Cuba 52

There is no order in this hellish landscape: two policemen raise billy clubs against a figure slouched at the foot of a parked police car. One mass of people raises a sign demanding a strike, Huelga; another yet demands: “Down with the Dictator,” Abajo la Dictadura. Elsewhere, a peasant family stands in front of an ox-pulled cart, their clothing roughly patched, just as US Navy men attempt to climb Havana Vieja’s memorial to José Martí, a Cuban writer who called for the country’s liberation from Spain. Emblems of American capitalism dot the city skyline like highway billboards.

Uncle Sam looms above it all, against the waves of the blood orange sky. He is an oversized puppeteer, pulling the strings of a group of slouching, rifle-wielding men dressed in military uniform. No doubt, Fulgencio Batista, the US-backed military dictator who held power in the country until 1959, is among them. In January of that year, Fidel Castro, a thirty-two year-old revolutionary and lawyer, ousted the conservative Batista in a coup that involved five thousand guerrilla soldiers.

René Mederos created Cuba 52, one of a series of twenty posters published in 1973. He framed the image with words excerpted from one of Castro’s most renowned speeches, “History Will Absolve Me,” recited in 1953. Then only twenty-six years old, Castro spoke for nearly four hours at his own trial after an initial revolt, later memorialized as the July 26 Movement, failed. Speaking of false promises and struggle, Castro called on Cubans to fight for freedom and liberty from Batista’s oppressive regime.

Drawn from both history and Castro’s speech, Mederos’s resulting image captivates, crafting with raw emotion and even anger how the United States had once held an economic grip on the island since the Spanish American War of 1898. Mederos’s series was not the only example of its kind—though it is singular in Cuban visual culture—but one of many thousands commissioned by the Cuban government in the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution. While Castro instituted a new leftist and socialist government, artists all over the country crafted a new aesthetic language for resisting imperialism, in time generating their own “creative revolution,” as the famed art critic Gerardo Mosquera once put it. In fact, Mederos himself was instrumental in this revolution, making a series of Cuban posters supporting Vietnam, for example. That series was eventually exhibited at La Galería de La Raza in San Francisco in 1970. For at least three decades, Mederos’s posters, along with those made by many other artists, became a prime medium of resistance, challenging imperialism, promoting education and economic independence, while also encouraging solidarity with much of the Third World.

From the Public Square to the Archive

When I had the chance to see Mederos’s poster firsthand, I couldn’t help but be reminded of the medium of papel picado, or cut paper. The silhouetted groupings of figures seemed notched from tissue, each collaged together into one vivid and harrowing scene. Cuba 52 lay on a table amongst several other posters hailing from Cuba, haphazardly stacked as I pulled individual examples from large folders to examine with the help of Suzanne Schadl, the curator of Latin American Collections in the Center for Southwest Research (CSWR) at the University of New Mexico Libraries. We were at the basement floor of Zimmerman Library located on UNM’s main campus, standing amongst rows of books and cabinet after cabinet of ephemera. Many of the images we gleaned from the gray shelves were just as stunning as Mederos’s, though stylistically different and much less narrative. There were recurring artists who became readily identifiable by their color palette, whimsical imagery, or style of color-blocking forms. For instance, the artist Eduardo Muñoz Bachs’s innocent and childlike style stood out from the archive. He made some two thousand original movie posters (not all are at UNM) over the course of his life. Many of his works and those of other artists were even signed, proving the artistic value of each example.

Glancing back at Cuba 52, we began talking about the continued relevance of Mederos’s image and, more poignantly, the continued relevance of posters generally. It was evident that the Cuban Revolution had, like other revolutions of the past, generated its own special approach to making the cause accessible to a broad public. It was, as Suzanne described, a key “information format” that helped communicate the multiple socialist initiatives of the Cuban state under Castro to Cubans across the island. Posters also translated ideas—freedom, patriotism, and solidarity—into expressive images that circulated widely in public squares, government buildings, or simply on the streets. For many Cubans, posters were a form of art that took the place of traditional media like painting and sculpture. And what better way to communicate than through print, a medium tailor-made for the masses? Cuba’s poster program pushed ideologies, yes, but it also promoted art as one important weapon in the revolutionary toolbox. With strong graphic elements and rich coloring, these posters aided in the country’s continued efforts toward radical self-determination. The format, more importantly, left galleries and museums behind.

What’s more surprising is that the posters are pieces of yet another puzzle, that of a lesser-known Cuban history.

Talking with Suzanne, I found out that the Sam L. Slick Collection of Latin American, Caribbean, and Iberian Political Ephemera, along with the Jane Norling and Lenora Davis Collection, which contain the materials from Cuba, as well a wide range of materials from other Latin American countries, totals around sixteen thousand. These, along with the entire archive of the Taller de Gráfica Popular (a print workshop established during the Mexican Revolution) make the CSWR one of the foremost repositories of Latin American ephemera in the entire United States.

As the story goes, Slick, a professor of Foreign Languages and Literatures at the University of Southern Mississippi, tasked his students, colleagues, and contacts in Latin American countries with tracking down and collecting whatever posters they could find on their travels. And they did; the archive now covers thirty years of Latin American history, stretching from 1970 to 2000. More than that, it stands as a “people’s archive,” or “a lot of different individuals’ piece of a puzzle,” that contributed in an essential way to Slick’s grander vision. This unconventional way of collecting accounts for the differences in material, and the spectrum of countries that are represented, but also for the quality of each poster. Some examples look almost new, as if hot off the press. Others have jagged edges and cuts in their corners from being stapled to—and then ripped from—a surface. Others have paste on their backs. After some negotiation, UNM acquired Slick’s collection in 2001, though even with sixteen years in hindsight, it’s still difficult to characterize what it actually yields, given the breadth of places and themes the materials covered.

The Cuban posters have seen more attention than most of the archive. In fact, Cuban material has been featured in exhibitions, catalogues, and academic writings. Even The New York Times featured an article about Cuba’s history of producing political posters. Slate, too, published an article about Mederos. Beyond that, it seems only the silhouette of Che Guevara gets much play in the popular consciousness. Yet, the scope of Cuba’s output of political propaganda is staggering. What’s more surprising is that the posters are pieces of yet another puzzle, that of a lesser-known Cuban history. If we here in the United States have inherited flattened accounts of the island, which portray it as simply a communist country that readily aligned itself with the Soviet Union, the posters tell an altogether different story.

Solidaridad

The tense thirteen days that marked the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 created a chain reaction of events that eventually led to the US embargo of Cuba. Cuba, it seemed, had made clear that it sided both ideologically and politically with the Soviet Union under Khrushchev. The posters, however, don’t picture Cuba’s political alignment with the Soviet Union’s cause as we might expect. Rather, posters in Cuba communicated the nation’s support of “cultural democracy.” Just as the country founded several national institutes in support of various cultural forms, posters advertised popular avant-garde films (the Cuban government founded the Cuban National Film Institute and was essential to “Third World Cinema”), bolstered literacy campaigns, and advocated sugar production.

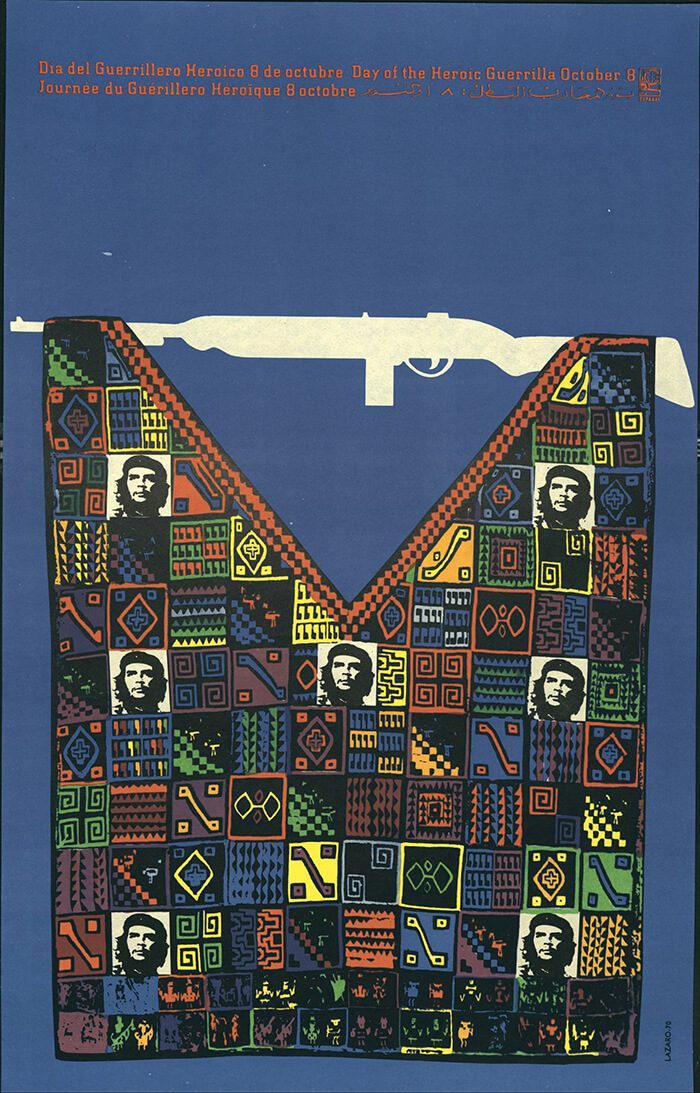

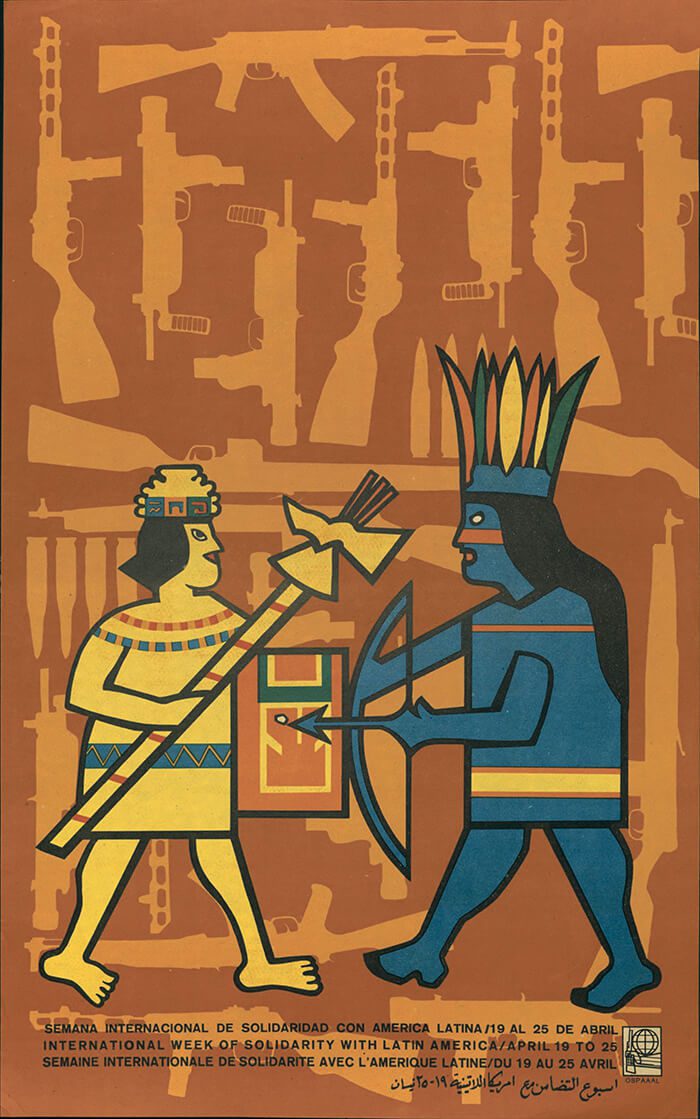

On the last point, Cuba was virtually a one-crop economy, relying on the Soviet Union as their greatest importer. But, as far as the arts were concerned, Cuba couldn’t be more different from the Soviet Union. As the noted art historian of Latin America, the late David Craven, put it, the enemies of the Revolution were “capitalists and imperialists and not abstract art.” While the Soviet Union pressed on with its mode of socialist realism, Cuba’s artists embarked on a far more experimental aesthetic indebted to the New Left. More than that, Cuban posters were undeniably part of Pop art’s origin story, embracing rich color palettes, silhouette forms, and combinations of newsprint techniques with far more abstract designs and methods of visual double entendre. Here, images of pencils might morph into trees, or rifles might double as the patterns of a textile. The posters, moreover, almost always employed the method of silk screening.

How posters conveyed their message was important, then, for if artists readily moved away from any type of realism, they did so as a way of conveying another message about international politics: solidarity with the rest of Latin America and the Third World. In fact, the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa, and Latin America (OSPAAAL), first established in Havana, created a web of countries with mutual commitments toward eradicating oppression. Mederos created posters that supported Vietnam, while other posters showed Cuba’s support of independence movements in Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Guatemala, to name only a few. I even came upon a poster in the archive that depicted the muzzle of a black panther; the image demonstrated that, through OSPAAAL, Cuba supported the Black Panther movement in the United States.

Against a lapis-colored ground, the garment hangs from the body of a rifle.

It became clear that OSPAAAL’s stunning spectrum of posters visualized how countries and movements saw themselves and their own struggles in relation to one another. Symbols from multiple places often collided in these posters in this web of connectivity. For instance, one poster loops the image of a Peruvian poncho, replete with geometric stepped designs in an overall checkered format (Che’s face can be seen within the tiny squares), into the language of solidarity. Against a lapis-colored ground, the garment hangs from the body of a rifle. This was only one way of visualizing solidarity, and when I saw it, I immediately thought about how picturing alliance in Latin America meant picturing a precolonial textile technique, perhaps the most abstract of all aesthetic forms. It celebrated October 8, the “Day of the Heroic Guerrilla,” and no doubt, Indigeneity. Elsewhere, posters featured images of Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically elected president of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Others included several languages: Spanish, French, English, and Farsi.

One thing that I wondered about was the role of women. Suzanne noted that there were a number of noted revolutionary women celebrated in posters, but as makers, women were few and far between. While the Cuban government sought to fight imperialist oppression, it still had some strides to make in offering paths for women to enter into print collectives. All in all, the archive revealed both the lapses and strengths of Cuba’s poster movement.

La Lucha Sigue

The US presidential election was still fresh in many Americans’ minds when media throughout the country and world urgently reported the death of the defiant Castro. He was ninety at the time. That day, November 25, brought both celebration and grief, a flood of mixed emotions over a leader who, through American eyes, had become synonymous with the Soviet Bloc. It seemed that Castro was, moreover, a dictator of another, very far off time. He seemed to have lost his political edge, and some of his reputation, after reports aired of his own human rights abuses and the realities of economic decline after the Soviet Union fell. His regime, too, became oppressive for many. Now the embargo has been lifted, opening up a potentially new chapter in US-Cuba relations, though even that is uncertain.

When looking at Mederos’s poster, the time doesn’t really seem so far off. Pointing to the police car and the officers brutalizing a kneeling man, I said that image looked like it portrayed our American present. Suzanne replied that it seemed as if our country “was moving backwards in time.” Though the posters came to be in a much different place and era, they still speak time and again to some ongoing realities in the United States, from police brutality and the waging of unfounded wars, to the destructive nature of classism and racism. Because posters have a special power for distilling complex histories and current realities to broad publics, they take on a much greater role than just propaganda. They are forms of cultural processing, images and words that help us both deal with and communicate discontent. And so, with and through them, la lucha siempre sigue, the fight always continues.