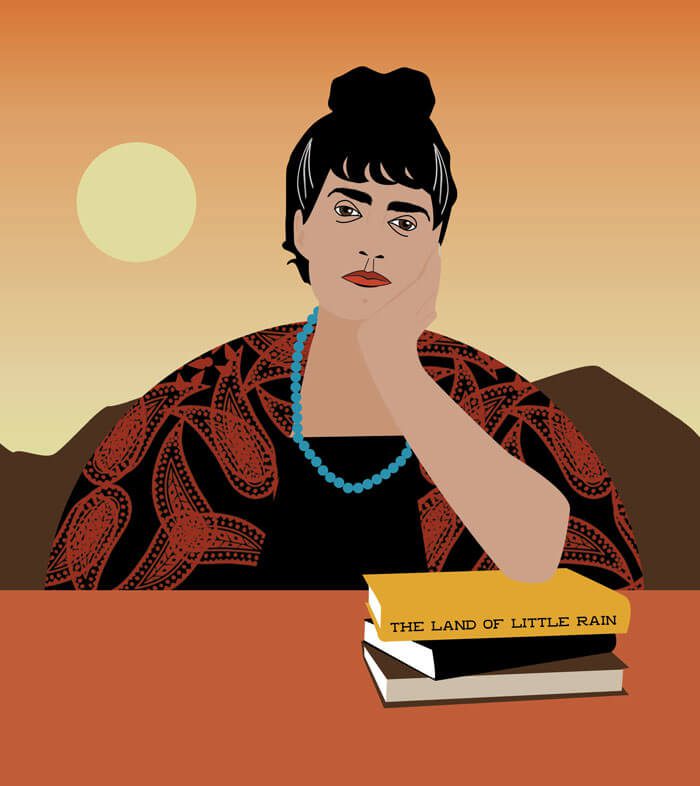

Name: Mary Hunter Austin

Born: 1868, Carlinville, IL

Died: 1934, Santa Fe, NM

Role: Writer, desert enthusiast, founder of Santa Fe Playhouse

Quote: “Myths have grown up about me because I have done what I pleased.”

The phrase “Santa Fe women” calls to mind a range of women throughout history, but it is most aggressively saddled with the stories of a set of wealthy white women from the early and mid-twentieth century. These Anglas went “out West” for a number of reasons: illness, divorce, adventure, fresh air, etc. They used their relative freedom and independence to found well-known institutions and galleries, to establish artists’ and writers’ colonies, to host salons, to harass D.H. Lawrence. Some of them receive an undue amount of attention, by virtue of having held positions of power within a certain elite group of Santa Fe society, and in this column I’ve tried not to dwell too much on their set, many of whom already have histories and biographies written about them.

Mary Hunter Austin was one of these Anglas, but her story and her own writings set her apart. She seems to have lived multiple lives: a writer of more than thirty books, including fiction, nonfiction, and poetry; an early environmentalist who battled for land use and water claims in California; a social activist in the 1912 women’s movement, lecturing alongside Emma Goldman and Margaret Sanger; a champion of Native American rights (and, in my view, an occasional appropriator of Native and Hispanic literatures); and the founder of what is today the Santa Fe Playhouse. She cavorted with Isadora Duncan in France. She befriended writers like Sinclair Lewis, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Jack London, and Rebecca West. She served Ansel and Virginia Adams “a mountain of homemade doughnuts,” later working with Adams on an edition of Taos Pueblo featuring his photos. Willa Cather stayed at her house in Santa Fe, Casa Querida, to finish Death Comes for the Archbishop; Austin later called the book “a calamity to the local culture,” accusing Cather of siding with the Spanish colonists.

As a writer, Austin is best known for her evocations of the desert landscape. Unlike many early Western writers, she saw the earth “not as a repository of resources for household use, but as an undomesticated, potentially feminist space,” writes ecocritic Stacy Alaimo. In the desert, Austin depicted a space in which people might cast off strict gender binaries and expectations, especially the expectations placed on women as mothers and household goddesses. While other conservationists at the time aligned preserving the environment with preservation of the heteronormative nuclear family and the white race—maintain nature to maintain privilege—Austin saw nature as “a place that was not domesticated and that did not domesticate women.” Her story “The Walking Woman” (1903) shows a heroine with “short hair and a man’s boots” who refuses all obligations. “She was the Walking Woman. That was it,” she writes. “She had walked off all sense of society-made values.” This heroine even embraces motherhood outside of marriage. Egads! In her novella, Cactus Thorn (1927), a woman follows her lover to New York, where she discovers that he is engaged to someone else. She murders him, then retreats alone back to the desert where they’d met, utterly anonymous. (It wasn’t published until 1988, having been deemed too “radical” by editors for decades.)

In the desert, Austin depicted a space in which people might cast off strict gender binaries and expectations, especially the expectations placed on women as mothers and household goddesses.

Austin’s “Beloved House” on Camino del Monte Sol at one time housed Chiaroscuro Gallery. Her local legacy includes the city’s first civic theater, the Santa Fe Little Theater, which exists today as the Santa Fe Playhouse, and the Santuario de Chimayo, which she and architect John Gaw Meem helped preserve with the Spanish Colonial Arts Society. You can also see Helen Hunt (!) star in a 1989 adaptation of Austin’s essay collection, The Land of Little Rain, for the PBS American Playhouse series.

To read more about Austin’s feminist environmentalism, see Stacy Alaimo’s “The Undomesticated Nature of Feminism,” Studies in American Fiction 26.1, 1998, 73-96.