Las Vegas artist Jeannie Hua conceptually illustrates the Tonopah tailings burial site and asks the viewer to ponder the historic neglect of Asian Americans who settled in the American West.

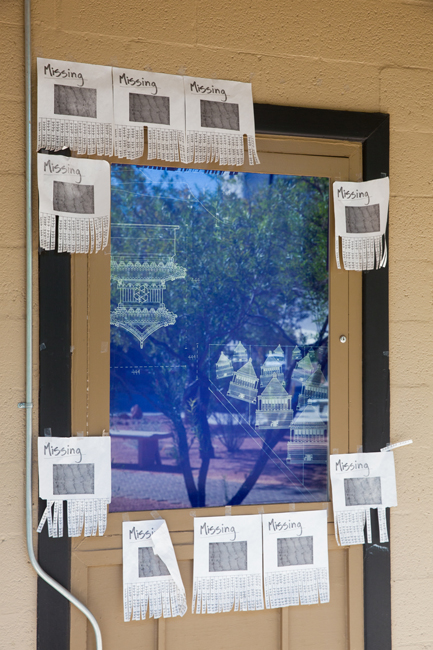

An artwork reflecting on the plight of Chinese Americans who contributed to the formation of the Southwest is on view at the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art in Las Vegas, which has commissioned local artist Jeannie Hua to create the work Tailings (on view until March 16, 2024) for an exhibition on the exterior of the museum building on the University of Nevada, Las Vegas campus. The work focuses on the burial of Chinese Americans under tailings—mounds of mining waste—in Tonopah, Nevada, during the 19th century as silver mining prompted an influx of white and non-white immigrants to settle in the region.

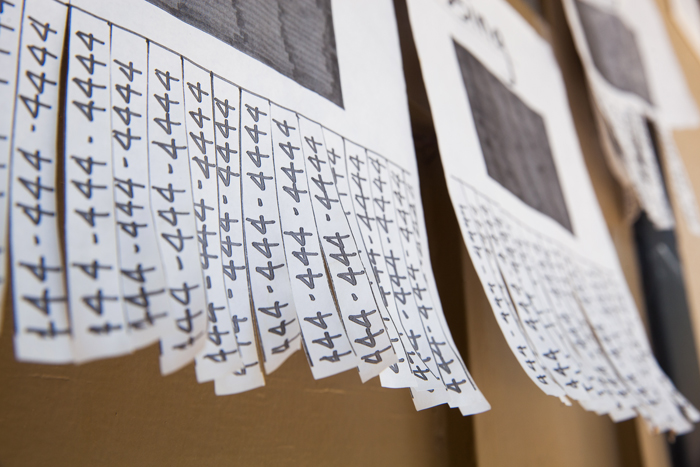

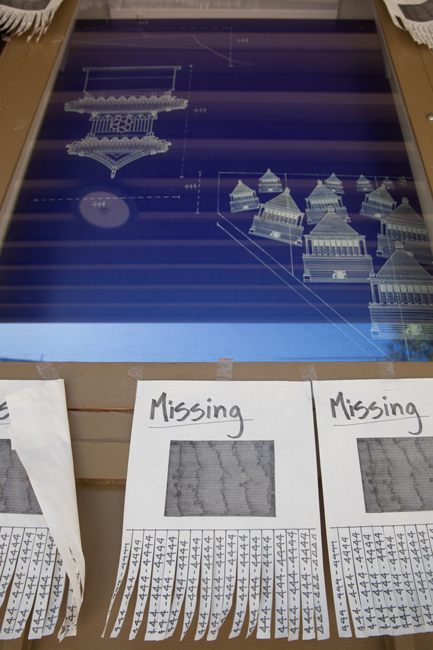

The work takes the form of an architectural blueprint that conceptually illustrates the tailings site. On the left, there is a hill that represents the mound of tailings; the Chinese mausoleum is a reflection of the mound. On the right, there is a fence; within the fence, there are multiple mausoleums arranged in a heap. The work is surrounded by flyers for the missing people buried at the site, showing the telephone number 444-444-444, an allusion to the word for “death” in Chinese.

“When you have a gravestone to mark the passing of someone significant to you, but that gravestone is surrounded by so many others, the significance of individual lives is diminished by the multitude of loss,” Hua says. “The overall design shows borders, lines, delineations, and boundaries—all to segregate what is to be revered and what is to be forgotten and disregarded.”

The project originates from Hua’s thesis exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, where she sought to examine what constitutes a “real American,” exploring the role of Chinese Americans during the Civil War. She found that some Americans of European descent legitimized their American heritage through having ancestors who fought in the war, noting that Chinese Americans nationwide also fought on both sides of the conflict.

Throughout her research, Hua found that there was a predominant “refusal to recognize that Chinese Americans are as much part of the American landscape as Europeans.” After the show, she continued her research, narrowing her scope to the role of Chinese Americans in the development of Nevada, identifying Tonopah as a significant harbinger for the erasure of Chinese American history.

The work poses challenging allegations, as most of the information regarding the burial site is anecdotal.

“The whole town knows about it, but it’s not properly documented anywhere,” Hua says. “When I visited the site of the mining waste, the Tonopah residents were matter-of-fact about what happened. Their attitude was that it happened, and we had nothing to do with it.”

She alleges that there is “no incentive” to document the tragedies since the burial site has been used as a commercial dumping site. Chinese Americans were long prohibited from mining in Tonopah and were excluded from official cemeteries. Widespread discrimination prevailed, and a riot in 1903 left several businesses destroyed and one Chinese American business owner dead.

Hua emphasizes that calling the “souls buried under mining waste as Chinese Americans, versus Chinese immigrants, is a political act” that aims to raise awareness around the historical presence of these communities. In addition, the work honors “not just the disrespected bodies in Tonopah, but also the other yellow, brown, and Black bodies buried outside of cemeteries under the American sky.”