Jiyoun Lee-Lodge of Salt Lake City grapples with themes of isolation and belonging—in comic book-style works influenced by Korean folk art—in her ongoing Waterman series.

SALT LAKE CITY—Invariably, each of us has encountered the acute vulnerability accompanying loss, a life transition, or perhaps self-doubt. One’s identity may falter when pulled apart from the comforts of routine and home, rendering us a stranger among our fellow humans.

For Jiyoun Lee-Lodge, this feeling of isolation—amid both drastic and seemingly ordinary episodes of transition—have become the impetus behind much of her art.

The Korea-born artist, who had previously resided in enormous cities like Seoul and New York, experienced a monumental life shift when she relocated to Utah in 2018. The move also became a catalyst for a years-long deep-dive into the themes of loneliness and belonging, investigations that amplified in intensity and scope during the COVID-19 pandemic. The latest iteration of Lee-Lodge’s deeply detailed and personal Waterman series—rendered in an instantly recognizable, comic-book style that takes influence from Korean folk art—can currently be seen at Granary Arts in Ephraim, Utah.

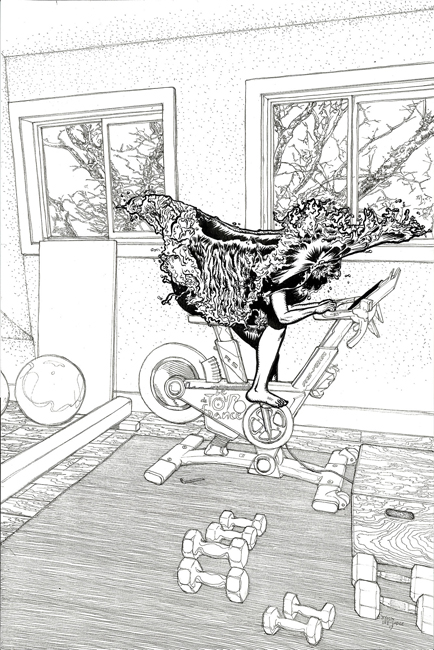

I met Lee-Lodge in 2019 shortly after her move to Utah, and was captivated by her Waterman series, which she exhibited at the now defunct Alice Gallery in downtown Salt Lake City. This spellbinding collection of digital prints features human figures whose forms are engulfed in water and reside in settings such as Utah forests and domestic interiors.

Rippling waves radiate out from the figure, whose human characteristics are evident from the limbs that manage to peak out from the dizzying water. The intricate detail of these works is heightened by the fact that they are devoid of color, sketched in sharp black outlines against pristine white backgrounds.

Lee-Lodge refers to these figures, an ongoing character in her work, as the Waterman. After moving to Utah for family reasons, the artist envisioned the Waterman as an embodiment of her fear of the unknown, with the water symbolizing the familiarity associated with her time living on the peninsulas of Korea and Manhattan. Lee-Lodge—who maintains training in both traditional studio art and animation, which she utilized in her work as a concept artist while living in New York from 2006 to 2017—carved out a studio space in her new home and began sketching as a way of navigating her major life changes.

“[The sketches] were a way I started documenting my fear… the reason I picked that character was that I was missing the open water of my former homes,” says Lee-Lodge. “There was something missing [in Utah] so I began seeing myself as open water. I, as the water, became a missing element in Utah, something alien and vulnerable.”

Broadly speaking, her symbolic use of the Waterman as “the other” parallels Utah’s dearth of diversity while also serving as a highly personal manifestation of the artist’s own attempt to navigate her new reality. Further, Lee-Lodge selected compositions of nature and domestic scenes as a projection of her insecurity and desire to belong.

“These are places that I want to live, for example having a nice house, or places to hike and ski, as an aspiration,” she says. “These are places I felt pressure to try and fit in. Placing the Waterman in these locations was projecting myself as a failing person in these locations.”

But then something remarkable happened. Exhibiting the series in Salt Lake City gave the warm and engaging Lee-Lodge—who regularly supports her fellow artists at gallery openings—an opportunity to speak with many people who related to sentiments of isolation or feeling like a stranger in their own cities.

She talked with LGTBQ youth shunned by their conservative families as well as locals who felt that they didn’t fit into the religious or highly outdoorsy stereotypes promulgated as the ideal Utah identity. While Utah still has a notable diversity problem, these conversations helped Lee-Lodge relate to her new home and forge connections with people for whom her work really resonated.

The Waterman series, as a result of her conversations, diverged from a monochromatic palette into bold-colored works where isolated figures were placed in domestic interiors. Waterman: Changing, which debuted at Salt Lake City’s Utah Museum of Contemporary Art’s Exit Gallery in the summer of 2021, grappled, at a critical juncture, with a collective transition between coronavirus precautions and a strong desire to resume so-called “normal life.”

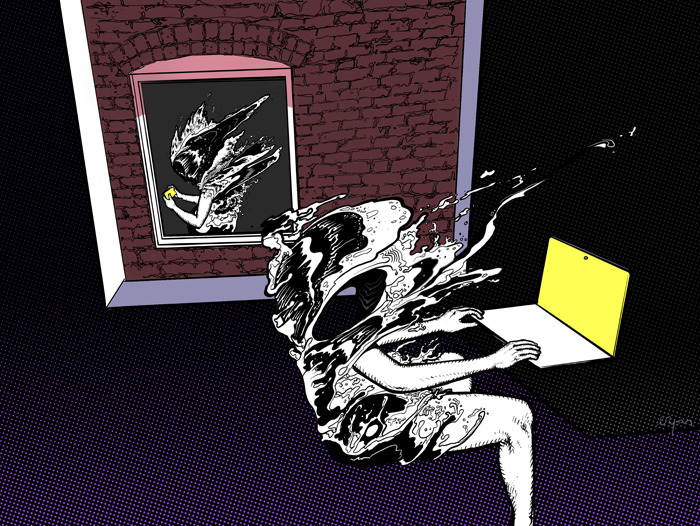

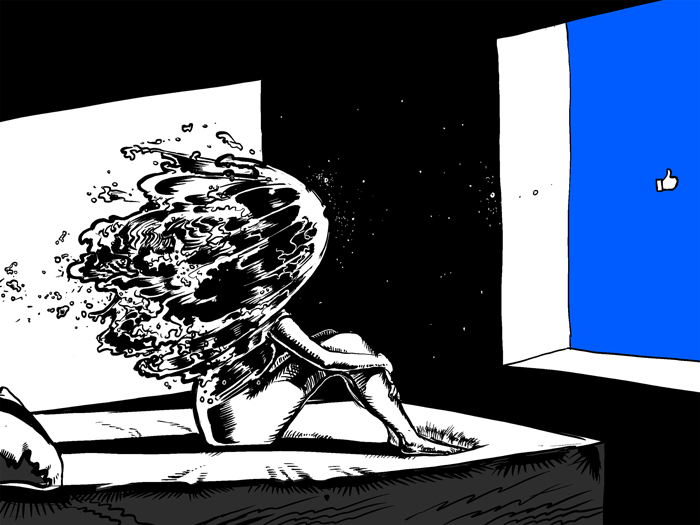

The series wrestles with the role of social media and technology in fomenting our isolation. Taking influence from Edward Hopper, Lee-Lodge places her signature Waterman character alone in various interior settings.

In Waterman-Awakening #2 (2021), a figure whose torso and face are obscured by a tidal wave, sits atop a bed, clutching her knees and gazing out a window, consisting of a bright blue screen and the Facebook thumbs-up like symbol at its center. In another work, which she exhibited in her 2021 show Waterman Merging at the Bountiful Davis Art Center in Bountiful, Utah, two figures are seen in their respective rooms staring at screens and seemingly oblivious to the other human’s existence mere yards away, a statement about the intentional modes of isolation that surround us in the social media era.

“This is questioning what we perceive as reality,” she says. “I am asking about the reality of the inside of the little window you have in your hands.”

Of course, Lee-Lodge is by no means the first artist to articulate this willful isolation principle. In addition to Hopper, her work recalls a century-old trope grappling with technology’s disruptive forces. The work of German Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, for one, recalls a horror and condemnation of the modern condition ahead of the First World War, with Street, Berlin (1913) capturing the hustle of the modern metropolis that leaves its inhabitants feeling even more isolated than ever. To Kirchner, the hope and promise of the modern metropolis as a unifying force was a folly. Lodge’s work achieves something similar, an isolation of the source of our alienation, which at once carried such promise of uniting us.

Over the past year, her work aims to investigate the ways we project misunderstandings onto each other. This and other works appear in the exhibition Waterman: Coloring the Stranger, which is on view at Granary Arts in Ephraim through May 5, 2023. This series, taken partly from work exhibited in a group show at Modern West Fine Art in Salt Lake City, as well as work made in the years before, is decidedly more colorful than her original Waterman series.

She cites the 1998 film Pleasantville as a particular inspiration for the series, specifically how the film’s subjects evolve from black and white to color vis-à-vis The Wizard of Oz as they begin to accept emotions and love.

“I saw this as a poetic projection of how we begin to adjust to a particular place, of warming up,” Lee-Lodge says. “Also, as a painter, I missed using color. This series is admitting that I may still be failing at transitioning to the new place on my own, but I have now accepted that this struggle is a part of life, and perhaps will always be there.”

Many think pieces penned during and after the pandemic chart the increasing loneliness afflicting American society. And while virtually all of us will encounter such episodes of transition, art that encourages a discussion on these topics, at once personal and universal, is encouraging, an invitation to remain open to communication in an ever-changing world.