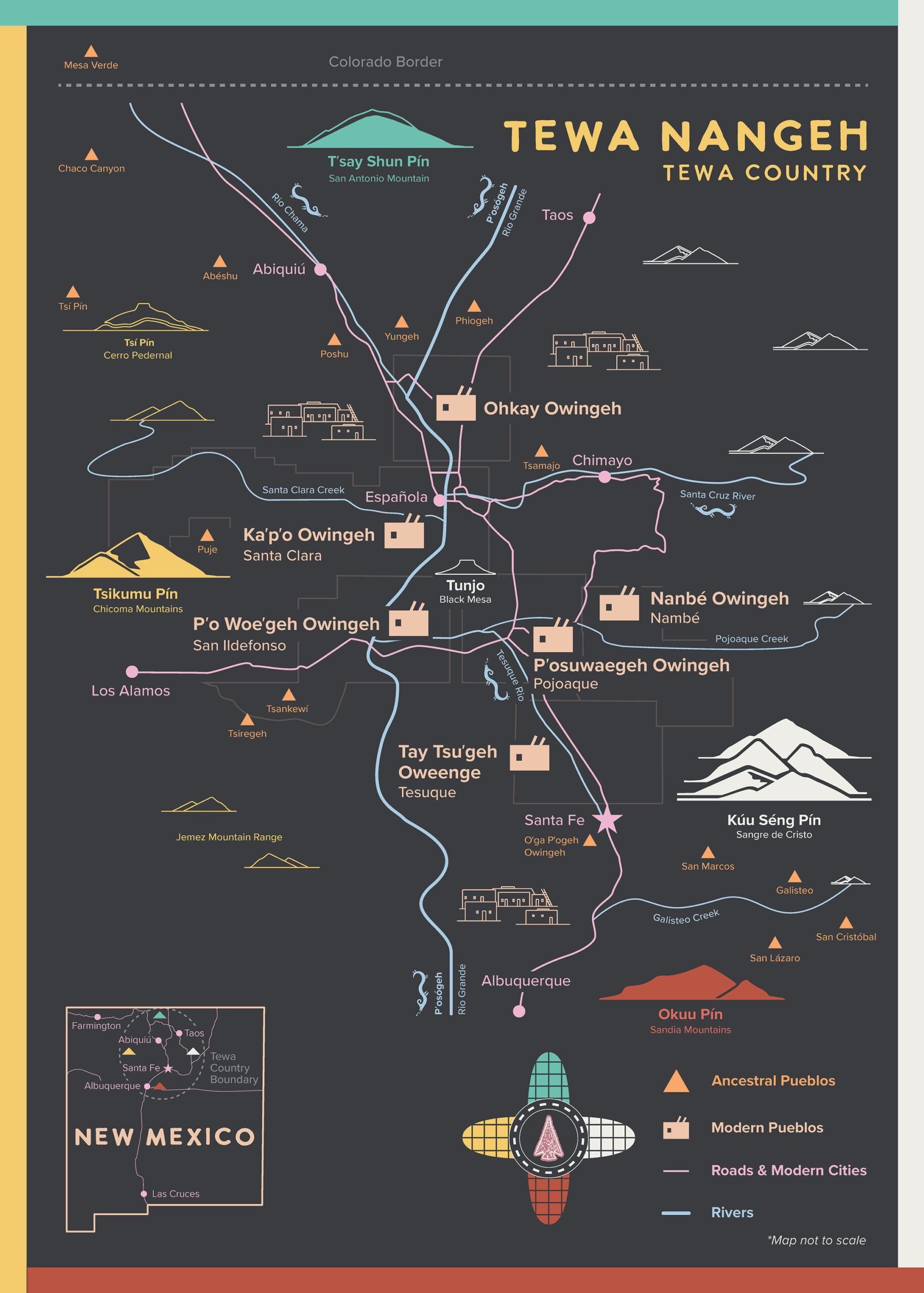

Garcia shows me a working map of Tewa Nangeh that will appear in the exhibition; the four sacred mountains that comprise the boundaries of the Tewa world are prominently identified, along with waterways, modern and ancestral Pueblos, and cities and towns that are now primarily populated by non-Natives. When laid out on a map, it is visually evident that these cities and towns, like Santa Fe and Albuquerque, are sitting on or surrounded by places that have historical and spiritual meaning to Pueblos.

About the use of Tewa in his own work, Garcia says, “It does start a conversation about ‘Why? Who is it for? Do you have any problems [with non-Natives learning Tewa]?’” Garcia explains that he incorporates Tewa words throughout his work with Tewa audiences in mind, remembering attending language classes as a kid; his generation was among the first introduced to formal language learning outside of the home due to disruptions imposed by the U.S. government. He notes how in the past Tewa was so prevalent that it was even used by non-Natives, as a trade language, “Growing up, as a kid, I would often see older Spanish [Hispano] men from the local Spanish [Hispano] villages talking Tewa to my uncles, my grandparents, my dad.”

It’s… subversion as it uses beautiful landscapes to position potentially controversial ideas about Indigenous space

In this era of Indigenous land acknowledgements, non-Natives have become familiar with Indigenous names like O’ga P’ogeh Owingeh (White Shell Water Place)/Santa Fe, which the City of Santa Fe and other institutions utilize on certain occasions in acknowledgement of the city’s Tewa origins and ongoing presence of Pueblo people from multiple villages.

Continued use of Indigenous place names reflect the inherent sovereignty of Pueblo communities to remain rooted in teachings that reflect their own history and culture. According to Romero, “It’s an extension of semantic sovereignty [the use of language to create Indigenous empowerment]. [I’m] using Tewa names to reclaim colonized spaces. It’s also subversion as it uses beautiful landscapes to position potentially controversial ideas about Indigenous space.”

Pueblo names appear on the signs and overpasses of well-traveled corridors, and a few villages have readopted official usage of their Indigenous names in place of Spanish-imposed ones, but the presence of Pueblo culture extends beyond name recognition. Whether or not they are aware, non-Pueblos are connected to the Pueblo world; they are showered by those same clouds that bring relief to a parched earth and to a parched people. As Romero puts it, “I don’t do just landscapes. I don’t do like Portland, Oregon–green landscapes with waterfalls. I do specifically, [what] I call those ‘places of power,’ places around here that are associated with the Pueblo world—they’re ruins, they’re certain compositions that I think are engaging [like] cloud compositions. I’m attracted to certain things in this landscape that are the Tewa world, the Keres world, the Pueblo world.”

<

1. Unpublished interview conducted by the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture as part of its Here, Now and Always exhibition.